Legend to legend: Don Prudhomme on Don Garlits, Indy, and other great takes

It’s one thing for people like me and you to idolize Don Garlits. Hell, he’s “Big Daddy,” an icon whom we all admire, respect, and love for all he’s brought to our sport.

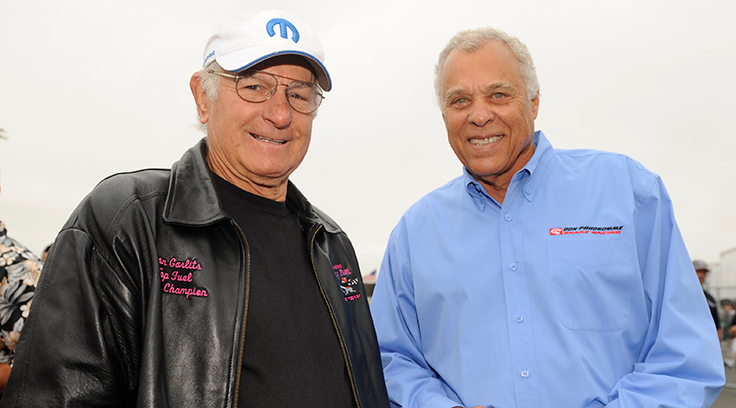

However, it’s another thing entirely when one of his fellow legends — one equally used to being lauded and swarmed for autographs — decides to open up about his love for Garlits, and that’s where we are today, on the eve of the season’s biggest race, as fellow fabled racer Don Prudhomme puts on his fanboy hat to heap praise and admiration upon the guy who would sit next to him on drag racing’s Mount Rushmore.

It all started innocently enough a week or so ago. “Snake,” as he sometimes does, called just to say “Hey” and find out what was going on in my life and in the sport. We chatted for about 15 minutes about this and that — about his motorcycle trips to Mexico, an upcoming off-road excursion in Utah, his much-ballyhooed Sonoma take on Maddi Gordon, and such — and hung up.

A few minutes later, he texted me this:

“I gotta tell you, man, if ever I'm gone, I wanna tell you who was the greatest drag racer of all time: Don Garlits. The things he did to change the sport and save lives with the rear-engine car is pretty [fricking] amazing.”

Now, before you think that “Snake” is contemplating mortality and just had to get this on the record in case he keels over tomorrow, know that even at 84 he still gets up early every morning and walks three miles with his dogs at an age when many of his 80-something-year-old contemporaries have trouble getting from the Barcalounger to the bathroom.

Anyways, we texted for almost an hour after that, and the thoughts he was laying down about Garlits were so good that I asked for an extended interview the next day that covered a ton of fertile ground, including his thoughts about the upcoming NHRA U.S. Nationals and what it’s meant to him over these years. It's some rare, wide-open emotion from the notorious cool-as-a-cucumber Prudhomme.

Swamp Rat 14

Obviously, the big topic was Garlits’ revolutionary Swamp Rat 14, the rear-engine car that changed the sport in 1971.

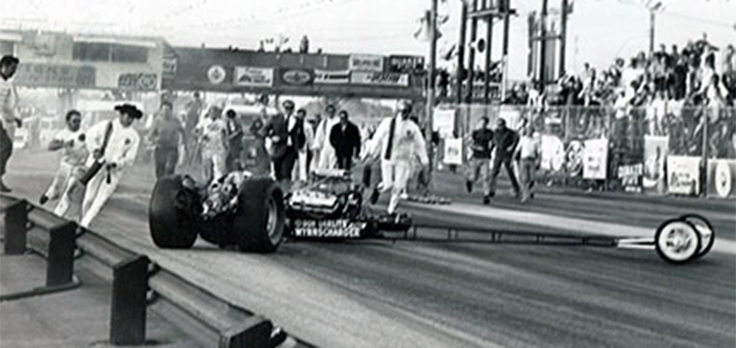

We all know the basics of the story: How Garlits’ experimental transmission in unlucky Swamp Rat 13 exploded on the starting line in the final round of the AHRA Grand Am at Lions Dragstrip in March 1970, slicing his right foot in half, and how, from his hospital bed, he came up with his design for the rear-engine car and debuted it a year later at Lions and then went on to win the NHRA Winternationals.

Prudhomme was there when Garlits blew up, and when he returned, but his involvement in the story is so much deeper than that.

“In those days, it was M&H and Goodyear [tires] and sometimes we would run both,” he explained. “We tested for Goodyear at match races and they would pay us good money to do it, and if you broke anything, they'd pay for that too.

“Anyway, we're testing tires — this was sometime in 1969 — and I heard something funny when Garlits ran. He hauled ass. I walked over to his car and I looked down in the cockpit, and he had a two-speed [transmission] bolted right onto the bellhousing. At the time, we were all running direct drive; no transmission. He saw me look in there and yelled, 'Snake, get out of here!' He went crazy because I was looking there. I found out it was built by this guy Leonard Abbott of Lenco, so I immediately went down to Leonard's place in San Diego, and he built me one, and Garlits was so pissed off at Leonard because we went and won Indy with it, and the two-speed just changed the world.

“He was so pissed off at Leonard that he built his own new transmission, and then the race inside of it slipped or something at Lions, and it blew up. And, again, we might not ever have had a rear-engine dragster if that hadn't happened.”

Prudhomme was in the staging lanes at Lions when Garlits’ transmission exploded.

“I was in the lanes in my Funny Car — you can see my car in the background in some of the photos — the body was up a little bit because we were fixing to run after him, then there was this big flash, I jumped out of the car, and, sure enough, there he was. Car broke in half. I really didn't know what the hell happened. I thought he was all done; his foot was pretty well cut off.

“He was already old. He was in his 30s [he had just turned 38] … like old, right? We thought, 'He'll never come back.' Before that ever happened, [NHRA official] Bernie Partridge had said to me, ‘Garlits is fixing to turn 40 soon; do you think he can still drive at 40? Don't you think that's too old?' I kinda thought so, because back then we didn't know anybody that old. [By comparison, Prudhomme was just 28.]

“Anyway, ‘Mongoose’ [Tom McEwen] and I went to the hospital to visit him, and he’s talking about building a rear-engine car, which we thought sounded kinda crazy. I mean, there were a few guys who tried rear-engine cars. Probably the most successful one was the sidewinder that Jack Chrisman had, but there weren’t too many successful ones. They were kind of a joke in a way.

“One of the big problems is you couldn't really feel it because you were not sitting next to the rear wheels, so when it went to the right or to the left, you couldn't tell it when you're sitting up front, and next thing you know, they tip over or crash.”

What, me worry?

I asked Prudhomme if, in the wake of John Mulligan’s death at the 1969 U.S. Nationals (engine fire) and the loss of Mike Sorokin two years earlier, he thought the venerable slingshot was dangerous and needed a rear-engine car.

“I didn’t, and I don't think Garlits thought so until it happened. I mean, that was the car of choice. The sport was built around front-engine dragsters, and I'd been driving one for going on 10 years before that. That's all we knew.”

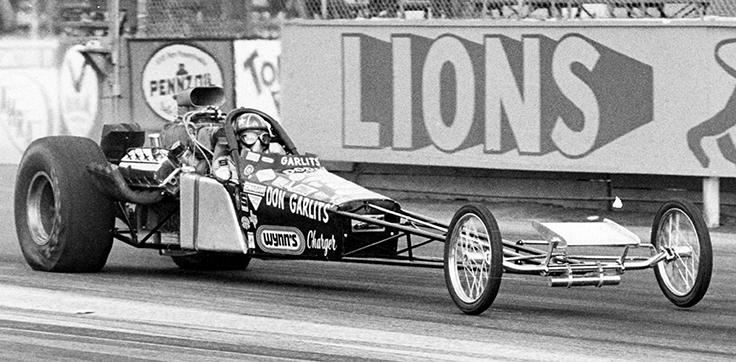

True to his word, Garlits was at Lions a year later with his rear-engine car, but no one wanted to run alongside this “experiment.” Track manager C.J. “Pappy” Hart made him run solo and told him if he crossed any of the barrier lines (center or side), he was done. Garlits went on to runner-up at that event.

“I was on the starting line at Lions when he raced that car for the first time,” recalled Prudhomme. “It was like the moon landing. It changed the sport overnight. As far as I'm concerned, he saved a lot of lives by perfecting the rear-engine dragster. I know people were concerned about running next to him, but I never got that feeling. He was so in control of it. This wasn't some leaker guy running all over the track. It just went right down through there, and I was like, ‘Holy shit.’ Keep in mind, there was no wing on the car — we didn't know about wings — and it went right down through there, and it literally changed drag racing from that day forward. Once he put a wing on it [that summer], that was game over. After that, all you think about is rear-engine cars. They couldn't build them fast enough.”

The Hot Wheels wedge

Despite his undying love for the slingshot design — I remember him telling me a few years ago, “The front-engine dragster, without a doubt, was the most thrilling, most fun thing you could ever possibly have. It was a real turn-me-on-er. The girls fell out of the stands.” — Prudhomme wasted no time putting the danger behind him, but his first experience was less than optimal with the trick-looking but ungodly heavy John Buttera-built Hot Wheels wedge.

“Garlits was really one of the first guys, if not the first guy, who really paid attention to weight on the car, and Buttera, God bless him, he didn't. It was just the way things were. The car looked neat, but you could hardly pick the body up, and it was a disaster. I raced Garlits one time at a little match race, and he just ran away and hid from me, and that was about one of the last times I ran the car. We took it home, took the body off of it, and still ran it. but it was still too heavy. The only thing was you could sure see well out of it, so I had [Kent] Fuller build us a car, the ‘Yellow Feather’ we called it, and it was light, like 1,250 pounds."

Whatever it takes

Prudhomme went on to reminisce about the many lessons that he learned from not only observing but also listening to Garlits and shared a ton of great stories.

“I paid attention to everything he did,” he admitted. “Whenever I could, I’d go up and watch him run. Even though I thought I was pretty good, there was so much to learn.

“I remember we were at some race together — I don’t remember where it was, but it was really hot — and we weren’t supposed to run until night, so we’re back at the hotel; it’s so hot and humid you just want to stay inside. I looked out the window of my room, and there he was working on his car in the parking lot, sweating like a pig. It didn't bother him at all. He was out there with a hacksaw, sawing the bottom framerails to take a piece out of it to jack the engine up because he knew where we were running was going to be slippery, and if he jacked the engine up, he’d have more traction. That's how badly he always wanted to win. He just cut it, took out a piece, and welded it back together, then went out there and kicked everyone's ass.”

[The story sounded so outrageous that I had to call Garlits to fact-check that tale, and it’s true. “Yes, yes, that's exactly right,” he told me. “It was Swamp Rat 25. I cut a quarter of an inch out of the bottom framerail on each side, and that raised it up, and I put a slip tube in there and welded it back. Then I took the two little quarter-inch rings, I put them on a little tie, wrapped and mailed them to 'the Snake' with a little note that said, 'This is a speed secret,' and you look at two pieces, a quarter-inch of inch and a quarter tubing and wonder how the hell could this be a speed secret. Well, I built a damn car. If something was wrong with that, I didn't mind cutting them up. I had a heli-arc welder in my trailer so I could make modifications like that if I wanted to.”]

Prudhomme continued, “That's what made it really, really impressive and really showed me, to be honest, that the harder you work, the luckier you got. Garlits was like that. I mean, he was beyond anybody that I knew. His work ethic and how much he could work, even in the heat.

“One time, we broke down on the freeway out in Illinois. My truck was broke down on the side of the road. Garlits was going to the same race, saw us, and pulled in, which was cool. We hooked my trailer onto his truck and towed it to the dragstrip and parked my trailer, then went back and got his, and what blew me away was I'm driving his truck, that black Dodge truck, that thing had no air conditioning. Being a California guy, I couldn't imagine going any place without air conditioning with the heat and the humidity. His firesuit was in the truck, and it smelled like it came off of a gorilla. I had to hang my head out the door. I finally asked him, 'Why don’t you have air conditioning?’ He says, ‘Snake, it makes me meaner when I get to the racetrack.’

“I'll never forget that.”

More lessons from ‘Big Daddy’

"Garlits, man, he was all about the weight. He knew. As I recall, he was the first guy to run aluminum heads on a Hemi, and we ran them on the Yellow Feather, and it hauled ass, but Garlits really showed everyone that you needed to ground the exhaust chambers out of those heads because they would burn on the exhaust side of the engine. He ground it all out, got the flame pattern away from a part where it would burn.”

[Garlits confirmed: “I only ran the steel heads just a few times, and I got right on that single-plug NASCAR head. You had to be really careful because it had a really thin combustion chamber, and if you ran it too hard, the valves sank down in there. You could tell right away by the clearance. If my valves were getting a little too tight, I knew I was running it too hard."]

“Another thing about Garlits that was amazing is that he didn't blow his shit up. He'd take the spark plugs out after a run, and they looked like they came out of the box. I mean, he was that good with being an engine guy, especially the 426.

“Even when I switched to Funny Cars, he helped me. One time at Union Grove, Wis., I'm in my Funny Car, he's in his rear-engine car, and he's kicking everyone's ass. And I was just hanging by his trailer, and he says, ‘Come here. I want to show you something,’ and he showed me his idle bypass in his engine. Back then, there wasn't much. It was a fuel pump and then the barrel valve, and there weren’t a lot of things you could change, but he knew how to do it.

“Back then, all of the cars, including mine, when they were at the starting line, there's flames coming out of the pipes, but he could turn his idle check valve up with a lot of pressure in it, and run his fuel shutoff like halfway off, so when he did a burnout and back up, there was really no flames, but there was fuel going in, and it cooled the fire off, but when [you] turned the fuel on all the way after staging and hit the throttle, it wanted to rip your head off. I mean, it really worked. And we came back to California and kicked everyone's ass.

[I asked Garlits about all this, and he agreed. “All those young guys, they watched us older guys, and they picked up the tricks, and that's what made them winners,” he told me. “They weren’t afraid to look at some of the guys who had been there before them.”]

The Big Payback

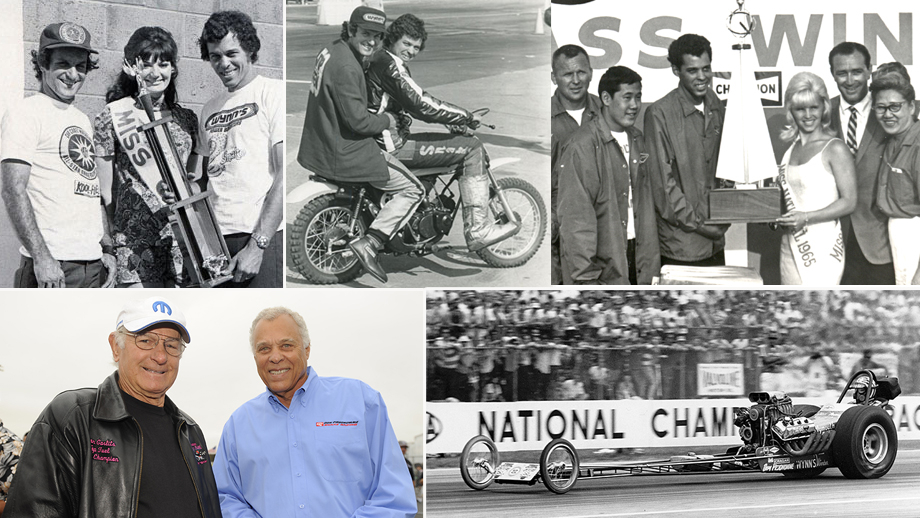

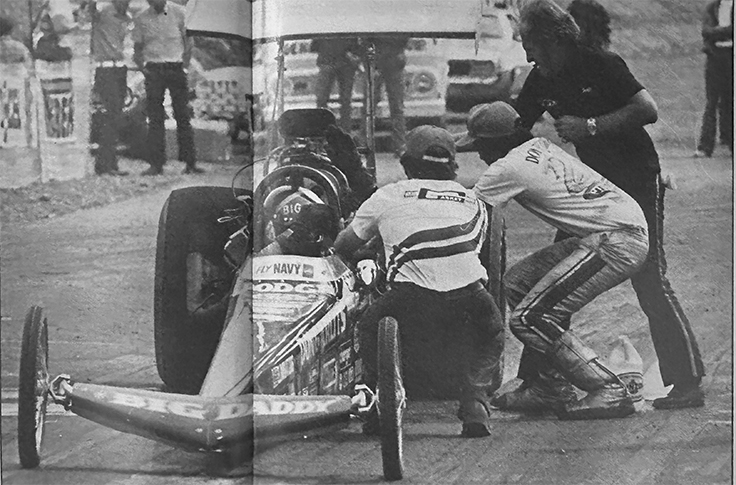

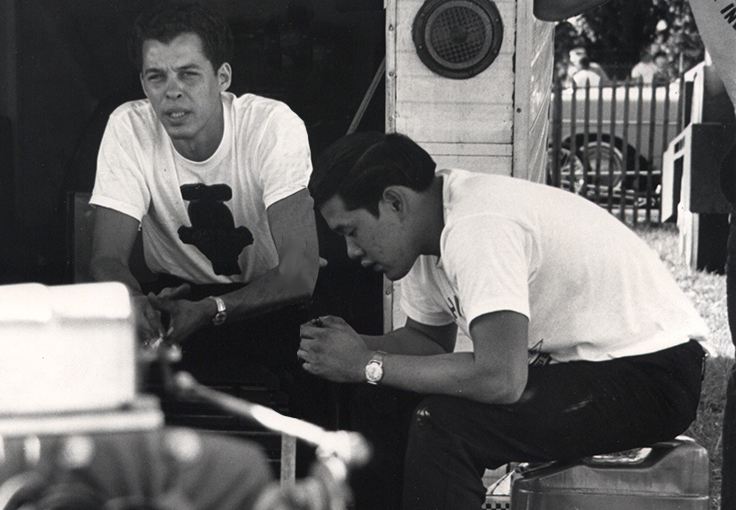

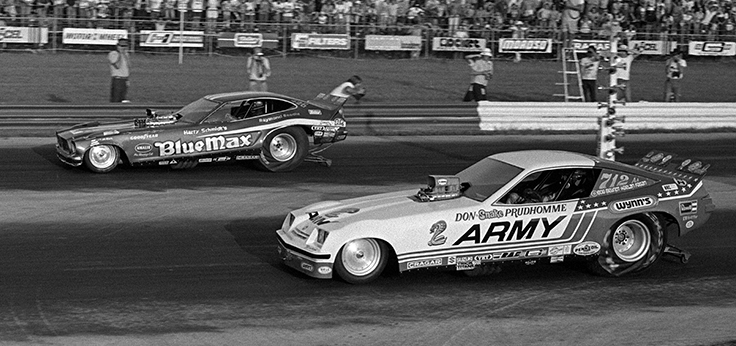

There was a memorable time that Prudhomme saved Garlits’ butt. I remembered as a young fan reading Drag Racing USA’s coverage of the AHRA Springnationals in Spokane, Wash. There’s the great Barry Wiggins photo above showing Prudhomme leaping into action to fix some crossed plug wires on Garlits’ car right before he faced Jerry Ruth in the semifinals.

The story explained, “In their haste to switch engines in the allotted one hour between rounds, one of Garlits’ crew reversed two plug wires. Prudhomme, standing on the starting line, knew by the pop-pop sound when Garlits fired exactly what was wrong. And before Garlits burned through to the line, 'Snake' rushed over and saved his former archrival and foe from almost certain defeat by correcting the ignition wire mix-up!"

Garlits went on to beat Ruth 6.23 to 6.27, and although Garlits lost the final to Gary Beck, it was truly a memorable moment.

I also saw on Facebook recently a similar photo (above) taken at the event by the late, great Jim Kelly, so I asked Prudhomme about it.

“Yes, I remember that,” he said. “I would never miss a run he made; he was that good. Anyhow, I could see his pipes were misfiring, and one pipe was squirting fuel out of it, so I put my hand up to stop him, and I noticed that two of the plug wires were in the wrong hole. There were little rubber boots on the wires, but I didn't know if I would get shocked or not, but said, 'Screw it. I think I'll be all right,’ and I pulled them up and changed them over, and the car started hitting on all eight, and he won the race.”

The Mutual Admiration Society

As we finished talking about Garlits, I expressed my appreciation to Prudhomme that he felt that way about “Big Daddy.” I mean, it’s not like I’ve never heard him talk about Garlits before, but not like this.

“You didn't know I felt that way?” he said, sounding surprised. “I guess I never really talked about it. For such a long time, he was such an ornery bastard; he was so intense until it was hard to be around sometimes.”

(I reminded him that a lot of people — fellow racers, fans, future NHRA National Dragster editors — used to feel that way about him, too, back in the 1970s, when all he wanted to do was win — no time for autographs or chit-chat or socializing. Years ago, when I said the same thing to him, he agreed, “Yeah, I was kind of an a-hole back then, wasn’t I?”)

“But the first time I met Garlits, I could see he was so smart and so dedicated and would outwork anybody. I knew if I ever wanted to be the best, I had to get by him. At one time, I thought he could walk across water, especially in the early days. Garlits is a total hero of mine, and I think when it's all said and done, he's still the ‘Big Daddy,’ the most amazing drag racer I've ever seen in my life.

“I didn’t know what he thought about me all these years, but a funny thing happened after he read my book. He called me and was just so complimentary to me about the book and how our lives were similar, with cars and the automotive stuff [Phil note: Read my past column about their many eerie similarities] and working our ass off. He read what I went through; it wasn't one of those easy lives where you had rich parents or something. And for sure, he didn't either. I got the feeling that he kind of understood me a lot more after reading my book. It was very nice.”

So when I had Garlits on the phone earlier, I shared some of Prudhomme’s thoughts about him and asked for his reaction. Turns out "the Snake” also had recently texted Garlits about the “moon landing” comparison.

“I couldn't believe he was saying that,” Garlits told me. “My God, coming from ‘the Snake,’ I was just blown away. We were fierce competitors back in the day, but it ain't that way anymore. We're super friends. He was very complimentary.”

I told Garlits that I thought that he and Prudhomme were monuments to our sport, two of the greatest to ever do it. “Sure, John Force has way more wins than both of you combined, but it was a different era,” I added.

He stopped me right there.

“Let me tell you about John Force, Phil,” Garlits said. “Nobody can take anything away from John Force. He's one of the greatest drag racers who ever lived. He's done more for the sport than anybody, and the money he's spent on the sport. I'm a No. 1 fan of John Force, and what I really like about him is that he came from nothing, just like we did. Came out of a single-wide trailer. I mean, I know all about John Force. He earned everything.”

‘The Snake’ talks Indy

After Prudhomme was through lionizing Garlits, since I had him on the phone anyway, could we talk about the upcoming U.S. Nationals and what it means to him?

“Man, I was just possessed with that race,” he said. “It meant everything. Still does.

“I remember the first time we went there, me and Ro [Roland Leong] in 1965, and won the [sucker]. That was the first time I was ever there. I didn't realize how big a deal it was until we got there, because people from the East Coast to Florida to wherever would come to Indy. It was in the center of the country; basically, everybody that you ever heard of was at the Indy race. Once I won Indy, I quit painting cars and decided to become a professional driver.”

Prudhomme wouldn’t win the Nationals again until 1969, then famously won it again in 1970 in the unforgettable explosive final round against Jim Nicoll, and won it four times in Funny Car in the 1970s, but he thinks the 1969 race was pivotal.

“In '69, we blew an engine in the semi's. I had looked at the plugs. I had one plug that was oily, but we didn't have time to do anything about it. You couldn't take the heads off and do all the stuff you do in today's world. So it threw the rods out of it in the lights, and in those days, we just weren't set up to change engines that quickly. And then it started to rain. And when I say rain, man, it poured, and we thought maybe we had enough time to change the engine. We worked in the rain, put a motor together, and when it quit raining, went up there and won the final. That impressed Garlits. I can remember him because he was down there, and I think he knew that I was going to be someone to reckon with, that I would be tough.”

What qualifying sessions?

In the 1960s, there was no such thing as the qualifying sessions as we know them today. When the staging lanes got full enough of a certain class, NHRA would run them. If you had the stamina, you could pretty much make as many runs as you wanted.

“You could run once, twice, five times, 10 times, as long as you can get your car back in line and you were ready to run when they said run Top Fuel cars,” remembered Prudhomme. “But the bitch was that you’d come back and get in the staging lines instead of going to your pit to work on the car and sometimes we had to change the goddamn motor. It was very common in those days to see a dead Elephant [Hemi engine] on the side of the road that somebody took out and put another one in. You might not go back to your pits the whole day unless you knew we weren't going to run much anymore.

“We used to get up in the middle of the night and go out there and push the car in the staging lanes — jump the fence if we had to — because we wanted to be the first ones to run.”

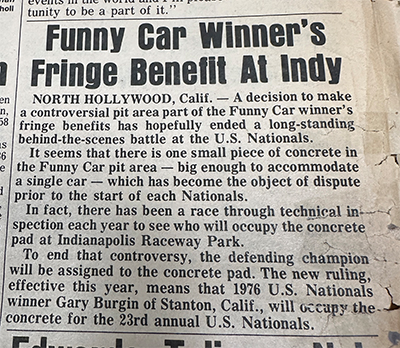

The Slab in Indy

Back in the day, the nitro cars were pitted on the west side of Indianapolis Raceway Park, which is just a sea of grass that would turn muddy when it rained, as it often did in the summertime, as O.G. Smith famously anti-namechecks in his song “Little Green Apples.”

There was but one small island of concrete on that side, near an exit gate out to a bordering side street. The gate was closed during the race, so it made an ideal pit spot. The racers called it “the slab,” and competition for the spot was so fierce that the first race of the U.S. Nationals was usually the one to reach that spot.

“We always tried to be the first one in line, and we went for that spot,” recalled Prudhomme. “It pissed everybody else off in the pit that we got that spot, and I didn't blame them. I mean, there was grass and mud you had to work in. I remember going to Indy in the early days when we'd go to the hardware store and buy sheets of plywood to put underneath our car to stay out of the mud."

NHRA finally got tired of the bickering and, after the 1976 event, decreed that the previous year’s Funny Car winner would get the spot the next year. Gary Burgin famously beat Prudhomme in that 1976 final to spoil “the Snake’s” otherwise-perfect season, then Prudhomme won the 1977 race, then lost the spot to old pal McEwen at the 1978 event.

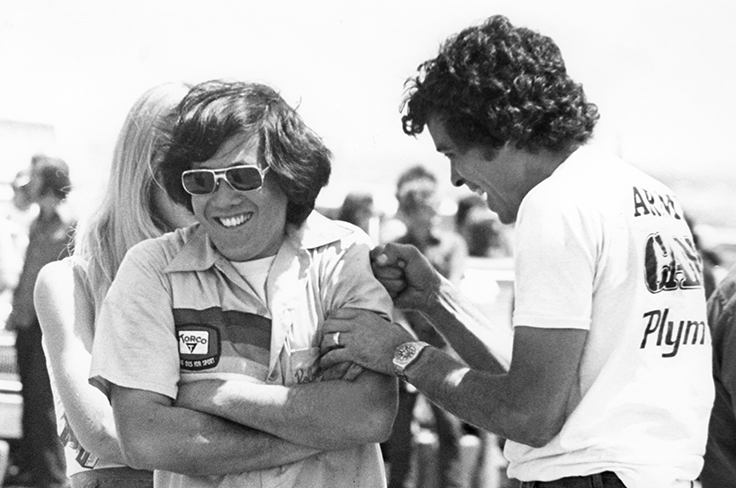

Punching back

Incredibly, Prudhomme reached the Indy Funny Car final six straight years (1973-78), but after winning Indy back-to-back in 1973 and 1974, he lost the 1975 final to Raymond Beadle and the 1976 crown to Burgin despite being in the middle of two of the greatest Funny Car seasons in history.

What happened, “Snake?”

“We had our way with them for a while, but some of the other guys started catching up," he rationalized. "Dale Emery started working on the Blue Max for Raymond, and they had plenty of dough, and they were good. Emery was better than me when it comes to the engine and the fuel system and all that. People started hiring actual 'crew chiefs' to work on the cars, instead of the drivers, like we all grew up doing. Back in the day, I never called Bob Brandt my crew chief. That word wasn't really thrown around back then like it is today. We worked on the car together and shared ideas.

“Beadle, he was cool, you know; we hung out, but I didn't really like Gary Burgin; we didn't get along. There's this guy who used to work for me, but we didn't get along. I fired him or whatever, and he went to work for Burgin and took a bunch of my T-shirts and sewed them together and laid them underneath his car to use as a blanket. That pissed me off. I beat the shit out of him, and then Burgin called me something, so I punched him.”

Wait, “the Snake” served up knuckle sandwiches? And we thought it was just Ed McCulloch …

“I wasn't a real fighter like McCulloch,” Prudhomme admitted. “When ‘Ace’ hit you, you'd be done; I knew I still had more to do after my first punch.

“One time we were running the Funny Car at Martin, Mich. — we hauled ass over there; it was a good night — and coming up the return road where the fans were right there on the chain-link fence, some fan threw something at me — a Coke, I think it was — and it hit me right in the face in the cockpit. I grabbed the brake, jumped over the fence, and ran after that guy and beat the shit out of him right out in the parking lot. The cops didn't do anything about it; they told him it was no big deal. Stuff like that was common back then; you could get away with it back then; sponsors weren't what they are today."

The importance of looking good

“I was always wanting to do more for the sport, and so did Wally [Parks]. We tried to put on a tie and go visit sponsors, and had crew uniforms. I was a big Indy car fan, and the way those guys dressed compared to the way we dressed, we looked like shit. I remember guys used to go out on the starting line before they had reversers to push the car back, and their ass was hanging out. That drove Wally crazy. So when I had the Shelby Super Snake in 1967, that Ford logo was so cool I thought it would look nice on a shirt, and this place called Bowler's Shirt and Uniform [still in business, as it turns out] made us white shirts with a Ford logo on it, and that was pretty cool. We all started wearing uniforms after that.

“When I look back at all that stuff, it’s amazing how it all changed and evolved. We were building the sport up, but no one — I mean, no one — had a clue that drag racing would last this long or become this professional. I’m proud to have been a part of it, man. I really am.”

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator