The Hot Rod Story

The 2021 NHRA season was a yearlong celebration of NHRA’s 70th anniversary, an opportunity for us to reflect on its humble beginnings and stand in awe of how big NHRA has grown from the seeds planted by a letter to Hot Rod magazine editor Wally Parks in early 1951.

As the year rolls towards its conclusion, I chanced upon a somewhat weathered and worn promotional pamphlet produced by the NHRA called The Hot Rod Story, the text of which came from a Hot Rod magazine story of the same name that appeared in the March 1952 issue.

Lee O. Ryan, one of Parks' steadfast editorial allies in the early 1950s, was credited with writing the article, but I’ve read enough of Wally’s distinctive prose and am familiar enough with him not wanting his name on certain works (including the planted letter to the editor) to question who actually authored what reads almost like the Gettysburg Address of NHRA and begins thusly: “In villages, towns and great cities throughout the United States, wherever American youth manifests an inordinate interest in automobiles …:”

By way of introduction and back story, Ryan first came into Parks’ world in the late 1940s before there even was a Hot Rod magazine. According to Parks, as recounted in his son Richard’s fascinating and encyclopedic history of Wally’s life, Ryan was the senior member of a small group of laid-off film studio workers in 1947 who formed Hollywood Publicity Associates (HPA) and began seeking clients for their services. Among their group was a young unemployed studio lot messenger named Robert Petersen. You can kind of see where this is going.

Petersen, known then simply as “Pete” to his friends, loved hot rods and hated the black eye they were getting in the straight press, and reached out to Parks, who then was secretary and general manager of the Southern California Timing Association, for guidance and help to promote the sport of hot rodding. The HPA and SCTA then jointly organized a hot rod show, the “Hot Rod Exposition,” in the old Los Angeles Armory, near Exposition Park in Los Angeles.

Wrote Wally, “Young Bob Petersen was assigned to selling booth space and program advertising, a feat that he carried out aboard a ratty old Harley-Davidson motorcycle; visiting speed shops and equipment manufacturers in and around the Los Angeles area. It was in this venture that Pete recognized the fact there was no publication covering dry lakes or other activities that were fast-growing popular among hot rod enthusiasts all across the country.”

First tentatively titled Auto Craft and funded with a $400 loan (and a free typewriter) from his friend, Bob Lindsay, whose father published a dog-lover’s magazine, Tailwagger, the now-iconic Hot Rod magazine was soon born. At the time, his publishing company was known as Trend but before long became the magazine empire known as Petersen Publications.

But back to The Hot Rod Story. No matter who authored or contributed to it, it’s a masterpiece of a mission statement for the still-nascent NHRA, an incredibly forward-looking and prescient piece that addresses current and future concerns as well as current and future opportunities such as local, regional, and national championships, which were still years away.

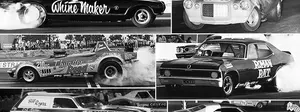

Even though I've added photos from the NHRA archives and the collection of Greg Sharp that were not part of the original story, it still runs nearly 2,300 words; it’s not a quick read, but there’s some priceless prose (“the hot rod movement is … ever-growing, like a tropical garden that requires only wise cultivation to make it fruitful”) and insight to be gleaned if you take the journey. It’s well worth the read for those who lived through this time and struggle, as well as those who have benefitted from it, and once again reinforces the passion and vision of Parks and his allies.

THE HOT ROD STORY

In villages, towns, and great cities throughout the United States, wherever American youth manifests an inordinate interest in automobiles, are to be found hot rods, the mechanical phenomena which enchants so many thousands of young Americans.

Like baseball, basketball, and similar activities that are natively American, hot rodding, as a sport, has spread across all 48 states and even now is being embraced by the youth of other nations.

No one is quite sure when the hot rod sport, as it is known today, had its inception. Information concerning the origin of the term hot rod, used to describe a souped-up car, altered in greater or lesser degree from original factory specifications, is likewise obscure.

But whatever the origin and no matter how great the degree of resentment that originally attached itself to the term, hot rod has become a part of the American lexicon, just as six shooters came to be accepted as descriptive of Mr. Colt's famed firearm of frontier days.

The term never has actually been in bad repute despite the fact that it lends itself admirably to the convenience of sensation-seeking journalists, most of whom would not be able to differentiate between a real hot rod and a Stanley Steamer. For purposes of sensation, the name hot rod is often employed when in reality the newspaper headline writers are referring to an antiquated piece of junk popularly known as a jalopy or clunker. These same journalists would not confuse an MD with a chiropractor but, for some perverse reason, many of them persist in their inability to distinguish between types of automobiles, with the result that the term hot rod frequently appears in front-page stories concerning an accident when quite another type of car is involved.

Thus it is that much of the stigma which has attached itself to hot rodding is totally unwarranted, although hot rod owners in many instances — especially in the past — have warranted (and continue to warrant) the censure and criticism that have been leveled at them.

That there would be law violations, particularly speeding and recklessness among hot rodders, to whom the hobby or sport is new, is not especially startling even though it is not to be condoned or ignored. It is not startling because until most recently these novices have had no organization to look to which could channel their energies into constructive conduits and direct their activities along well-defined organizational lines.

An 18-year-old boy in Midland, U.S.A., for example, spends a year or two or three, devoting all of his spare time to the building of a hot rod. Possibly, there are a few other boys in the city who already own hot rods, and they are waiting to challenge him to a test of speed. Unless the new hot rodder and his companions are taught otherwise, in all likelihood they will hold a drag race on some isolated street or stretch of highway. It's exciting, so they'll probably repeat the performance until an accident occurs or the police put a stop to it.

The foregoing is an example of the typical experience of the new hot rod owner who didn't know exactly what else he could do with his car, especially if he had concentrated on speed and power instead of design and beauty during the period of construction.

There is no longer any need for this evolutionary period of derring-do, and recklessness, to exist. Clubs and association organizations, with stringent rules covering sponsored off-the-street competition, have become (or are becoming) the order of the day wherever there is interest in hot rods.

The "growing pains" period seems to have passed. The thousands of youngsters who interest themselves in the hot rod sport each year now have a pattern to follow: a pattern of organization which provides not only an outlet for their exuberance but far greater fun and satisfaction than ever could be found in disorganized madcap activity such as street racing and allied of recklessness.

Law enforcement officers throughout the country are not unanimous in the opinion that organization and off-the-street competition events constitute the complete solution to what they call "the hot rod problem" but most of them who have made a sincere study of the situation are agreed that it is the solution. Those officers in various sections of the country who have had an opportunity to associate with hot rodders on an intimate basis are especially emphatic in their assertions that organization, supervision, and cooperation comprise the only answer. California, sometimes called the cradle of hot rodding, has supplied a shining example of the efficacy of such an attitude by police officials.

No one knows exactly how many hot rod enthusiasts there are in the United States, considering only the amateurs and not the professionals who build cars for track racing. No one knows exactly how many cars there are that properly could be termed hot rods.

The observation may be made with finality, however, that the number is ever-growing. Interest in hot rods was given impetus by World War II, when untold thousands of youth began to develop a fascination for things mechanical and privileged to increase their knowledge of engines. This degree of interest is again noticeable in the present conflict it expresses itself in peacetime principally through hot rod activities. This, in turn, begets greater interest part of younger boys not of service age.

In 1945, at the close of the war, there probably were more than 3,000 hot rod owners in California. Today, the figure is probably somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000, although more than 25% of these are regular participants in competition events. Most of the non-competition cars have engines and are used principally for transportation. Usually designed with an eye to beauty, these cars are popularly referred to as "street jobs," and it is these cars that generally are featured as exhibits in hot rod shows. The builder of such a car takes just as much pride in ownership as the owner of a super-hot hot rod which has just cracked the 200-mph mark in a Bonneville time trial.

At this point, the two principal facets of the hot rod movement must be considered for purposes of identification and differentiation. Broadly, we may speak of the hot rodders who build cars principally for speed and those who build cars for beauty and originality. It is infrequent that the two are combined, although there exists a neutral zone wherein a beautiful street job can also be an exceedingly fast machine.

As specialization has invaded the hot rod field, it is increasingly evident, however, that the hot rodders concentrate on one type of car or the other, neither group being scornful of the work of the other. Until recently, the non-competition cars have been in the majority, principally because hot rodders, outside of California and one or two other states, have not had the facilities at hand to engage lawfully in competition events such as drag races, time trials, reliability runs, etc. Now, as more facilities are being made available, the emphasis on speed and power in engine development is becoming apparent.

There has been legislation, some of it ill-conceived, curbing hot rod activities in certain states. There has been no evidence to date that it has succeeded in accomplishing much more than to engender a feeling of persecution among hot rodders and to make them feel they have been isolated for special police action.

Certainly, it has not legislated out of existence the love of so many American boys for things mechanical, especially a thing so fascinating as an internal combustion engine.

The preceding paragraphs are set down by way of analyzing the hot rod movement in its principal components, of establishing the scope of the activity, and looking at its faults and virtues.

That it is a field of incalculable potential seems not to be debatable. That hot rodding provides an incomparable proving ground for amateur experimentation and research is not open to question. That out of such activity — be it classified as a sport, hobby, or avocation — may arise some of our foremost engineers and designers of tomorrow is a reasonable speculation.

But whatever the benefits and advantages, whatever the shortcomings and errors, the hot rod movement is a very live, vibrant, vigorous thing — ever-growing like a tropical garden that requires only wise cultivation to make it fruitful. A few far-seeing educators and law enforcement officers already have visualized this potential.

Although the average hot rodder is a highly individualistic being, he nevertheless seeks association with youths who have an identical interest. Such association usually resulted in the formation of a club but there the activity ended.

These clubs became predominantly social units with no clearly defined program of activity and no ultimate goal other than to build good-looking cars. In many communities, organization has not progressed even to the point of club formation, and it is in such communities that criticism of hot rodders is most vehement. In direct ratio to the degree of organization among hot rod owners, the incidence of traffic law violations appears to decrease.

Hot rod clubs that have been organized for some time, and recently have affiliated with the newly created National Hot Rod Association are, for the first time, being provided with a long-range goal — a goal with its attractiveness reposing basically in the prospect of friendly and sportsmanlike competition.

Such competition must, of course, be based on uniformity and standardization, and it is these elements the NHRA hopes to bring to hot rodders throughout the entire nation. There can be no fair competition, whether it be a speed event or simply an exposition where cars are on display for comparison of beauty, design, and originality until the results are based on uniform requisites and regulations.

This job of the organization (one which every genuine hot rodder hopes to see accomplished) is a vast, varied, and costly undertaking but in no measure impossible. It requires guidance and assistance on the community level from qualified sympathizers and from there through the state, zone, area, and national demarcations.

Such organizations must assume the geographical characteristics of the AAU, NCAA, or similar amateur athletic organizations whose activities each year always culminate in a national competition following a sectional elimination process.

It is not sufficient merely to inaugurate club organization and set up a workable program of activity. Continued supervision and direction are required if interest is to be maintained and cohesion is to be given to the entire organizational pattern.

With the centers of hot rod interest so widely scattered, it is obvious that rather an extensive field organization eventually will be required if the NHRA is to achieve the prestige, pre-eminence, and solidness that is its goal. There is not, at present, any adopted formula for recruiting or financing such an organizational staff.

The task of the organization is being made easier by a newly noted spirit of cooperation demonstrated by law enforcement officials in various states; by civic leaders and parents who are accepting the practical down-to-earth approach of the National Hot Rod Association as the only method of bringing about constructive and lasting benefits from hot rod activities.

What Will Organization Achieve?

What the Golden Gloves have done for boxing by way of transforming street fights and alley brawls into supervised boxing contests in the clean atmosphere or a gymnasium, so the NHRA plans to transform the hot rod movement from a disorganized, sporadic, rudderless activity into an integrated regulated and supervised sport.

Such a goal can be accomplished only through an activity that finds its zest in competition. Competition is of necessity limited by the geographical features of the countryside in which hot rod interest exists. But no matter how restricted the facilities on which competition may take place, the NHRA plans to provide a program which will offer an outlet for the natural exuberance of all hot rodders.

Let us start with the simplest form of competition existing among hot rod enthusiasts, the gymkhana. a test of driving skill over an obstacle course. Such an activity provides genuine rivalry, is not basically dangerous, and requires only a limited area for inter-city or inter-state competition which will produce better and more cautious driving habits. A uniform obstacle course pattern can be formulated without difficulty.

Reliability runs, in which the contestants drive over a stipulated course with watcher at checkpoints along the route, is another form of diversion in which rodders may engage no matter in which section of the country they may reside. The specifications of this kind of competition have been worked in infinite detail by the Pasadena Roadster Club of Pasadena, Calif., and their format is considered an excellent model to be followed. Such an activity could easily be extended to a national scale with the assurance of keen competitive interest.

Next, and currently, the type of competition which holds the greatest interest for the greatest number of hot rodders is the drag race, a test of acceleration and speed with two cars running over a measured course from a standing start. This is an exciting pastime but with the hazard element reduced to a minimum when properly conducted under proper conditions. An abandoned airstrip or a facility of similar which permits ample room for acceleration and deceleration and sufficient breadth to give the cars wide clearance is required for drag racing, Fiercely competitive, drag racing is developing some extraordinary speeds.

The same formula of a standing start over a measured course against the clock instead or another car may also be applied with the cars making the fastest times going on to state or sectional competition.

The most limited type of competition, and that to which many hot rod owners aspire, is the time trial runs thus far confined to California and the Bonneville Salt Flats, where vast expanses of smooth runway are available. Time trials have evolved into a highly organized competition employing electronic timers — considered by many experts to be the finest in the world — and run off great punctilio that involves technical inspections, safety checks, and rigid operating rules.

It is not to be expected that time trials can be a source of nationwide competition, due to the lack of adequate facilities in most sections of the country. This does not mean, however, that any hot rodder whose car is capable of competing, could not enter the national finals which now find their embodiment in the Bonneville National Speed Trials held in August each year on the salt flats. This meet has become, in effect, the World Series of hot rod activity and out of it has emerged some extraordinary speed accomplishments.

Apart from the realm of competition, for those hot rod enthusiasts whose primary interest is not speed, there is another type of rivalry manifesting itself. It has taken form in a desire to build or reconstruct a car basically for show purposes. Painstaking attention to detail and beauty goes into this kind of handiwork with vast sums of money being expended to make the car outstanding.

The reward is usually nothing more than a trophy awarded at a hot rod show, plus the admiration and commendation of fellow hot rodders. However, hot rod shows, which had their origin in Los Angeles, are now becoming permanent exposition features in many sections of the country, each one vying with the other for excellence of exhibits. Trophies usually are awarded for the most beautiful car, the most unique car, the best-engineered car, and the best-designed car.

Extended to a sectional, regional, and national basis, this aspect of the hot rod movement offers a most inviting prospect for those whose tastes run to design and beauty rather than speed.

The foregoing are the chief developments in the hot rod field to date but should not be regarded as the end of possible kinds of activity in which hot rodders might engage constructively. Road racing, for example, now a monopoly of sports cars, is an enticing vista.

Summary

In conclusion, it may be stated that a program of organization projected on a nationwide scale is the whole solution to the so-called "hot rod problem.”

The greatest job remains to be done with youngsters 15 years of age, or slightly older, who are just commencing to drive. This group is largely without direction, counsel, or assistance from civic bodies, law enforcement groups, or corporations which normally might be expected to interest themselves in a public relations project dealing with youthful drivers.

It is at this age bracket that boys begin to manifest their fondness for automobiles and speed. In these formative and impressionable years, the doctrine of safe and courteous driving may be brought home forcibly to our youth if the right kind of program is adopted and the proper approach is made.

It is quite within the decision and scope of activity of law enforcement officers or civic groups to embrace and foster an organizational program such as the NHRA offers. This means, in essence, that an attitude of friendly cooperation be substituted for one of suspicion and hostility.

This approach has been found to be successful wherever it has been tried and appears to be the most effective, if not the only, method of approaching the problem.

- End -

Wow, what a fantastic bit of writing. The foresight that went into this piece is amazing, especially because so much of it came true. I often wonder of someone other than Wally Parks could have gotten us here. I'm glad I knew him. Thanks for the long read and, as always, the passion and interest for things past.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator