Saluting U.S. Nationals history: "Ohio George" Montgomery dominates early Nationals

The 65th annual Chevrolet Performance U.S. Nationals is coming up, and promises to be a celebration of the event’s long and rich history. In the months leading up the event, I’ll chronicle some of the great stories that made Indy the world’s biggest and most important drag racing event.

Ask half a dozen different people today to name a U.S. Nationals hero and you’ll probably get half a dozen answers. Bob Glidden. Don Garlits. Don Prudhomme. Ed McCulloch. Tony Schumacher. Frank Manzo.

But if you had asked that question 50 or 60 years ago, there’s little doubt that you’d be hearing the name “George Montgomery” from a lot of folks.

By the time that the Nationals wrapped up its ninth running in 1963, 28 different drivers had already won one of its eight eliminator categories. Twenty-seven of them had won “the Big Go” once to stand proudly upon drag racing’s tallest pedestal.

Only one driver, Montgomery, had won it more than once, and, incredibly, he had won it three times before anyone had even won it twice.

Montgomery’s incredible dominance of NHRA’s most prestigious event is sometimes forgotten to time because he didn’t do it in a blown fuel dragster in one of the sport’s better-publicized classes, yet it’s still an amazing accomplishment in a sterling career that was recently recognized in the announcement of his upcoming induction into the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America.

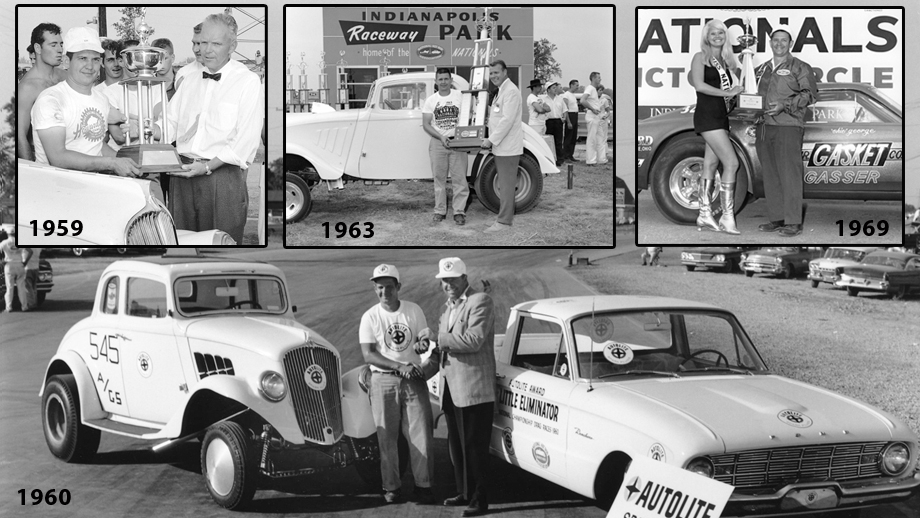

:: DETROIT 1959 ::

Montgomery first won the event in 1959 in its first of two years at Detroit Dragway -- after previous stops in Great Bend, Kan.; Kansas City, and Oklahoma City –- and in the first year that the event began to be called simply “the Nationals.” (From 1955 through 1958, the race had borne the rather stuffy title of NHRA National Championship Drags and it would be known simply as “the Nationals” until 1972, when it adopted the U.S. prefix.)

Montgomery’s weapon of a choice was a baby-blue ’33 Willys powered by a supercharged 390-cid Cadillac engine bored and stroked to 414 inches. Montgomery had been a fan of Cadillac power for years, back to its use in a three-window ’34 Ford Coupe he’d previously built and raced.

“In those days, our first race cars were usually just our street hot rods, and that was a good combination,” told me recently. “Cadillac had a really good engine.”

Montgomery chose the Willys because it was lighter and had a shorter wheelbase –- a full foot shorter –- than the Ford. In late 1958, he found the car in a junkyard, where it was sitting idle and was being used as a plaything by the yard owner’s grandkids. The owner didn’t really want to part with it, but when Montgomery offered him $100 (about $900 in 2019 money), he parted company with it.

Montgomery took it home and installed the Cadillac engine -– then just a 331; the 390 would come the next year -- and added a Detroit Diesel 6-71 blower. And while most of his contemporaries could only get 4-5 pounds of boost out of their blowers, the wily Montgomery was able to engineer his way to getting nine pounds of boost, which made a big difference.

“Having all of the power was a blessing and a curse, because you have to remember that our tires were not made for racing and the tracks were pretty much just polished rock, so we couldn’t use the horsepower we had,” he said. “Low gear was worthless to me; I had to start in second gear. That’s also why the car sat so high in the air to try to get weight transfer.”

Wary of traction woes at Detroit, Montgomery cast a “spare tire” by pouring concrete around a spare Willys wheel and placed it in the trunk to give the car more weight over the back tires. The problem was that the damned thing weighed 600 pounds. He cast a smaller version that only weighed 250, which worked out well (but was subsequently disallowed by NHRA).

Montgomery was entered in A/Gas, the fastest of the classes that made up Little Eliminator, which had made its debut at the ’58 event and gave drivers of slower cars a chance to win an event title rather than having to face the big, bad A/Dragsters for the lone “Top Eliminator” title.

He handily won A/Gas class, then the Little Eliminator shootout over a fledgling speed-shop operator named Jeg Coughlin and his supercharged Chevy-powered D/Gas ’55 Chevy. Coughlin would open the first JEGS speed shop the following year.

“Even back then, winning the Nationals was a big deal,” Montgomery said. “The only event that was even close was also the World Series of Drag Racing in Cordova [Ill.]. Winning the Nationals was everything even back then.”

:: DETROIT 1960 ::

Montgomery won the Nationals again in 1960, running a set of Delco shock absorbers that initially were rejected by NHRA’s Ed Eaton during tech inspection because they weren’t widely available to the public. Montgomery, who at the time worked as a tool maker for Delco, contacted his employer who sent a telegram confirming that the shocks were indeed commercial units made for General Motors.

“I had gotten pretty friendly with the head honchos at Delco and had carte blanche to take any shocks I needed for my racecars,” he remembered. “The corporate people and the engineers all helped me.”

That hurdle cleared, Montgomery again went on to dominate the competition, winning the newly-recategorized A/Gas Supercharged class and then defeating a pair of fellow national record holders in Doug Cook’s C/GS-winning “Screamin’ Meany” Chevy-powered ’41 Willys and Don Breithaupt’s B/A-class winning entry.

Montgomery was in kill mode for the final against Breithaupt and twice jumped the flag start. Unlike today, where leaving too soon is an automatic disqualification, back then the two cars just returned to the starting line to try again. After his second foul, Montgomery was told that a third would result in his disqualification, so he held back but still was able to get the win.

(While most of the faster as cars of the day, including Breithaupt’s, were still push-started, Montgomery’s car had its own starter motor. As crazy as this may sound today, part of the startup procedure involved him blowing into a hose draped over his shoulder to pressurize the fuel tank to get fuel up to the injectors so that he could start the engine.)

Montgomery collected the win and a bounty that included a new Ford Falcon Ranchero that Montgomery still owns today.

:: HISTORY, THEN CONTROVERSY ::

Because the Nationals still was the only event on the calendar, it also made Montgomery’s NHRA’s first de facto multi-event winner. The Winternationals was added in 1961, doubling everyone’s chances to win, and Don Nicholson, Jack Chrisman, and Hugh Tucker all eventually joined Montgomery as two-time winners by the end of the 1963 Winternationals. Montgomery simply surged ahead again by becoming the first three-time winner when he won the Nationals again in 1963.

Montgomery won class at the 1961 Nationals when the event moved to Indy but fell early in the eliminator runoffs, losing his bid for three-peat. He never even got a chance to win the 1962 event as his entry was rejected by NHRA as punishment for public comments that Montgomery had made comparing NHRA unfavorably to another sanctioning body.

Montgomery and NHRA patched up their differences prior to the 1963 event, where Montgomery was eager to show that he hadn’t lost his place in event lore, but another hurdle arose. Between seasons, NHRA had changed the A/GS weight break from five to six pounds per cubic inch, making his big-inch (and heavy) Cadillac engine an albatross. Montgomery reluctantly went in a different direction, switching to a small-block Chevy engine topped by a Roots-style blower and backed to a GM Hydramatic transmission. Montgomery further lightened the Willys by adding a one-piece fiberglass front end and fiberglass doors, allowing him to more freely place the ballast where it was needed as the ongoing battle for traction wore on.

:: INDY 1963 ::

History buffs may also remember that the ’63 Nationals was the first to utilize the new Christmas Tree starting system, and Montgomery proved to be a quick study. He’d seen the new gadget at a regional event preceding the Nationals and quickly understood the value of leaving on the fifth and final amber light instead of waiting for the green as many were instructed to do.

“I can’t say that I was well-versed in how the Tree worked, but maybe a little bit,” he confessed. “They’d tell you, ‘We’ve got these new lights; you’ve got to wait until the green comes on,’ but I figured out you could leave before the green.”

Montgomery again won class and then the Middle Eliminator crown that was one of six eliminators now offered (the others being Top, Little, Jr., Comp, and Stock), defeating the vaunted AA/Street Roadster of California Hugh Tucker, whose mount wouldn’t fire, and, in the final, chased down Gene Altizer’s Chevy-powered A/Gas 51 Anglia to collect his third Nationals win in five years.

:: SUCCESS BREEDS POPULARITY ::

The popularity of the A/Gas Supercharged cars led to nationwide match-race bookings with Montgomery dueling with the likes of Stone, Woods, and Cook. “Big John” Mazmanian, and K.S. Pittman, who were all based in California. It was during this time that Montgomery acquired the “Ohio George” nickname in the advertising wars waged by the cam manufacturers in the weekly drag rags.

“I always ran my car as a legal A/Gas Supercharged at those match races because I felt that was the way to get good at it, but some of the other fellas didn’t, so I didn’t do as well at the match races as I did at the Nationals,” he admitted. “Eventually I started to win more and they stopped coming to the Nationals, saying, ‘Hell, I can’t beat him cheating, how am I going to beat him legal?’ “

His Nationals success also led to an invitation from NHRA President Wally Parks for Montgomery to be part of a team of Americans who traveled to England in 1964 to showcase the sport overseas. Montgomery and Pittman represented the gassers and shared bunk space aboard the racecar-laden ship with the likes of Don Garlits, Tommy Ivo, Tony Nancy, Ronnie Sox, Dave Strickler, Bill Jenkins, Bob Keith and Doug Church.

Montgomery’s success also led to bidding wars among cam makers – Harvey Crane wooed him way from Iskenderian by offering a $2,000 bonus on top of the normal product-only deal – and even auto manufacturers like Ford and Chrysler were eager to not only get on the winning train but to have their engineers work with the skilled and respected Ohioan.

:: FORD'S BETTER IDEA ::

After a “devastating” loss at the ’65 Nationals, Montgomery realized that he’d tapped out the Chevy engine and became associated with Ford, who initially offered him their 289, but Montgomery had his eyes instead on Ford’s new 427-cid SOHC “cammer” engine, which was having some success in the nitro ranks with Connie Kalitta, Pete Robinson, Tom Hoover, and others.

“Not only was that engine dynamite but it also got me in with the Ford engineers,” he said. “That made me tough. I wasn’t dumb, but once I got access to their engineers, there was no stopping me.”

With that combination, the Willys could run deep into the 9.30s at nearly 160 mph, which began to get a little dicey. “I’m lucky to be alive today,” he insists. “That car was evil.”

Ford put the Willys into the wind tunnel for him –- it was the first drag car that Ford had put into its tunnel -- and they quickly discovered it created a lot of rear end lift that made the car get ill-handling, and a front spoiler was added (and also frowned upon by NHRA). Ford also hooked him up with its fully automatic C6 transmission, which shifted automatically at 8,800 rpm, giving him one less thing to do in the busy driver’s seat.

Ford was impressed with what Montgomery had done with their engine, but not thrilled that he was doing it with a Willy body. At a Ford Motorsports banquet at the end of 1966, Ford Racing president Charlie Gray expressed his desire for Montgomery to use a Ford body. With his ‘60s gasser mentality, Montgomery assumed that meant a body like the ’40 Ford or maybe a return to the Ford Prefect body with which he had experimented briefly in 1964, but Gray wanted it to be a current-model car, like the still-new Mustang.

“I told him that I didn’t know if I could get a car like that to meet the rules; he just told me, ‘That’s up to you.’ “

The big problem was that the Mustang was a unibody car and the rules required an automotive frame, so Montgomery – with the blessing of NHRA tech guru Bill “Farmer” Dismuke (whom Montgomery swore to secrecy) -- took frame rails from an old Willys and stretched them 10 inches to fit the Mustang body.

Montgomery was able to keep the car top secret until he rolled it out of the trailer in Bristol, Tenn., for the 1967 Springnationals. Tech officials quickly questioned its legality, but Montgomery simply pointed to the tower and told them to pretty much, “Ask Farmer.”

“At that time in history, that car was so advanced, it was probably the best engineered car in drag racing,” Montgomery says humbly. And, predictably, the car did win the Best Engineered Car award.

:: INDY 1969 ::

The car by then was slotted into NHRA’s Super Eliminator, which boasted a wild menagerie of vehicles from fuel altereds to blown gas dragsters to unblown fuel dragsters, full-bodied cars, and T-roadsters.

Montgomery got the car into the winner’s circle two years later at the Springnationals, which by then was being contested at Dallas International Motor Speedway. A few months later, Montgomery claimed his fourth Indy title in the car.

Super Eliminator was not based on just class winners, just a handicapped shootout not unlike Comp today, but with indexes set off of each class’ national record.

Montgomery defeated a lineup of well-known named including Al Bergler, Jerry Gwynn, Paul Stage, and Ron Ellis en route to the title. Gwynn, father of future NHRA Top Fuel star Darrell Gwynn, red-lighted to him in round two, as did Stage, who was the defending event champ in his supercharged dragster.

Stage was a familiar foe to Montgomery. He had beaten “Ohio George” in the final round of the ’68 Springnationals in Englishtown (Montgomery’s only final-round loss) then won Indy later that year. Now Montgomery was in position to do the same thing, but on the semifinal run against Stage in Indy, Montgomery thought he had been defeated again when the Mustang lost power downtrack.

“The idler pulley broke off, and he went right around me,” Montgomery remembers. “It wasn’t until I got to the top end, when my son, Gregg, came down and saw me all dejected that I found out that he had red-lighted. I had to bust my ass to find the parts to fix it for the final, but we did, and then we beat Ron Ellis and his roadster."

Montgomery would go on to revolutionize the sport again with a successful turbocharged version of the Mustang that won the Gatornationals back to back in 1973-74 with a car that many consider to be the father of today’s Pro Mod machines, and a record-smashing turbocharged AA/Modified Compact Pinto.

After he retired from racing in the early 1980s, Montgomery stayed busy building and servicing custom engines; from 1986 through 2001 he supplied all 100 of the Buick V-6 spec engines for the Indy Light series. You can still find him working at George’s Speed Shop, which he opened in 1950 in Dayton, Ohio. It’s the world’s oldest continuously operating speed shop.

Montgomery also was involved in the creation of a great book detailing his life and racing (several images for this article were from book). "Ohio George" Montgomery: Drag Racing's Gasser King can be found on his website, and on Amazon and other online outlets.

You can also guarantee you'll see him every year at the U.S. Nationals, watching the race that he so dominated decades ago.

By today’s standards and measuring sticks, Manzo (11 wins), Schumacher (10), Glidden (nine), Garlits (eight), and Prudhomme (seven) may rank as the most successful drivers in the long history of the Chevrolet Performance U.S. Nationals, but “Ohio George” Montgomery will always hold his place in event lore as its first dominator.

Phil Burgess can reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE