Tom McEwen, in his own words

In mourning the passing of Tom “the Mongoose” McEwen, I mentioned I couple of weeks ago the last official interview I did with him for National Dragster, which took place several years ago, and that I should share it someday, and many of you asked to see it now, so here it is.

In mourning the passing of Tom “the Mongoose” McEwen, I mentioned I couple of weeks ago the last official interview I did with him for National Dragster, which took place several years ago, and that I should share it someday, and many of you asked to see it now, so here it is.

Granted, this was from a few years ago, and I’ve interviewed him on many occasions since when I had questions about this topic or that, but this was the interview I did specifically for National Dragster, to get “the Mongoose” on the record about many topics I had personally wanted to hear. So, here it is, with minor editing of questions and answers for relevance. Enjoy.

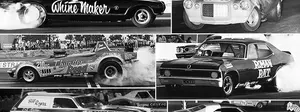

Ask any fan for a short list of drag racing’s all-time-greatest heroes, and you can bet the farm that Tom McEwen, the fabled “Mongoose,” will be on that list. Though he retired from active competition in 1992, the legendary Southern California racer still has a high profile in the sport as a marketing director for a drag racing monthly, color commentator, and friend and mentor to many. Although his win totals don’t come close to matching those of his longtime rival Don “the Snake” Prudhomme, McEwen’s other contributions to the sport, from marketing to safety, long ago assured his place in drag racing’s hall of fame.

Where once he was drag racing’s court jester, willing and eager to promote himself in the media where his contemporary peers wouldn’t, McEwen today is humble. National DRAGSTER Editor Phil Burgess spoke with McEwen about his long career in the sport, his memories and accomplishments.

How does it feel to be a living drag racing legend?

How does it feel to be a living drag racing legend?

In some people’s eyes I am, but not so much in my own. I’ve done some things and have helped the sport, but I never won that many races like Prudhomme. I know I was right there, and without me to beat they wouldn’t be champions, but to be compared to Prudhomme and [Don] Garlits and other such people, I don’t know. I always felt I was a very good driver, but I was never a tuner. There are other people who are bigger heroes than me who don’t get the recognition they deserve, like Ed McCulloch. He has never gotten his true deal. He has won a lot of races, tuned cars, and done a lot of things in the sport, but somehow he gets overlooked a little.

The other difference between me and someone like Prudhomme or Garlits is that I didn’t have that killer instinct every round. Prudhomme was 24-7; me, I liked doing other things. I always knew that was the difference between us, but it never bothered me because I didn’t want to be like those guys.

Does it bother you that Prudhomme always seemed to run better, won championships, and got the bigger sponsors?

I’m not the jealous type; I just made sure I had fun doing what I did. I didn’t let it eat me up.

What kind of rivalry was it?

The rivalry was very serious, and we tried to be friends off the track, but we’re just different people. His fire burned a lot hotter than mine; he was possessed. He hated to lose, especially to me, not that that happened a lot.

You won your fair share.

I have some great memories. Winning in Bakersfield, Calif., [in 1972] when it was a big deal, and the night at Lions [Drag Strip] I drove both my car and the Albertson Olds car to the semi’s. There were three cars, and I had two of them. I told the other guy — I think he was driving the Ernie’s Camera entry — I could beat him with either car, even though the Albertson car was a lot quicker. He picked my car, of course, and I still beat him. That was nice.

And, of course, there’s Indy in 1978, when you beat Prudhomme in the Funny Car final just a few days after your son Jamie died of leukemia.

And, of course, there’s Indy in 1978, when you beat Prudhomme in the Funny Car final just a few days after your son Jamie died of leukemia.

That was a big deal; probably the biggest. Prudhomme always seemed to have a tenth on us back then, so we built a special ring-and-pinion with a shorter gear. We put it in for the semifinals when we had a bye run and it stuck, so we kept it for the final. We made our quickest run, and it all worked out and we won. I turned off into the grass and was sitting in my car crying. The people were going crazy, and Prudhomme came up under the body with me and we shook hands, both of us crying. I think it was probably the only time he didn’t mind getting beat. People still talk to me about it.

Do you miss being in the sport that way, either as a driver or a team owner?

A lot of people ask me that, but I’m not even sure I could put together a deal like that anymore. It’s a salesman’s world. I’m the marketing director for three automotive magazines, dialing for ad dollars, so in a way it’s the same as looking for sponsor money, but we’re talking about $2 to $3 million for the cars. And it’s not just that; it’s also about who has the nicest transporter and who has the biggest building in Indianapolis.

And they all owe it to the Hot Wheels deal, which really showed drag racers what was possible.

And they all owe it to the Hot Wheels deal, which really showed drag racers what was possible.

It really did. Back in those days, you were lucky if you even got product from companies. Before that, I had the Gold Spot/Tirend Activity Booster sponsorship for $1,000 a year, which was good money. The Mattel deal was about $25,000 a year, which doesn’t sound like much now but it was good money back then. You could buy a new Chevrolet back then for $2,000, and I bought my house that year for $39,000.

When we did the Mattel deal, we hooked up with Sports Headliners Management Group, which was representing Mario Andretti and the Unser brothers. The group got us deals with Plymouth, Coca-Cola, Federal-Mogul, Champion Spark Plugs, Wynn’s, and a bunch of other sponsors who wanted to be involved to get their decals on the Hot Wheels cars. That was the first time you saw people getting secondary sponsors because of their primary sponsor.

You’ve driven it all, from gassers to Funny Cars to front-engine and rear-engine dragsters. What was your favorite?

I always liked the Funny Cars more because they’re more of a driver’s car, but I have to admit that when I drove Jack Clark’s Top Fueler in 1991, that was nice. It was a Cadillac, 300 inches long, the motor behind you, going straight as a string.

Warren Johnson said that today’s young Pro Stock drivers wouldn’t have had the same success in the primitive 1970s Pro Stockers. Do you feel the same way about Top Fuel today?

Warren Johnson said that today’s young Pro Stock drivers wouldn’t have had the same success in the primitive 1970s Pro Stockers. Do you feel the same way about Top Fuel today?

The first Top Fuelers I drove were 92 inches long, and you couldn’t see where you were going because the engine was in front of you and the tires were smoking. They wouldn’t go straight — they would sidewind down the track because of all the torque — but you got used to it. You put all of that together, plus parts and oil coming off the engine in front of you and put ’em at Lions at night, and, sure, they’d have problems getting it down the track. I’m sure today’s drivers could learn how to do it, but you wouldn’t get someone jumping into a car and winning in their first few races like we’ve seen recently.

Do you miss driving?

Do you miss driving?

I always liked driving. I started out as a mechanic, maintaining fuel dragsters for guys like Paul Sutherland, but even from when I began racing my mother’s car at Santa Ana in 1953, I liked driving the best. I drove all kinds of cars and just wanted to go faster and faster, but when I look back now at some of the cars I drove it scares me. Some of those cars were welded together with that wire you find under the tar paper in your garage walls. You didn’t think about what you were getting into, and that’s what killed a lot of guys in those early days. Even talented guys like Leonard Harris died that way. He drove a strange car one night because his was broken, and the steering arm came off and he died. We all just wanted to race so bad you didn’t think about it much.

But you’ve had a big involvement in safety over the years.

Sure. We all started out wearing leather jackets, face masks, and gloves because we didn’t know any better; nothing’s worse in a fire than leather. And we learned a lot from the guys who died. Every time someone died, we’d figure out why, then fix it so it never happened again, but we spent a lot of years of finding those weak links.

Other things came about more naturally. When we first began running zoomie headers, the fumes were so bad in the car you couldn’t breathe, so I bought a painter’s mask with the two cartridges and took it over to Bill Simpson, who had just begun sewing things in his garage in Torrance [Calif.], and I had him sew it into a face mask for me. That’s how those started.

Other things came about more naturally. When we first began running zoomie headers, the fumes were so bad in the car you couldn’t breathe, so I bought a painter’s mask with the two cartridges and took it over to Bill Simpson, who had just begun sewing things in his garage in Torrance [Calif.], and I had him sew it into a face mask for me. That’s how those started.

Our Hot Wheels cars advanced safety a lot, too, from advancing firesuits and fire systems in the cars. I always wore two pairs of gloves and a thicker firesuit; it was harder to drive, but I didn’t want to get burned. I also loved working with tire manufacturers, figuring out how to get more rubber to the ground. Tires have come a long way.

You also brought side spill plates to Funny Car racing spoilers.

Oh yeah. The Corvettes had such a short rear deck that it couldn’t trap the air, and at 900 feet the back tires would come off the ground. I made the back spoiler something like 18 inches high, and it still didn’t work. People crashed a lot of Corvettes. Prudhomme and I went to Carburetion Day at the Indy 500 one year, and I told one of their guys about my problem and he suggested spill plates. I came home, put some on, and it helped immediately, and you’ve seen them ever since. I wasn’t doing it to impress anyone, just to save my life.

Any advice for aspiring drivers?

Follow your dream. If you want to do it, just stay after it. Stay in school, so if things don’t work out — because it’s hard to make a living at this — you’ll have something to fall back on during the lean times. Hook up with a team and learn everything you can from the bottom up. Look at Robert Hight.

How would you like to be remembered?

As a good guy. Kind of a smart aleck guy who liked people and enjoyed what he did. I was serious at the track but had fun away from it.

Phil Burgess can reached at pburgess@nhra.com