Top Fuel streamliners, the sequel

|

After Top Fuel’s streamlining experimentation phase in the mid-1960s burned out after just a few years, the conventional slingshot didn’t change much beyond the standard addition of a body to cover the frame of the “rail jobs” — though I wonder if that wasn’t as much to add signage and color to combat the threat to their popularity from the Funny Cars as it was for aerodynamic advantage — until Don Garlits made the rear-engine car work in 1971.

Garlits ran the car first without a rear wing, but then everyone and their brother started adding them to the backs and even the sides of their dragsters. With a new platform on which to experiment, it didn’t take the tinkerers long to begin to cloak their chassis with sleek shapes, most of which were wedge-shaped bodies covering the rear tires and most of the engine. The wedge dragster phase — which lasted roughly three years but spanned only a dozen or so cars — was well-covered in a dozen columns I wrote in April through June 2010 that you can access in the archive at right. Although the cars were neat to look at, again, weight was a factor, and none of them revolutionized the sport, though Don Prudhomme’s car clearly was the best performer of the bunch.

Once that novelty wore off, other than a few experiments (like Don Durbin’s rear-wheel pants in 1977), it wasn’t until 1986 when streamlining got another serious consideration with a pair of sexy-looking dragsters fielded by Garlits and the late Gary Ormsby.

By this time, technology seemed to have caught up with the streamliner craze, and the availability of carbon fiber and Kevlar made dreams of exotic, lightweight bodies a real draw. The fact that NHRA added 100 pounds to the class minimum weight — raising it from 1,700 to 1,800 — was the final clinching point.

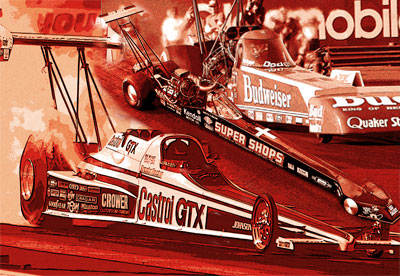

Ormsby and Garlits went at their projects quite differently. Ormsby’s body, backed by many dollars and much hoopla by sponsor Castrol GTX, was conceived and designed by a team of engineers. Garlits’ car was the product of his fertile mind, designed in his head and built by one man.

Ormsby’s car had its origins in the team’s summer home in Indianapolis, where it rented a shop on Gasoline Alley and was surrounded by some of IndyCar racing’s elite. Through a mutual love of fly fishing, crew chief Lee Beard became good friends with those on Roger Penske’s team, whose lead engineer was race car builder Nigel Bennett, who sketched out ideas for Beard.

|

Working from those sketches, noted engineer/aircraft designer Pete Swingler “built” the body on paper, and the body’s dimensions were entered into a computer program that modeled it and did a simulated wind-tunnel test. Eloisa Garza, who designed the Chaparral Indy car for the Jim Hall/Johnny Rutherford team that won the 1981 500, created the body, using a vacuum-formed carbon-fiber/Kevlar composite. The 130-pound body completely covered the engine and pushed air away from the rear tires.

The car had a full belly pan, a front spoiler with splitters to trip air over the front tires — thus eliminating the need for an enclosed front end — and a sunken cockpit with a windshield for Ormsby to look through. The windshield was high enough to direct air over the top of the car, eliminating the need for a full canopy. It looked very much like an Indy car.

While Ormsby’s car was designed to work with the wind, stealthily flowing it around the car’s curves, Garlits’ car was all about punching a hole in the atmosphere and driving through it before it closed.

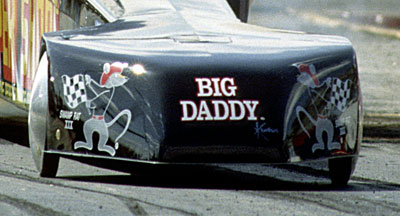

Garlits had a streamliner on his mental jig for more than a year before he built it, and he knew just what he wanted: a tear-drop-shaped nose covering the air-disturbing front tires. Garlits also certainly didn’t need any fancy engineers or computer program. “I have some aerodynamic knowledge from the years and years of dealing with wings and planes and reading books … I am aware of the correct shapes,” he told National DRAGSTER in early 1986.

|

|

Garlits commissioned Mike Magiera, an independent aero consultant who had done work with car companies, to build the nosepiece and worked with ProGlass on the canopy, upon which the “Swamp Rat” had lettered “Rat Under Glass.”

Garlits reported that he liked how the canopy isolated him from the effects of buffeting wind that not only caught the helmet but, in some areas, his hands as well, which would make him a more efficient driver.

“The difference between this car and streamliners in the past is that this car hasn’t deviated from the actual current car design,” he lectured. “It has merely been cleaned up considerably. We haven’t done anything strange that would hurt the performance. We’ve not added any weight; the car is exactly the same weight as last year’s car. It’s not like we put some 200-pound body on it.”

That may have been a direct shot at Ormsby’s car, which was plenty heavy, or even the Jocko Johnson-built Wynn’s Liner, whose body weighed 400 pounds. By contrast, Garlits’ carbon-fiber/Kevlar nosepiece weighed just four pounds.

“Technologically, we’ve come to a point just like the rear-engine car in 1971. We’d reached a plateau of technology where the design was feasible, and that’s exactly what’s happened now. We have reached a plateau in technology where streamliners are feasible, and we have just touched the tip of the iceberg.”

Garlits did announce plans to have a “stage 2” addition to the back of the car to direct air around the tires — nothing as extensive as on Ormsby’s car — but it never came to fruition.

As different as the two cars were in concept and design, so too were their results on the track. Garlits’ Swamp Rat XXX broke the 270-mph barrier in its debut at the Gatornationals and carried him to five victories and the season championship. Ormsby’s car reached just one final round — which it lost to Garlits’ car at the Cajun Nationals in the first all-streamliner final round in Top Fuel history. Garlits went 3-0 against Ormsby in the season.

|

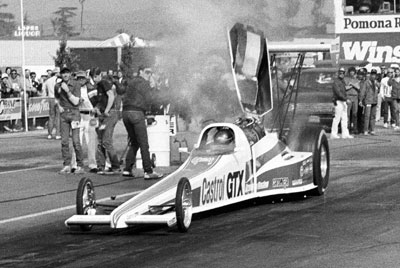

Each got off to a bit of a rocky start. With the eyes of the world upon it at the season-opening Winternationals, Ormsby’s car made it no further than the burnout box on its maiden pass. Though tight body-to-engine clearances might work well in a non-flexing Indy car, when Ormsby stepped on the gas, according to Beard, the chassis torqued, and the body — with just a half-inch clearance — struck and broke the magneto cap, causing an ignition crossfire that banged the supercharger and damaged the body.

“We knew somewhere down the road we were going to do that, but we didn’t think it was going to be on the first burnout,” lamented Ormsby in an interview with National DRAGSTER. With rain wiping out half of qualifying, the car got just one more shot — sans the bodywork — and its 6.47, 152.54-mph pass was nowhere good enough to qualify. A bubble was later added to the bodywork to give 2 inches of clearance to the magneto.

|

Garlits’ new liner wasn’t ready for the Winternationals but debuted at his hometown race in Gainesville, where it didn’t take long for bugs to surface. Because there were no high-speed-rated tires small enough to fit under Garlits’ enclosed front end, he had fashioned some, using high-speed generator fan belts mated to two-piece 14-inch aluminum discs. All was well until the floating front end settled down in the lights when Garlits stepped off the gas, and the belts couldn’t take the sudden run-up to speed and came off the “rims” on every pass, damaging the nosepiece, which had to be repaired after each run. None of that stopped Garlits from qualifying No. 1 at 5.46, 268.01, running a barrier-breaking 272.56-mph speed in the semifinals, and winning the 30th Top Fuel title of his career.

By contrast, Ormsby’s camp was struggling. Beard had resigned for personal reasons after Pomona, and the car was tuned at the next two events by crewmember Dickie Venables in his debut as a crew chief. Ormsby qualified No. 14 and lost in round one in Gainesville and No. 7 and fell in round two, to Garlits, in Atlanta, but, according to Venables, problems persisted because the headers also would torque over and scorch the bodywork. “It was just one thing after another,” remembered Venables in an interview we did last weekend in Charlotte. “That car had a whole bag of problems — it was more problem than it was worth — but we got through it.”

Ormsby then hired the well-respected Bob Brandt — available only because Prudhomme was sitting out the season due to sponsorship woes — to tune the car, which by that time had run a best speed of just 263 mph.

Garlits, meanwhile, already had his eyes set — very prematurely, as it would turn out — on 280 mph.

“As soon as I get the front tires to stay on it, I can really start tuning it,” he said after the Gatornationals. “I was really worried about pitching the belts, and I never really gave that car the tune-up I can. I think, though, that illustrates what this car is capable of. If I had this motor in my ’85 dragster, the one I won the world title with, I would have run between 255 and 258 mph tops. The streamlining and the small front tires are the answer, absolutely, and that's why we got the 270 [272] speed. The car is on the threshold of running 275 or 276, even at the next race, and we could hit 280 by the fall.”

After considering both heat-formed urethane and Kevlar-wrapped tires molded right to a wheel, Garlits settled on 13-inch Goodyear airplane tires that were rated to 350 mph. He ran the car with those for a few events — including the famed March Meet, where he posted a 5.37 (the first pass quicker than Gary Beck’s late-1983 5.39) at 271.90 — but the airplane tire came mounted on its own wheel that couldn’t easily be attached to a standard dragster axle, and there were no provisions for letting air in or out. Goodyear then modified the tire to strengthen the bead and made a change to the compound, and Cragar custom-made the wheels that allowed it all to work.

|

There seemed to be no stopping Garlits. He won the Cajun Nationals and set the national record in Englishtown with a 5.343, 271.08 blast in qualifying. That joy lasted until just the next run when the car flipped overbackward. A lightened fuel load from a prolonged hold on the starting line had the front end light, and when it went up, the air caught under the big nose, and Garlits was a passenger for a frightening tumble. He was unhurt, the car only was surprisingly mildly bent, and he was back at it at the Mile-High Nationals. Although he lost in round one there, he would win the next two events — in Brainerd and Indy (his eighth U.S. Nationals victory) — then was runner-up in Reading, won in Dallas, and secured his third season championship at the NHRA Finals in Pomona, where he also won the Top Fuel Classic bonus event.

By contrast, Ormsby was barely in the top 10 all year and finished sixth, nearly 5,000 points behind Garlits. Brandt had done the best he could with the albatross that he had been handed.

“The car was not only heavy but awkward to work on,” Brandt told me recently. “I could not make changes in the staging lanes with the body attached. It sure was good-looking, and the idea was good, but the trouble with drag cars versus other forms of motorsports is the distance of the race — Indy cars that go many laps versus only a few seconds with drag racing. Not much to aero when we have so little time to race.”

Brandt did tune the car to the Cajun Nationals runner-up, to the No.1 qualifying spot in Columbus, and a pair of semifinal finishes, but the car mostly qualified midpack and generally was in the trailer by the end of the second round. Shelving the body was not a possibility, according to Brandt.

“The sponsorship from Castrol was basically part of the different style of today’s dragsters, and to go back to a conventional car would take away the press they received,” he said. “At least for the first year. There was a lot of money spent to design and build the body.”

Gary Ormsby's team debuted an enclosed front end at the 1987 Southern Nationals, but after the car exhibited some spooky handling characteristics, all of the bodywork was removed shortly afterward.

|

After removing the streamliner bodywork, it didn't take Ormsby long to get his first win of 1987, scoring in Englishtown.

|

Brandt stayed with the team through the winter, during which Jerry Russo made a nosepiece to cover the front wheels, but Brandt was let go after the Winternationals before the new nose could be run, and Beard, who had kept in touch with his good friend Ormsby, rejoined the crew. The team sat out the Gatornationals and Winston Allstars event and resurfaced at the Southern Nationals in Atlanta, but after the car exhibited spooky handling, Beard had the bodywork removed. It didn’t help that Joe Amato’s conventional car — which did include a cockpit canopy — beat them in round one with a national record 279.24 speed, making many begin to wonder about the relevance of streamliners.

“Even though we had put a lot of money and effort into the car, both Gary and I were used to winning, and we made the mutual decision to put a conventional body on the car,” said Beard in another interview I did last weekend in Charlotte. “It’s nice to have a unique car that gets a lot of publicity, but after a while, that wears off, and everyone wants to win.”

After ditching the bodywork, Ormsby scored a runner-up in Columbus, a semifinal in Montreal, and a win in Englishtown.

In an interview later that year in Reading, Ormsby said, “Hindsight is always 20-20. We did what we thought was the right thing to do at the time. Sure, looking at it now, we wish we would have never started with the streamliner this season. It really hurt us.

“It sure feels good to be back in the saddle of a conventional and competitive race car again,” he added. “The whole streamliner deal was very frustrating ... extremely frustrating. It was an exciting project, one we committed a lot of time and money to, but the time came when we had to give up on the deal and, at least for now, move in another direction. It was a real struggle. This sport stops being fun when you’re not competitive. Only so many things can happen to you before you have to get back to basics.”

|

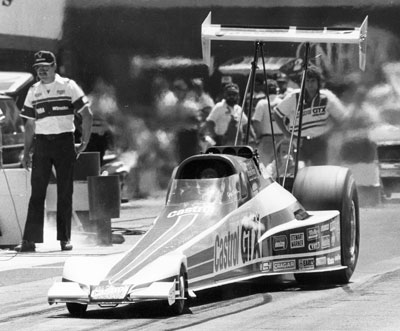

Even though Darrell Gwynn’s conventional car had been the performance star of 1986 — running the five quickest e.t.s (best of 5.26) and four fastest speeds (best of 278.55 mph) — the Gwynn team didn’t win the championship and decided in 1987 to follow Garlits’ lead by debuting a covered-nose, canopied dragster as part of a new Budweiser alliance with Kenny Bernstein. Problems set in early; the engine setback was so severe with the layout that they had to run a shorter B&J transmission instead of a Lenco (remember, kids, this was back when Top Fuelers still ran two-speeds), and the car was ungodly heavy, tipping the scales at 2,100 pounds on an 1,800-pound minimum.

The car qualified just eighth at the Winternationals, and despite reaching the semifinals, the team quickly announced that it was ditching the extra bodywork; the only things kept were the small front tires. At the next race, in Gainesville, Gwynn qualified No. 1 and reset the national record to 5.22 and was runner-up. He ran 5.17 two weeks later at the Allstars at Texas Motorplex and reset the national record to 5.20 in Atlanta, where Amato’s car set the previously mentioned speed record at 279 mph.

|

Amato’s only streamliner experience was similarly short-lived. Just before the Brainerd event in 1986, he unveiled a bullet-nosed streamliner in testing at Maple Grove Raceway, then competed with it in Brainerd. The nosepiece covered a slick fuel tank moved forward with two air tunnels added to create a low-pressure area under the nose to prevent a blowover. The car, predictably, struggled and qualified just No. 12 in Brainerd at only 253 mph (top speed of the meet was 263) and lost in round one. He went back to his conventional car at the next event, the U.S. Nationals, qualified No. 4, and reached the semifinals.

“We didn’t spend enough wind-tunnel time to prove we had the right program,” Amato admitted. “I think streamlining fits if it is put in the right perspective. Aerodynamics are definitely a factor in Top Fuel, but anytime you add aerodynamics, you add weight. If the minimum [weight] for the class was 2,000 pounds [instead of 1,800], then a streamlined body could help you. But if you are giving away 150 to 250 pounds of weight to another car, I don’t think you’re picking that up enough on the aerodynamic side to make up for that. You gain a lot more in performance through clutch and fuel-system technology.”

Independent SoCal Top Fuel racer Butch Blair bought the car from Amato and ran it for several years.

After the mass defections from streamlining in early/mid-1987, clearly, the handwriting was on the wall, and, in a series of interviews with National DRAGSTER that summer, all parties agreed that streamlining was on its way out.

“Streamlining doesn’t seem to be a very good idea in drag racing anymore, does it?” Garlits said. “Personally, we have stopped our streamliner project in its tracks. What you see of our car is what you get for the rest of the year. I mean, why should I go with streamlining? Amato had run 270 mph with the front wheels just hanging out there in the air, and Gwynn has run 5.17 with an open cockpit.”

Still, Garlits soldiered on with Swamp Rat XXX with the only modification being the addition of tabs to the nose that purportedly increased downforce by 30 percent and would prevent blowovers. He had won the season-opening Winternationals but hadn’t been back to a final since.

Garlits had said that in that interview that he would consider going back to a conventional car for 1988, yet debuted in early August.in Brainerd the almost-identical Swamp Rat 31, which had been under construction all that year. A week later, on Aug. 21, Swamp Rat 31 followed on the heels of Swamp Rat XXX and went overbackward, this time in the lights in Spokane, Wash., all but destroying the car. “The Old Man” got pretty banged up, too — breaking two ribs and injuring his back — and didn’t drive a fuel dragster again until 1992.

|

|

Gene Snow, who had been an early adopter in adding a canopy and small front tires (uncovered) at the 1986 Summernationals, also tried his hand briefly with a modern-day wedge, built by Gene Gaddy, at the 1987 Allstars event in Dallas, where it failed to qualify.

The trend toward aero ended in mid-1987 but surprisingly was resurrected, albeit also briefly, six years later when Jim Head, who in the early 1990s was Top Fuel’s “mad scientist,” tested a new car in 1993. Head, long a proponent of removing the rear wing in favor of aero-influenced downforce, built a body with an enclosed rear section (which, unlike Ormsby's car, completely covered the rear tires as well as the engine) and, most importantly to Head, had no conventional rear wing. The car looked great, even unpainted, and seemed to show some potential, but Head had to shelf it after budgetary concerns.

“We made about 10 runs or so and had some stupid things hurt us, and we just ran out of money,” said Head. “But I did run it enough to know it will work. Then in 1994, I got RJR [R.J. Reynolds] as a sponsor [with Camel], and they sure weren't interested in doing that.

“Garlits only addressed the minor problems,” he noted. “The front end is a very minor problem; the cockpit is extremely minor. The wing struts are a little bit of the problem. The big problem is the engine and the headers and the rear wing and the tires. My car only addressed from the roll cage back; Gar's car only from the roll cage forward. Ormsby’s car had too many bite-you-in-the-ass problems, and it still had a wing on it. We have to ditch that rear wing.”

Even though the Ormsby car turned out to be a pretty big flop and time proved Garlits’ forward-thinking to not be a better idea for the time, a lot was learned through the process, according to Beard.

“Not all projects are successful, but you learn from them all,” he said. “The fact it didn’t set the world on fire is disappointing, but we learned a lot about carbon-fiber components, which at the time there were very little, but today, the cars are covered with them. A lot of the concepts from [the Ormsby] car eventually evolved into today’s cars, like shrouding the rear tires, the lips on the bottom of the bodies, the recessed cockpits.”

Perhaps Ormsby best summed up the rage in that late-1987 interview: “We tried and learned that aerodynamic things that should work, according to theory and computer findings, don’t necessarily work on these dragsters,: he said. "The fastest and quickest cars are conventional dragsters. The bottom line is that drag racing is a horsepower sport. What really makes these cars go in that piece of aluminum between the framerails. Unlike IndyCar racing, where there is a smooth transition to high speeds, drag racing is a sport of such violent horsepower that many aerodynamic techniques do not apply. Aerodynamics still play a role, but not as much as pure horsepower.”