Streamliners of the '50s and '60s

|

With all of the talk about aero trickery that has been the natural byproduct of the wheel-pants thread, I’ve received quite a few requests for a more full accounting of Top Fuel streamlining efforts in the sport’s history. It’s a pretty broad topic because all sorts of accoutrements have been added to dragsters throughout the years to cheat the air – front and rear wings to side-mounted canards, belly pans, ground effects, and more – but to keep a more narrow focus, let’s just talk about the best understood and most visual component: bodywork.

As we’ve seen from Craig Breedlove’s 1964 Spirit II streamlined slingshot, drag racers have been working diligently on the concept for decades – sadly, most of the time ultimately unsuccessfully or unsustainably. The bugaboo has always been weight with a dash of inconvenience added for good measure.

When the streamlining craze hit Top Fuel in 1986, National DRAGSTER did a pretty thorough recap of streamlining history, so I drew from that. I’ll cover this in two parts, beginning with the early stuff today (1950s and 1960s) and ending with the more modern stuff (for which a lot more documentation is handy) next time.

Streamlining came in many flavors but for the most part focused on a sleek body and enclosing the rear tires and some attempt at sealing off the driver compartment, either by low position, a windscreen, or a full canopy. Interestingly, few paid much attention to the front tires, which, as we know today, churn up some aero-disturbing turbulence.

|

Perhaps the best known example of mid-1950s aero was Ed and Roy Cortopassi’s Glass Slipper, which is credited with being the first dragster to combine a streamlined body and an enclosed cockpit. It was named America's Most Beautiful Competition Car at the prestigious Oakland Roadster Show in 1957 and, along with 1955 Nationals champ Calvin Rice’s dragster, was hand-chosen by NHRA founder Wally Parks to compete for FIA International Acceleration Records at March Air Force Base in Riverside, Calif., in 1958. It clocked 168.85 mph in the standing kilometer with an unblown 302-cid small-block Chevy. You can read more about those efforts here.

|

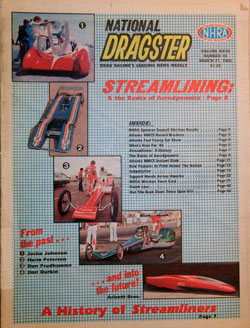

The ever-innovative Mickey Thompson was one of the first to show what might be accomplished with slick bodywork with the Panorama City Special dragster in which he competed at the 1955 Nationals in Great Bend, Kan. Fritz Burns, a real-estate magnate in Southern California’s San Fernando Valley who also owned San Fernando Drag Strip and much of Panorama City, sponsored the car on its trip. This car is also memorable in that it’s believed to be the first successful slingshot-style chassis, with the driver sitting out behind the rear end. The car was short – just more than 97 inches in wheelbase – but featured a sleek body that enclosed the rear tires and a cockpit canopy. The car ran 142 mph; top speed was 151 mph by Lloyd Scott’s dual-engine Bustlebomb dragster.

|

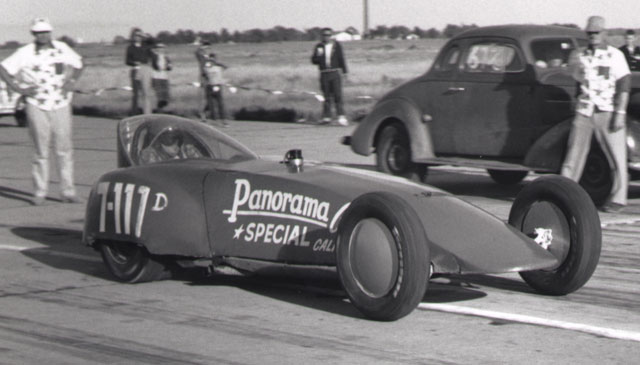

Amarillo, Texas' Jack Moss, whose Rambling Ram nearly won that 1955 Nationals – he was defeated by eventual champ Rice in the dragster class final – built this slick car in 1957 that was powered by twin Chevy engines mounted side by side covered but for some Pro Stock-like hood scoops. The body for the 2 Much was designed by Don’s Custom Shop in Tulsa, Okla., but as good as the car looked, it never ran well, and Moss abandoned the body after a few months.

|

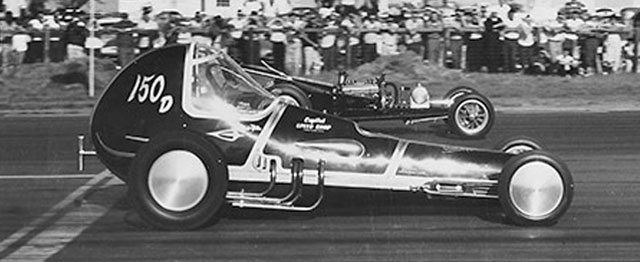

Around the same time (1956-57), this slick-looking back-motor car with a huge aft section showed up at Colton Drag Strip in Southern California, according to NHRA historian Greg Sharp, but none of his research uncovered the owner or driver. “I’ve heard Bean Bandits and other guesses, but maybe if you run it, someone will come up with a positive ID,” he wrote hopefully. Anyone?

|

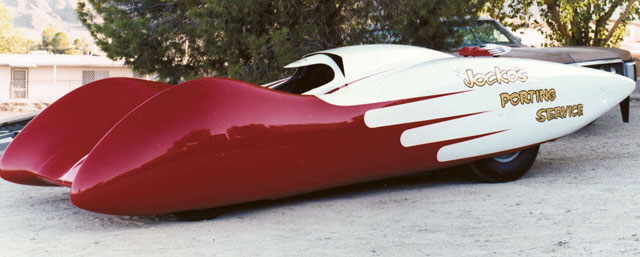

In 1958, forward-thinking Robert “Jocko” Johnson unveiled this stunning creation, which featured the first “full envelope” fiberglass body. Driver Jim ”Jazzy” Nelson built the blown 450-cid engine that powered him and the car to a surprising 8.35, 178.21-mph pass at Southern California’s Riverside Raceway on May 31, 1959, a pass that was the fifth-quickest official time of that year. Johnson built a second car in 1964, using aluminum for the bodywork for its weight-saving value and an Allison V-12 airplane engine for power, but that car was a pretty big flop. This body shape resurfaced, of course, in 1973 on Don Garlits’ unsuccessful Wynn’s Liner.

|

Racers were doing a lot of this work without the aid, of course, of wind tunnels, and though some no doubt were well-researched, others were all about “eyeball aero,” which caused unfavorable things to happen. I’m not sure if aero had anything to do with the crash that claimed the life of Hank Vincent while at the wheel of his swoopy, national-record-setting Top Banana B/FD May 29, 1960, at Fremont Dragstrip in Northern California, but the car reportedly left the track at 170 mph and “leaped in to the air” when he tried to guide it back onto the racing surface, then rolled 300 feet. He died en route to the hospital. According to Sharp, noted Chevy power-meister George Santos (father of former Top Alcohol Dragster world champ Rick) was Vincent’s brother-in-law and crew chief. The car, which also was named America’s Most Beautiful Competition Car at the Oakland Roadster Show in 1959, was advertised (by Hubbard Racing Cams) as the “World’s Fastest Chevy,” running around 170 mph.

|

|

Breedlove’s Spirit II was not the only slick-looking slingshot nor the only streamliner of the mid-1960s. In 1964, the Logghe-Marsh-Steffey team – famed chassis builders Ron and Gene Logghe, driver Jim Marsh, and crew chief Roy Steffey -- built this car, which had everything but the front wheel pants. The team, which had recorded the first unblown seven-second pass with its 389-cid-powered C/FD entry in March, built an identical engine for the streamliner and saw the performance plummet to an 8.25 when the car ran in Indy that year. After a few more races, the car was parked, but not without leaving a bit of mystery. I reached out to Steffey via email to ask about the car’s quick retirement. “We ran both the C/FD and the streamliner at Indy, and it was a tenth slower than the C/FD, and we felt it was due to the extra weight of a full body," he responded. “We later built a blown 354 Chrysler on fuel for the streamliner and took the car to Richmond, Va., around Thanksgiving time as that was the closest track to Michigan that was still open. Maynard Rupp made one half pass to check it out and a second full pass. From the starting line, I could see six feet of daylight under the slicks in the lights, and it was turning sideways. Maynard pulled the chute, and it straightened out. The Prussian [conventional slingshot Top Fueler driven by Rupp and tuned by Steffey] would run over 203 with that engine, but due to Maynard pulling the chute at the first light, who knows what speed the streamliner would have gone if it didn't fly.”

|

In August 1964, the Scrima-Basilek-Milodon-Tuller Scrima-Liner made its debut at Lions. The team, consisting of chassis builders Ron Scrima and George Bacilek, engine man Don Alderson (of Milodon), and driver Goob Tuller, got everyone’s attention with the immaculate machine, but the car never ran as good as it looked, posting just an 8.14 at 191 mph. The car later ran a best of 7.74 without the body.

|

Tommy Ivo’s similar-looking Video-Liner came from the fertile mind of Steve Swaja, whom Ivo met during the famous NHRA trip to England in 1964. Swaja, who was on the trip helping Tony Nancy, was a student at the famous Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, Calif., and drew up sketches of streamliners for both Ivo and Garlits, though only Ivo’s was built. The car had a short life because Ivo found the handling precarious at speed; the rear tires tended to come off the ground in the lights. In his book, “T.V.” Tommy Ivo: Drag Racing’s Master Showman, Ivo says he finally gave up trying to sort out the car after hearing that the driver of another car was killed at Lions while he was waiting to make a run. “That thing wanted to swap ends in the lights because it was a reverse teardrop, and I thought of taking it down some of those lousy tracks, and that’s all it took,” he told Sharp last week. “I went home and built another chassis with the running gear from the Video-Liner and left on tour.”

|

Here’s yet another short-lived streamlined attempt, the Mooneyham-Ferguson-Jackson-Faust machine, whose Jocko-designed metalflake-blue bodywork enclosed not only the cockpit but also the front tires. The sleek-looking piece spent just two days on the track, at Lions Drag Strip and San Fernando Raceway, May 8-9, 1965, and the popular “Jungle Four” SoCal team never ran better than 8.20 at 197.80. Just prior to building this car, the team -- Gene Mooneyham, driver “Jungle Larry" Faust, Wayne Ferguson, and Jerry Jackson -- had set a new Standard 1320 A/FD record of 7.53 at Lions, so the 8.20 was quite a disappointment, but was the body too good? According to Mooneyham’s wife, Dorothy, “The front grabbed the ground like a vacuum cleaner,” perhaps creating too much power-sapping downforce. The car is now in the Garlits museum.

|

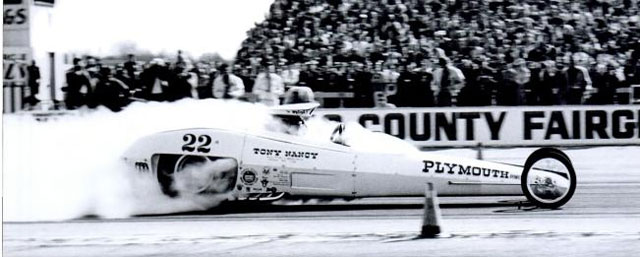

Frank Huszar and Roy Steen built the chassis and Wayne Ewing the body for a pair of sleek rear-engine gas dragsters for Nancy, dubbed Wedge I and Wedge II. The first, which debuted in 1964, used a Wedge-head engine (making the entry name a double entendre) and was destroyed in a crash in Ohio on July 12. A second car, powered by a blown Hemi, was built later that year and was more successful but was parked in mid-1965. Nancy later restored this car before his death in 2004.

|

Pulsator testing sans body at Irwindale (Jere Alhadeff photo)

|

Another slick rear-engine streamliner was built in 1965 by Nye Frank. Dubbed the Pulsator, it was a twin-engine Top Fuel dragster with a design copied from Frank’s other wunderkind, the ultra-successful Freight Train Top Gasser. According to a fine article by George Klass on the Two To Go website, the Pulsator, which like the Train was driven by Bob Muravez (aka Floyd Lippencott Jr.), used two reliable Chevy engines of about 900 horsepower each (comparable single-engine Hemi-powered fuelers had about 1,500 ponies but were damage-prone) under the Nye-built fiberglass body.

“The full body garnered a lot of attention; however, it was cumbersome to work on the car between rounds,” explained Klass. “The body was a two-piece design, with a bottom half and a top half. To work on the engines, check the plugs, run the valves, etc., the entire top half of the body had to be removed from the car. More often than not, for convenience sake, the original Pulsator ran without the body. Of course, the structure, tabs, and framework that held the body panels in place remained welded to the chassis. One night at Lions, Bob popped the chute after a run, and the shroud lines somehow became entangled in this structure, lifting the back of the car completely off the ground and high enough that when the car eventually returned to earth, the landing flattened both pans to the cranks. Not a good thing.”

|

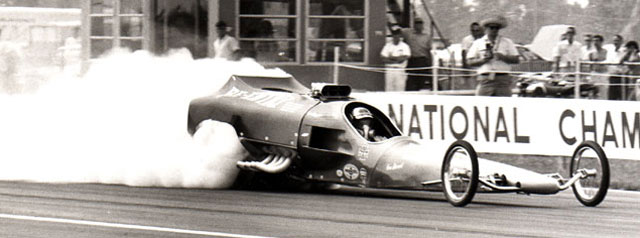

Robert Lindwall’s Re-Entry, which was featured in this column several years ago, certainly looked fast even standing still, but its life was among the shortest of the bunch. Lindwall qualified the car at the 1966 U.S. Nationals, won his first-round race on Bob Stewart’s red-light, then crashed in round two against Connie Kalitta. The car ran 201.34 mph on that pass, which had a tumbling 9.52 e.t., showing some promise perhaps, but the car was not rebuilt.

|

|

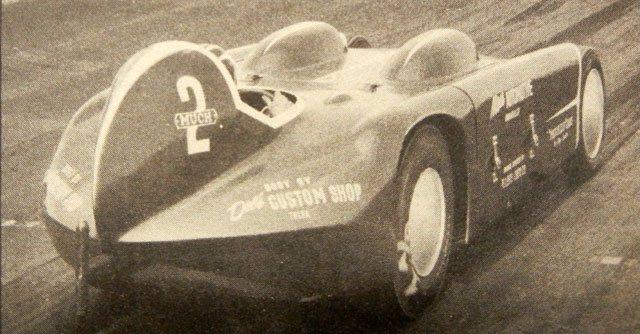

I devoted a two-page spread to this car, the Super Mustang, in a 2010 issue of National DRAGSTER, so I know quite a bit about it. Former DRAGSTER Editor Mike Doherty tabbed the Super Mustang No. 4 in a story called “The Ten Big Mistakes in Drag Racing,” in the October 1970 issue of Drag Racing USA, so that should give you a hint of how things went.

The car was commissioned by Ford as a promotional tool in the winter of 1966 and debuted at the 1967 Winternationals, where Tom McEwen shoed it to a disappointing 8.60 best at 180 mph, and it ran only a few times after. The 150-inch chassis was built by the Logghe brothers and featured a sophisticated rear suspension made up of a posi-traction rear end suspended by a pair of coil-over shocks, traction bars, and an anti-sway bar. The swoopy body was conceived at the Ford Design Center and its shape perfected in Ford’s wind tunnel. A bubble canopy covered the cockpit.

Tom Marsh and Kalitta built the injected 427 SOHC engine, and Kalitta actually did shakedown runs with the car, sans body, in Florida the previous December. McEwen, who got the driving gig because of his previous association with the Brand Ford Top Fuel team and had become friends with Ford highflyers Dick Brannan and Chuck Foulger, barely fit in the cramped cockpit, which didn’t help. “My head was mashed by the canopy,” he told me. “It wasn’t real comfortable. Despite all of the money and brains behind the project, it was, to put it bluntly, a dog.”

The age of aero experimentation seemed to die with the Super Mustang -- it wasn’t until the wedge Top Fuelers of the early 1970s started popping up that aero got another look. I think we’ve covered the whole wedge thing to death with a dozen columns in the summer of 2010 (late arrivers can find them in the archive at the right of the head of this column), so I’ll pick up next time with the brief aero rebirth of the mid-1980s.

I’ll be in Charlotte for the NHRA Four-Wide Nationals beginning Thursday (where I hope to spend time with Lee Beard talking about Gary Ormsby's streamliner) and will file that story next week unless something goes awry. Because it’s an all-day flight home from North Carolina Monday, I'm not sure when that will be, but I hope next Tuesday.