'The Rocketman'

|

Even for a fan who grew up watching them in the 1970s and early 1980s, there was a lot that I didn’t know about rocket cars, but after spending time on the phone last year with "Capt. Jack" McClure and yesterday with “the Rocketman” himself, propulsion wunderkind Ky Michaelson, I know a whole lot more, especially about Michaelson’s most famous car, the Pollution Packer.

As solid as my knowledge is about the wheel-driven side of the sport, I didn’t realize until last week’s column that the Packer made the first four-second and 300-mph runs in NHRA national event history. And, as goofy as this sounds, I never knew the origin of the car’s name, either.

But we’ll get to all of that. First, a little background on Michaelson, whose road to putting an indelible stamp on the sport and the business of entertaining fans has more twists and turns than a climb to Pikes Peak.

Michaelson’s road to dragstrip fame began in the early 1960s while working at the Sno Pony Snowmobile company owned by his across-the-street neighbor, Tony Fox, an enterprising and cunning carny barker of a businessman who not only owned the snowmobile company but also had delved into everything from weight-loss equipment to trash compactors. Michaelson convinced Fox that they could earn a public-relations bonanza for the company by setting a world speed record, so together they built the Sonic Challenger.

Tony Fox, Ky Michaelson, and the record-setting Sonic Challenger

|

The Sonic Challenger had a historic lineage. It was built from the chassis of the famed X-1 rocket car, the first-known hydrogen-peroxide-powered rocket car to take to the dragstrip and a car that shocked everyone in 1967 when driver Chuck Suba powered it to an e.t. of 5.41 at U.S. 30. Michaelson had convinced Fox to buy the car from Reaction Dynamics – a company owned by Pete Farnsworth, Ray Dausman, and Dick Keller, who later would build Gary Gabelich’s land-speed-record-setting Blue Flame -- then took off the X-1’s wheels and put snowmobile tracks on the back and skis on the front (later replaced by skis at all four corners) and drove it into the Guinness World Records book Feb. 15, 1970, in Vermont with a run of 114.5 mph over a quarter-mile course.

Michaelson lost interest in snowmobiling and began a long history in wheel-driven drag racing, especially in Top Gas, and it was NHRA’s decision in 1971 to discontinue the class that led Michaelson to create his first rocket dragster. He had a new rear-engine chassis but no class in which to run it, so he bought the hydrogen-peroxide engine out of the Sonic Challenger from Reaction Dynamics, which sold the car in part to fund the Blue Flame project.

Throughout the years, Michaelson had done a lot of prototype work for Fox’s many companies, but their relationship often was stormy. In fact, at the time that Michaelson decided to build his first rocket car, he wasn’t working for Fox, but the canny Fox talked him back into the fold with the agreement that he would sponsor Michaelson’s new machine through his company that manufactured trash compactors under the Pollution Packer brand name. Thus, the Pollution Packer rocket dragster was born.

(Full disclosure: In the early 1970s, “pollution” was as big a news topic as “recession” is today; I admit that for years – oh, say from 1973 when I first heard of the Pollution Packer until roughly, oh, last week – I figured that Michaelson had just been playing on the buzzword with a car that emitted no hydrocarbons. Silly me.)

When the Pollution Packer debuted in the summer of 1972, it had this striped paint scheme and quickly aimed at taking the title of quickest and fastest rocket car from Bill Frederickson's Courage of Australia (below).

|

|

Michaelson initially drove the car (even before it was rebranded as the Pollution Packer) in May 1972, but the father of seven began to have misgivings about his craft after witnessing an accident involving a Top Fuel dragster and turned the wheel over to his childhood friend Dave Anderson, a journeyman Top Fuel pilot still looking for his big break. He got it with the Pollution Packer.

Fox provided the capital not only for a tractor-trailer rig, but also paint jobs, matching uniforms, and even a helicopter, all of which upped the ante and brought in mountains of PR.

“Tony Fox was all about show business; it was quite a dog-and-pony show,” remembered Michaelson of his late partner, who died recently. “We got a tremendous amount of exposure with that car.”

It didn’t take them long to set their sights on breaking records and making a name for themselves. At the time, the unofficial quickest and fastest rocket dragster belonged to Bill Frederickson, the Courage of Australia – a three-wheeled machine not unlike the Blue Flame – that driver Vic Wilson had wheeled to a stunning 5.107, 311.41 Nov. 11, 1971, at Orange County Int'l Raceway. At the time, the best Top Fuel cars were running in the 6.30s at 230 mph, so the pass – although not sanctioned by any racing body – nonetheless drew oohs and aahs. When the two cars were booked together at Great Lakes Dragaway in Union Grove, Wis., Fox quickly challenged Frederickson to a high-dollar race, putting up $100,000 for bragging rights. “[Frederickson] never took the trailer off the car, and we ended up getting his appearance money,” recalled Michaelson with a hoot.

The Pollution Packer team set 13 records on the Bonneville Salt Flats in late '72.

|

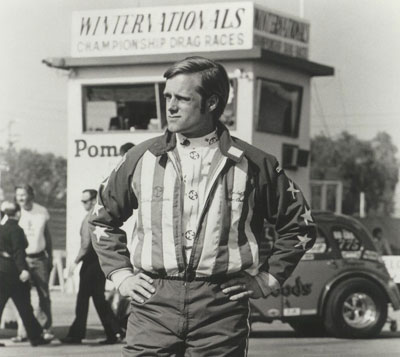

Dave Anderson was the fearless pilot of the Pollution Packer. In its debut at the 1973 Winternationals, the Packer rocketed to a best speed of 297 mph.

|

|

|

The Pollution Packer was already a match race sensation in late 1972 – though not yet legal at NHRA tracks – when Michaelson, Fox, and Anderson went to Bonneville in October 1972 to try to set a record on the Salt. With Anderson sharing cockpit time with female speedster Paula Murphy, they set 13 state, national, and international records.

NHRA was reluctant to license rocket and jet cars, according to Michaelson, in part due to its inexperience with them and a fear of what might happen if the engines in either should fail. But NHRA was certainly enamored of wealthy Fox and his commitment to the sport – which included plans for building a new dragstrip in Minnesota -- and Michaelson believes that that may have gotten NHRA over the hump. Regardless, rocket cars were accepted, and it was Michaelson, Fox, and Anderson who ushered in NHRA’s rocket era with a spectacular debut at the 1973 Winternationals, where Anderson set the crowd abuzz with a run of 5.35 at 297 mph.

A month later, March 15, 1973, they ran the sport’s first official 300-mph pass, 305.08 on a 5.176-second run, and a few months later made the first four-second run, a 4.99, on June 10 at the NHRA Springnationals at National Trail Raceway in Columbus. At the time. only a few Top Fuel cars had ever run in the fives or at more than 240 mph.

Remembered Michaelson, “Don Garlits came over to me and said, ‘Thanks a lot for effing up drag racing.’ We stole the thunder everywhere we went with that car.”

Later that year, Anderson ran 4.62 at 344 mph at the U.S. Nationals, speeds that began to concern Michaelson.

“Tony was always wanting us to go faster,” remembered Michaelson, “and eventually we had a falling-out and went our separate ways.”

Anderson, who enjoyed the fame associated with the car, stayed with Fox and was killed in the car the next March in Charlotte. According to the best understanding that anyone has, the car locked up – either because of driver or mechanical error – and spun backward, rendering useless the parachute. The Packer collided with a car stopped on the return road, killing Anderson and two crewmembers of the other car.

“I cried my heart out,” said Michaelson.

Michaelson fielded rocket cars after that, including the Miss STP dragster in which Murphy suffered a broken back at Sears Point Raceway when her first parachute ripped away the back of the frame to which the chute lines were attached, and the Conklin Comet with Ed Ballinger and Kitty O’Neil.

“No one was ever hurt by an engine explosion in a rocket car,” noted Michaelson. “Everything that was bad happened at the other end in trying to stop them.”

By his count, Michaelson has been involved, either as car builder, owner, or propulsion provider, for 20 rocket cars and set 72 state, national, and international speed records. When the price of rocket fuel skyrocketed and its availability became limited, Michaelson got out of the game in 1980.

Michaelson and his Rocketman Quick Flight Belt: a jet pack for the masses?

|

In the years since, Michaelson has attached rockets to everything from motorcycles to outhouses (really) and even to his teenage son Curt (aka "Capt. Rollerball"), who zipped along at nearly 60 mph on roller skates with a rocket engine strapped to his back. He has built a real-life rocket belt (picture Buck Rogers) and on May 17, 2004, became the first civilian to put a rocket into space when his Civilian Space eXploration Team reached an altitude of 72 miles (“space” begins at 66 miles) and set the record for the fastest anything built by a civilian when the CSXT vehicle – a conventional liquid-fueled rocket -- hit 3,420 mph.

“Can you imagine building something in your garage that you get four sonic booms out of?" he chuckled. "What a thrill. People say, ‘You must be a rocket scientist.’ No, I’m just a hot rodder."

And now you know why they call him “Rocketman.”