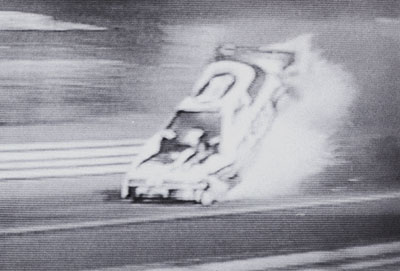

Force's fire-fighting flopper

John Force had quite a trial by fire in the early 1990s, including the famous incident in Memphis, Tenn. (below), after which he proclaimed, "I saw Elvis at 1,000 feet," and led to the creation of an over-the-top design to combat the fires.

|

|

One of my earliest memories of following drag racing through magazines – how we all got started, right? – was a Letters to the Editor thread in Drag Racing USA about Funny Cars on fire. It was 1973, and there had been some nasty fires the previous year, including a particularly bad one for Butch Maas at the 1973 Gatornationals.

Funny Car fires were becoming a bit of an epidemic, and NHRA had responded in various ways with beefed-up requirements on driver suits and fire bottles, but a few began to address the issue from a different angle, reasoning that removing the flaming fiberglass body was key to improving safety. The idea seemed perfect. Get rid of the most flammable and longest-burning item of the car to reduce the driver’s exposure to the flames and at the same time improve driver vision.

Ideas poured in each month, with suggestions about ways to safely jettison the body and how to control it after its removal.

Most of the ideas were impractical and quickly forgotten, but some 20 years later, the idea resurfaced from the fertile mind of John Force, who seemed to perpetually be on fire in the early 1990s. After catching fire, spinning out, and rolling over at the 1992 Memphis, Tenn., event – which inspired his immortal “I saw Elvis at 1,000 feet” quote – Force had had enough and set out with crew chief Austin Coil to build one of the most gadget-laden floppers in history, a car that he expected would change the way people looked at Funny Car fires.

I mentioned this car in my recent 30th anniversary column, and a few of you begged for details and photos, so here we are.

When word of Force’s plan reached the National DRAGSTER offices, I was granted rare permission for an unbudgeted trip to Noble, Okla., to check it out. Force had gotten himself booked into a four-car match race there during the track’s Division 4 Lucas Oil Series event, which also was hosting the first National DRAGSTER Alcohol Showdown bonus event, so there were deemed enough good reasons for me to be there.

Force admitted that the car was a knee-jerk reaction to the Memphis crash, where the fire not only consumed the body but also took out the rear tires, sending him into a flat spin in the guardrail in the shutdown area. He finally slid to a stop in the sand trap, tipping over as he entered it sideways.

Force, who had just won his first two championships in 1990 and 1991, told me then, “Two years ago, I was like a crazy kid. A lot has changed mentally. You get a little older, you start looking at your kids, and you think, ‘What can I do to help myself?’ All of a sudden, at 43 years old, I’m starting to think, 'Y’know, I want to be around to enjoy being world champ.’ ”

Among the secondary additions were aluminum shields on the butterfly steering wheel – the precursor to today’s “doghouses” that shield the driver’s hands on the steering wheel – and a fire-extinguisher activation button on the brake handle. For years, the fire extinguishers were activated by a lever on the brake handle, which required the driver to open his hand to squeeze. “If you miss the handle, you don’t want to let go of the brake to regrab; it’s just instinct," Force reasoned. With the button, the driver would never have to let go of the brake handle.

A spring-loaded “positive action” parachute release was mounted on the inside of the car’s roof with a 6-inch silver button as the trigger. All Force would have to do was “slug it once” to activate the chutes. The old method relied on handles that had to be pushed or pulled far enough to release the chutes, and the driver was never sure if he had moved them far enough. The new design was either on or off and visible to the driver.

McKinney also mounted a pair of 6-inch aluminum billet wheels to the underside of the chassis to give the car better directional stability in case of a tire failure. Instead of the chassis dropping down onto the track, it theoretically could roll on the aluminum wheels.

Pushing the button began an air-activated two-step process that first unlatched the body at the front, then -- using tall air cylinders mounted vertically by the front wheels that fit into cups molded inside the body -- lifted the body about a foot off the chassis. The theory was that once the body was raised high enough, onrushing air would peel it from the chassis.

The body was tethered to the chassis by a 20-foot-long steel aircraft cable and was attached to a third parachute tucked under the body in the area behind the cockpit just in case the primary outside chutes had burned off.

The car only ran in that configuration in Noble and was never put to the test. I asked Force yesterday whatever became of the project, and he said that NHRA wasn’t thrilled with the whole body-ejection idea and shut it down but that some elements of the things designed on that car remain a part of cars today – chassis skid plates have replaced those wheels, but they’re mandatory now -- and other elements were obsoleted by automatic systems made mandatory by NHRA.

Typically, Force was on his way to a meeting and begged forgiveness for not having his head in the interview but recommended that I get the details from Robert Hight.

The Leahy system is perhaps the biggest and most crucial change in what a Funny Car driver does in a fire, in that it’s an all-in-one, fire-and-forget system. Once the driver activates the fire bottles, it simultaneously shuts off the ignition and the fuel supply and deploys the parachute.

“There were a lot of schools of thought back in the old days,” said Hight. “Should you hit the fire bottles first to put out the fire, then hit the chutes, so maybe the chutes don’t burn off? But, by that time, you’ve also covered a lot of [shutdown] territory. Or should you hit the chutes first – with the chance of them burning off – and then hit the fire bottles? There wasn’t a right or wrong way, but this way, it all happens at once.”

Additionally, on any blower backfire that pops the pressure-sensitive manifold burst panel, the ignition and fuel are automatically shut off – with no driver intervention necessary -- and the chutes deployed.

In the 20 years since, NHRA-mandated rules have been implemented to further enhance driver safety, including ballistic blankets and diapers, mandatory fresh-air systems plumbed to helmets, shielded parachute cables, head and neck restraints, roll-cage shrouds, carbon-fiber brakes, and shutoff controller, to name but a few. In the 1992 Rulebook, the Funny Car section had five pages; the 2012 version fills 13 pages.

“With the diapers we have today, the whole mess and fire can be contained in the bag and never gets onto anything,” he added. “I kicked two rods last weekend in Englishtown, and we had no oil that got out.”

Hight also pointed out that today’s synthetic oils have a higher flash point and that header coatings have made a huge difference, but the body coating – applied to the underside of all bodies and mandatory under NHRA rules – was a game changer.

“John had a fire the other day, and there were flames coming out of the wheelwells and around the headers, but the body suffered zero damage,” said Hight. “He ran it the next run. It was unbelievable. We’ve never had it so good.”