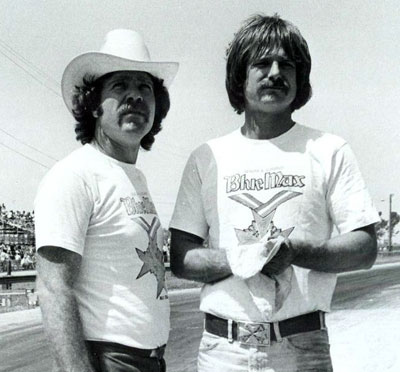

Flying high: Harry Schmidt and the Blue Max

Harry Schmidt, right, with Raymond Beadle

(RayMar photo; Marc Bruederle collection) |

Surprise. Bet you didn’t expect to see me this week, let alone on Thursday. Then again, I didn’t expect us to lose another great name from our sport earlier this week, and even though I told you I’d be incommunicado during this time -- traveling to both the Houston (last weekend) and Atlanta (starting today) events -- I couldn’t let another day go by without writing about the passing of Harry Schmidt, the original owner of the famed Blue Max Funny Car.

We had just landed in Dallas Monday on the way home from Houston, and, checking my email on my phone, I saw the sad message from Fred Miller, a key member of the mid-1970s Blue Max posse, that the 67-year-old Schmidt had died earlier that morning after a battle with cancer. Within a few minutes, former Blue Max pilot Richard Tharp was lighting up my cellphone to also make sure I knew.

Raymond Beadle, of course, made the Blue Max a household name with his legendary battles with Don Prudhomme in the mid-1970s and the three consecutive world championships that followed, but it was Schmidt who gave the sport the Blue Max Funny Car.

Two years ago in National DRAGSTER, I wrote a history of the Blue Max that I was going to repurpose here, but I also received an exhaustive history from Dave Densmore, a longtime friend and adviser to and confidant of Texas fuel racers in the last five decades and a good pal of Beadle's, who asked for Densmore's help in memorializing Schmidt, so below is the combined effort of our toils. I also talked to Beadle and Tharp yesterday and had further email correspondence with Miller.

The Blue Max was not Schmidt’s first car, and he had been crew chief for fellow Texan ”Big Mike” Burkhart’s Funny Cars in 1966 and 1967, first on an injected, nitro-burning ‘66 Chevy II, then a ‘67 Camaro.

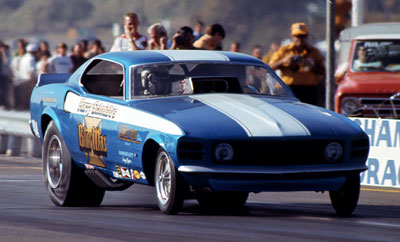

The first Blue Max Mustang, with Jake Johnston at the wheel at the 1970 NHRA Springnationals at Dallas Int'l Motor Speedway

|

After sitting out 1968, Schmidt commissioned Don Hardy to build him a Ford Mustang for 1969 and added a potent powerplant prepared by the famed Ramchargers. The car carried only his name on its flanks, and both Paul Gordon and Mart Higgenbotham drove the car on an interim basis until Schmidt lured the talented Jake Johnston, then crew chief for Gene Snow, to drive the car.

It wasn’t until later that year that Schmidt gave the car, which already was painted blue, its famous Blue Max appellation after seeing the film of the same name.

“I guess it was that fall that I saw [the movie], and I thought that the name had a nice ring to it,” recalled Schmidt in a previous interview. “I loved that emblem, and since I had a German last name and my Mustang was blue, I decided that’s what we’d call the car when we started the ’70 season.”

|

The car was emblazoned with an image on its flanks of the pour le mérite (“for merit”) emblem (a blue-enameled Maltese cross with eagles between the arms of the cross that was known informally during World War I as “the Blue Max” and was the Kingdom of Prussia’s highest military order until the end of the war), and the Blue Max became arguably one of the most famous Funny Car names in the sport’s history, rivaled perhaps only by the Chi-Town Hustler.

The Blue Max made its debut at the 1970 Winternationals and set top speed at 203.61 mph. The team scored its biggest win at the end of the season, capturing top honors at the famed Manufacturers Meet at Orange County Int’l Raceway, where Johnston ran the lowest elapsed time in class history, 6.72, and, in the final, beat Rich Siroonian in “Big John” Mazmanian’s Barracuda on a holeshot, 6.89 to 6.88.

After Johnston and Schmidt had a falling-out and Snow wooed Johnston back to drive his second car, Tharp jumped at the chance to drive the car and made his Funny Car debut at the wheel of the Blue Max at that year’s inaugural Supernationals at Ontario Motor Speedway – where he also was piloting his regular ride, the Creitz & Donovan Top Fueler -- and drove the car until mid-1973. The team won the 1971 IHRA Winternationals and a number of other IHRA crowns but only ran a limited NHRA schedule.

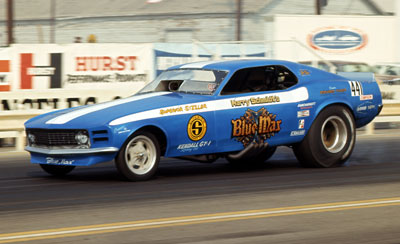

Richard Tharp took over the butterfly of the Blue Max at the end of the 1971 season and drove it through the end of 1973.

|

“Harry was a very special individual,” remembered Tharp fondly. “He was very smart and way ahead of his time. He was the first one to put a quick-change [rear end] in a Funny Car and the first to run a big fuel pump and hang a lot of weight on the clutch. We didn’t really know why we were doing it at the time, but it worked. At the time, we had one of the cars to beat. There was us, the Ramchargers, ‘Snake’ [Don Prudhomme], and ‘Goose’ [Tom McEwen], and ‘Jungle’ [Jim Liberman] and [the] Chi-Town [Hustler].”

The team ran close to 100 dates in 1972 -- including seven in one crazy six-day stretch — but the touring finally got to Schmidt, who parked the car but didn’t disappear entirely from the scene. An ambitious young Texan from Lubbock named Raymond Beadle, a former Top Fuel racer, was beginning to make a name for himself as the driver of Don Schumacher’s second Funny Car, and Schmidt joined him on the road in the summer of 1974 working on the car.

“I had known Harry for a long time and hired him to help me work on Schumacher’s car,” Beadle reminisced with me yesterday. “I was paying Schumacher a percentage to run the car – 20 percent off the top – but he was making more than I was, so I asked Harry if he might want to partner with me and bring back the Blue Max.”

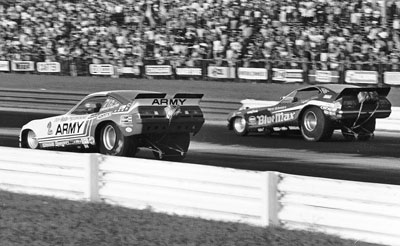

The Blue Max was one of the hardest-charging Funny Cars of the mid-1970s and the second to record a five-second pass. |

One of the greatest moments of the Schmidt/Beadle partnership was their victory over Don Prudhomme in the final round of the 1975 U.S. Nationals, where they also set the national record. It was Beadle's first NHRA win.

|

Schmidt, far left, Beadle, "Waterbed Fred" Miller, and crew basked in the glory of their U.S. Nationals triumph.

|

The duo started together in 1975, and Beadle drove the Blue Max Mustang II to their first NHRA victory at the prestigious U.S. Nationals, handing Prudhomme and his vaunted Army Monza one of only two losses that season. In late 1976, Beadle bought out Schmidt’s interest in the car, though Schmidt continued to work on the car before leaving the team in 1978. Though he did win the IHRA championship in 1975 and 1976, other than the non-points-earning inaugural Cajun Nationals, where he beat his future crew chief, Dale Emery, in the final, Beadle didn’t win again on the NHRA tour until the World Finals in Ontario, Calif., in 1978, two months after Beadle became the second member of the famed Cragar Five-Second Club. When Schmidt left, Beadle hired Emery.

“He was a real good guy, very detail-oriented,” Beadle remembered of Schmidt. “And he was very smart. The air jacks that all the teams use today, he and Pat Foster and Jim Hume built one just like them, but it was hand-operated. And the big tool trays that all the teams use? Harry was the first one to ever build one of those, and one of the first guys to want to run the big magnetos and bigger fuel pumps and dual plugs. Partnering with him back in 1975 was a turning point for me. We were successful from the start, and that led to a lot of other things, even after he got out.”

"He taught me a lot,” remembered Miller, who was hired by Schmidt and even lived with him for a couple of years. “He was bright and wanted things to be first-class. The first day I went to work for him, he told me that if I ever had a problem and could not figure it out, that I should ask Austin Coil. Harry said that Austin would not blow smoke up your ass. If he liked you, no problem. I will always remember that. Also, Dale Emery always admired Harry. Enough said!”

After he left drag racing, Schmidt became a jewelry wholesaler in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. He retired three years ago and played golf and traveled extensively and remained close friends with Beadle. He was diagnosed with cancer about a year ago and thought he had beaten it, but it returned and this time claimed his life.

“I had called him a few times in the last few days, and he never answered, so I drove out to his house,” said Beadle. “He was already in hospice care. He opened his eyes when I walked in, and I talked to him for a little while. He tried to talk to me, but I couldn’t understand what he said, but he held my hand, and that was it. I knew he was going to be gone.”

Tharp had already been to try to see Schmidt, but when he heard of his deteriorating condition, he couldn’t bring himself to see his old friend in such a grave state. He and Beadle, joined by other luminaries of the 1970s, including Prudhomme and Ed Pink, who are flying in from California, will be at Schmidt’s services later this week to pay their respects.

“He was just a great guy,” said Tharp. “Ask anyone. Everybody loved Harry Schmidt. He didn’t have any enemies or cross words with anyone. Just a great, great guy.”

Schmidt may have left us, but the legacy he left and the name of the famed Blue Max will ride high in the skies of drag racing history forever.