Dale Emery: A life of Pure Hell, wild rides, and big wins

Race fans are accustomed to seeing Funny Cars pointed every which way on the dragstrip. When they’re not pointed toward the finish line, they can be found zigzagging around their lane (and sometimes the other). We’ve seen them bank off of guardrails, fly through the air, and even wind up pointed the wrong way up the track.

Race fans are accustomed to seeing Funny Cars pointed every which way on the dragstrip. When they’re not pointed toward the finish line, they can be found zigzagging around their lane (and sometimes the other). We’ve seen them bank off of guardrails, fly through the air, and even wind up pointed the wrong way up the track.

But only once have we seen a Funny Car doing a nose stand at three-quarter-track. This is that story and, behind that, the story behind the guy who rode out that terrifying tip-over at the 1977 U.S. Nationals.

Long before he saddled up behind the wheel of “Big Mike” Burkhart’s silver Camaro that fateful Friday in Indy, Dale Emery was no stranger to wild rides. He had come to national attention and fan-favorite status in six years behind the wheel of Rich Guasco’s spectacularly unpredictable but wildly fast Pure Hell fuel altered and won a pair of NHRA national events in the mid-1970s and been on his head a few other times, including in an ill-fated stint as a wheelstander driver.

I was finally able to track down Emery last week to get the story of that crash as well as his memories of an action-packed and highlight-filled career in fuel racing.

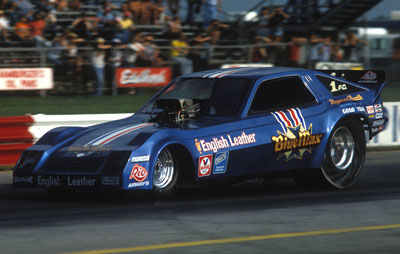

As you can see in the Larry VanSickle photo above and in the somewhat grainy video at right, Emery’s ride was a white-knuckler as it hit the guardrail, stood on its nose, then barrel-rolled down the guardrail’s knife edge. In retrospect, it’s surprising that his only injury was a small broken bone in his left arm. Running alongside Raymond Beadle’s Blue Max and attempting to better his opening pass of 6.22, 234.98, things quickly went bad for Emery.

“When it left, it was carrying the front wheels, and it kept going over towards the center,” he remembered vividly. “I kept turning the wheel, and when I finally lifted, the wheels were still turned, and it shot over to the other side [toward the guardrail]. I whipped it back and thought I’d saved it, but then the rear wheel hit the guardrail and just threw it right straight up in the air.

“Looking down at the track, I was thinking, ‘This is going to be bad.’ After it hit, it rolled down the guardrail a couple of times, and they had to cut the cage off to get me out. I knew that I’d hurt my arm but didn’t know then why.”

(The squeamish out there may well want to skip this part.)

The NHRA medical crew tended to Dale Emery, who suffered a broken bone in his arm but was back at the track the next day, sharing his tale with Dale Armstrong.

|

|

“What had happened was that the fuel-shutoff lever went through my firesuit and stabbed into my arm through the skin and cracked the bone up near my wrist,” he said, then, perhaps sensing me mentally retching at the thought, added nonchalantly, “Aw, it wasn’t much. That was the only thing that happened.”

Emery’s 6.22 held up to make the field in the No. 13 spot (there’s that number again), but it was clear that he wouldn’t be racing come Monday, or anytime soon for that matter. Although the crash did turn out to be the last ride of Emery’s wonderful driving career, he hadn’t made that decision at that point.

Emery was at the track the next day in an overkill cast, and Beadle, who was struggling performance wise and just winding down his partnership with Harry Schmidt, offered Emery the job tuning the Max. Emery did not immediately jump at the offer.

“Raymond was getting ready to take the Blue Max to England for the first time, so I told him I wanted to think about it for a while and to talk to Burkart,” said Emery. “Crashing didn’t bother me, and I figured that I would drive again, but I took a couple of weeks to think it over. I’d never tuned for anyone other than myself, but since I couldn’t do much else with a broken arm, I figured I should try it."

To sweeten the offer, Beadle told Emery that he could fill in for him behind the wheel of the Max on occasion, when Beadle’s other plans precluded him from driving.

“There were a few chances for me to do that, but after standing on the outside of the car, I thought I could learn more there than driving it,” he said. “I never drove again and really got into the tuning deal.”

Emery's first year with the Max, 1978, was fraught with frustration.

|

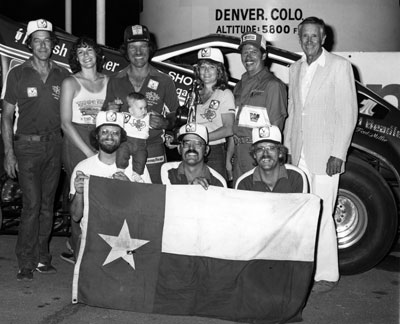

By 1980, the team was winning regularly, including in the thin air at the Mile-High Nationals. Emery is at the far left in the back row.

|

Emery tuned Raymond Beadle to his second Indy win, at the 1981 event.

|

Although they would go on to win the world championship three straight seasons (1979-81), finally wresting the crown from Don Prudhomme’s head, success was not immediate for the new partners. They struggled mightily in 1978 and didn’t even crack the top 10 as Beadle had done the previous three seasons.

“We had a fuel-tank problem that lasted nine months,” he recalled, frustration still evident in the recollection. “We couldn’t even do a burnout without killing it. Turns out there was a problem with the vent on the fuel tank. Once we found that, we had a new tank made. The first race was the 32 Funny Car deal in Seattle, and we won that race, went to Boise and won that deal, went to Kansas City and won there, then we went to Indy and ran our first five. It just sorta came together; we had everything; it just wasn't working right.”

(Beadle’s 5.98, Aug. 30, 1978, during qualifying in Indy, made him just the second Funny Car driver to run in the fives and came nearly three years after Prudhomme became the first to run in the fives, Oct. 12, 1975, at the World Finals at Ontario Motor Speedway. That’s how far ahead of the pack Prudhomme was during his glory days.)

They closed 1978 with their first win as a team by winning the World Finals with a final-round defeat of Tom McEwen (who, as you will read in a bit, had shared another interesting final-round pairing with Emery five years earlier).

After runner-ups at the 1979 Winternationals, Springnationals, and Mile-High Nationals, the Max found the winner’s circle again at the Summernationals and the Fallnationals and finished as world champ, eking past Prudhomme by just 531 points, less than three rounds worth of racing.

The famed Blue Max crew, which also included “Waterbed Fred” Miller and Dee Gantt – both of whom had histories with Emery – scored three wins and two runner-ups in 1980 to win its second straight championship, this time by a landslide 1,751 points over second-place Billy Meyer, and added a third crown in 1981, which included a triumphant win at the U.S. Nationals.

I asked Emery how the team maintained its championship ranking for three seasons.

“I just liked to try a lot of things,” he said. “I was the only who came up with the dual-mag drive – not that the idea was brand-new; some early, early cars had them – but we were the first to really make it work. I was also the first one to have down nozzles in the heads. It was just about trying things to stay on top, to make it run quicker. You have to keep trying things; you think you’re going to be king forever, but you’re not.”

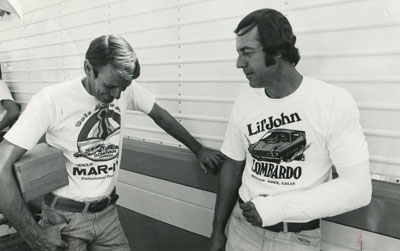

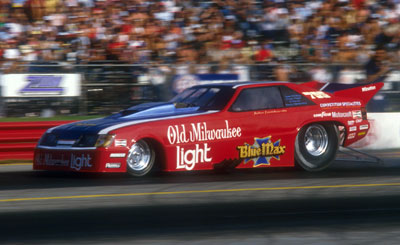

Emery tuned the John Lombardo-driven red Blue Max to Indy glory in 1985, but the Max's glory years were coming to an end.

|

Emery would win Indy again in 1985 with Lil John Lombardo driving the Max, but victories were becoming few and far between as Beadle’s burgeoning NASCAR team began to take his attention and his dollars. Emery rode it out with the team through those lean years, which finished with Richard Tharp and Ronnie Young behind the wheel of cars probably not worthy of carrying the Blue Max name.

“We couldn’t hardly buy parts; I told Raymond that he needed to sell the car while it still had a good name, so that’s what he ended up doing in 1990,” said Emery, who quickly turned his skills into a business with Dale Emery Fuel Systems, building fuel pumps and injectors for the burgeoning nostalgia movement as well as for a few contemporary teams, and resumed his crew chief ways. Among his clients is the recently resurrected Blue Max nostalgia flopper, driven by Young, bringing Emery back full circle with the famous team.

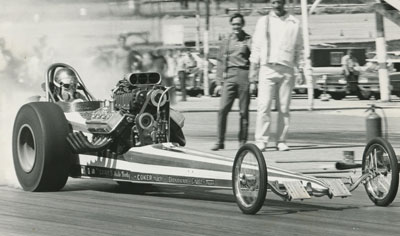

Emery became nationally famous after teaming with Rich Guasco in 1965 to drive his Pure Hell fuel altered.

|

The Pure Hell was not only one of the wildest of the breed but also the fastest.

|

Emery ended up upside down in a water-filled ditch at Fremont Raceway when the steering wheel came off in his hands.

|

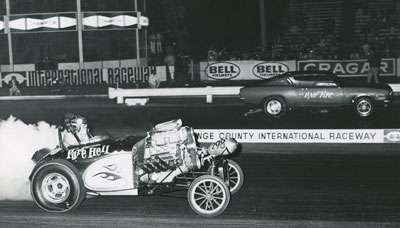

Emery and the Pure Hell also tackled -- and beat -- Funny Cars.

|

Although Emery is most widely associated with Texas, he actually was born in Stillwater, Okla., and grew up in Northern California after his family moved there when he was 5. He began his racing career in 1955 with a C/Gas ‘41 Chevy coupe and graduated to a rear-engine fuel coupe in 1959, then a gas dragster in 1960 and, finally, a Top Fuel car with partner Woody Parker in 1962. It was through the Parker car that Emery met Pete Ogden, who had built Emery’s Top Fuel car and the famed Pure Hell fuel altered for Guasco.

Emery took over the controls of the famed fuel altered from Don Petrich in 1965 and drove it for five seasons of wild wheelstands, sideways passes, and off-track excursions, becoming known as one of the class’ finest and fearless wheelmen, which made the Pure Hell a popular match race attraction; his battles with friend “Wild Willie” Borsch for class supremacy kept the fans enthralled.

“I think because we had the engine so high up is why it did those wheelstands, but as long as the tires were lit, it was easy to drive, but when the tires dried up, you’d better look out,” he noted.

The car, which sported an 89-inch wheelbase, originally was equipped with Chevy power and a primitive lockup clutch. “When it locked up at half-track, it was anybody’s guess which way it would go,” he told National DRAGSTER in a 1994 interview. “To my way of thinking, you just have to be well-coordinated to drive a Funny Car. But that altered, well … you just really had to work at it to keep it straight."

And it helped to have a working steering wheel, too, as Emery found out one day at Fremont Raceway, not far from his then home in Livermore, Calif.

“We used to have a Crossley steering box on the car, but they put a new P&S in it, and they told [Guasco] you had to pin the steering wheel, but he forgot. As soon as it took off, the steering wheel came back with my hands. It went off the right side of the track into the grass, but it had rained the night before, so it didn’t slow down when I pulled the brakes because the grass was still wet. It went into a ditch filled with water, dug in, and flipped it upside down.”

For a brief time, Emery was underwater, holding his breath, until the car was righted, which led to a scene “right out of The Three Stooges.

“I was still choking a little bit, and the ambulance guy was trying to pull my helmet off without even unstrapping it. Tony [Del Rio, a huge, badass wrestler who used to paint the car] smacked him and knocked him out in the water. I went to the hospital to get checked out, and the ambulance driver came in looking to see who knocked him out. I told him, ‘Don’t even start because he’ll finish it. …’ ”

Guasco also tagged Emery with his famous nickname “the Snail” for his laid-back nature. “He was kind of nervous, and I was always just hanging out. He used to say, ‘Look at him: He’s just like a snail; he never goes anywhere fast.’ ”

A Chrysler engine and a slipper clutch were added in 1968 and really paid off. Borsch was the first to top 200 mph with a 200.44-mph run at Irwindale Raceway Sept. 23, 1967, but the next year, Emery blasted to a 207.36-mph clocking while winning the Hot Rod Magazine Championships at Riverside Raceway, a speed that would not be bettered that year. A week before the Riverside win, the Pure Hell had dispatched a field of floppers at a Funny Car vs. Fuel Altered battle at Orange County Int’l Raceway.

“Driving the Pure Hell was the most fun of anything I ever did. There was no money to be made doing it, but we did it because we liked racing.”

The Pure Hell was heavily damaged in a highway accident near Deming, N.M., while Emery was on his way home to Dallas from the U.S. Nationals. The trailer blew a tire, and the rig ended up in a culvert. The car sat for a while as Guasco decided what came next (a Pure Hell Funny Car that, despite historic notations to the contrary, Emery insists he never drove).

|

After leaving the Pure Hell team, Emery sampled a long line of different rides. He drove the Rousin-O’Hare slingshot Top Fueler for six months in 1970 – winning the $1,000 Texas Bucks event at Dallas Int'l Motor Speedway – and later helped Gary Watson build the Flying Red Baron Mustang wheelstander, then crashed it not long after.

“I ended up rolling the thing over,” he said. “The converter for the automatic transmission was screwing up; it came down, landed sideways, and rolled over. He wanted me to help pay to get it rebuilt, but I told him I wasn’t interested in it that much to do that. Yeah, I tried it, but I didn’t like it; it was too much of a clown deal to me.”

Ironically, another wheelstander owner, Bob Riggle, of Hemi Under Glass fame, gave Emery his first Funny Car ride, an ex-Don Gay Pontiac Trans Am of the same name. After a time behind the wheel of that car, Emery went to work for Sam Harris at Chaparral trailers (which is where he first met Beadle, in 1974, who was driving for Don Schumacher at the time).

|

In 1973, Jeg Coughlin Sr. was looking to go Funny Car racing and hired Emery to drive. Gantt, who had met Emery while crewing for Borsch, was already working with Emery and joined the team, and Miller, who was helping to paint the new body, asked to go with the team to the PRO event in Tulsa, Okla., and stayed onboard.

In the span of just a year, Emery and the JEGS Camaro won two NHRA national events – the 1973 Grandnational in Canada and the 1974 Winternationals – and a couple of IHRA events and were runner-up at the 1973 NHRA Supernationals in Ontario, Calif., after what proved to be another signature Emery moment caught on film.

Which brings us back to the aforementioned previous final-round history with McEwen. McEwen, who, despite his match race and promotional prowess, had never won an NHRA national event, made the Supernationals field only as an alternate from the 17th spot when Bobby Rowe reported in broken. McEwen’s Carefree Duster dispatched Dave Condit, Jim Dunn, and Jim Nicoll with a 6.59 and a pair of 6.50s to reach the final.

The other semifinal pitted Emery against Prudhomme, with “the Snake” eager to beat Emery for a chance to take down his former teammate in a period when the two weren’t on the best of terms. Emery had already run 6.28 and Prudhomme 6.33, so the winner would be a heavy favorite against “the ‘Goose” in the final. Prudhomme didn’t make it down the track, slowing to a 13-second, 55-mph crawl, and watched Emery’s mount disintegrate before his eyes in the other lane, a massive blower explosion first removing the roof and then the rest of the body.

|

Don Gillespie’s great photo – which shows the fuel-tank lid blowing open; a rule was already in place for screw-in caps for 1974 – is only half the story.

“When we started it up for the run, the aluminum line that ran to the back of the injector was leaking at the ferrule,” he remembered. “I thought it would make it on down there, and I was going to click it off early, but it went bang before I could. It blew the body off, and I couldn’t see where I was going and clipped a hay bale in the shutdown area and flipped over. We didn’t have a spare body, so it wouldn’t have mattered if I crashed or not.”

McEwen singled for the win.

Jaime Sarte repaired the chassis and got the team a new body, and it opened 1974 with the aforementioned Winternationals win. The joy of that victory faded quickly when a pay dispute with Coughlin led Emery to quit the team and head back to work for Chaparral. Miller left to join the Blue Max team, and the two were reunited, with Gantt added to the fray, a few years later on the Max team.

Inbetween, Emery was tapped to showcase the Vega of former fuel altered pals Leroy Chadderton and Glen Okazaki that Ed Pink had shipped to England for Roy Phelps (owner of Santa Pod Raceway) and ran a 6.99, on fire, when a lifter broke. Famed wheelman Allan “Bootsie” Herridge later drove this car, which became one of Europe’s finest, under the Gladiator name.

|

Emery teamed with Burkart in 1976, and they were runner-up to Beadle at the inaugural Cajun Nationals. The car ran “good, not great,” according to Emery, “but we done good.”

They ran on-again, off-again on the NHRA national event scene in 1976-77 and almost always qualified and, freakishly enough, lost several times in the first round to McEwen. Prior to the Indy crash, the car suffered a fire in the first round at the Summernationals, but that was nothing compared to what happened a few months later in Indy.

So that’s the story of Dale Emery’s career, hardly lived at a snail’s pace. Thanks to Dale for his keen memories and Fred Miller for the assist, and thanks to you all for following along.