How the elephant crushed the guardrail

Even when you truly enjoy the subject matter, the reader response, and the thrill of telling a new story, writing a biweekly column can be tough. (I can’t imagine what I was thinking when I began this column more than four years ago as a thrice-weekly endeavor.) If this were my only job at NHRA, I could bust off two columns a week without breaking a sweat, but there’s this little weekly publication that we also produce – maybe you’ve heard of it -- that eats up time like a nitro engine gobbles fuel.

Most weeks, I have a good idea of what my topics will be for the next two columns, but other times, I veer off course like a flopper with a cylinder out when something else more urgent or interesting crops up, and off we go like an out-of-control simile express.

|

Sometimes I just never know where a column is going to come from, and today’s entry is a great example. While rummaging through the folder of black and white prints from the 1977 Springnationals searching for a photo of Bob Pickett racing Eddie Pauling to illustrate Friday’s column, I came across the peculiar photo at right. I had never seen it, and it definitely stopped me.

I’ve seen plenty of photos of race cars getting up close and personal with Mr. Guardrail, but never one of a car heading back to the starting line, an orientation that was made evident by the Valvoline scoreboard in the background and, oh, the fact that the car IN THE SAME LANE was going the other way.

My first thought was that this was one of those cases where the driver had no reverse and whop-whop-whopped the throttle to spin the car 180 degrees to get back to the starting line to make the run and somehow overcooked the last whop. I’ve seen that maneuver successfully executed a few times but never flubbed like this.

|

The car looked familiar – there weren’t a lot of those slant-nose ’77 Vegas around; most teams were using Monza, Arrow, or Horizon/Omni bodies – and I believed with some certainty that it was the Green Elephant. I trawled through the photo coverage of the event before spying the photo, which did in fact reveal the car to be the Green Elephant and the driver as future NHRA Top Fuel world champ Rob Bruins, but the caption didn’t explain the car’s unusual circumstances.

Fortunately for you (and me), I have a great relationship with Bruins, who has been the subject of quite a few items in my columns. I attached the photo to an email and asked the obvious question: “What the heck?”

I’m relatively certain that most of you only know of Bruins from his Top Fuel heroics – two wins, four runner-ups (including Indy 1978) and the 1979 world championship in Gaines Markley’s dragster – and didn’t realize that the pride of Bremerton, Wash., has a background in Funny Car, but it’s true.

When Bruins began driving Top Fuel in 1976, it was for Herm Petersen and Sam Fitz in their Olympia Beer-sponsored dragster. Petersen, horribly injured in a 1973 crash and fire at Orange County Int’l Raceway, hung up his helmet for good after a second crash, in 1976 in Calgary, Alta., and turned the reins over to young Bruins, who had been campaigning a BB/FC with partner Jim Wright after a couple of seasons in the saddle of a front-motored injected fuel car.

When Olympia ended its sponsorship with Petersen and Fitz at the end of the 1976 season, the dragster was parked, and at the same time, fellow Washingtonians Jim and Betty Green, who had won the Funny Car world championship in 1973 with Frank Hall and collected a Winternationals runner-up with Mike Miller in 1975, were back after sitting out the 1976 season and, more important, back with sponsorship from Bardahl. (You can read more about the Greens and their history in this 2008 column I wrote.)

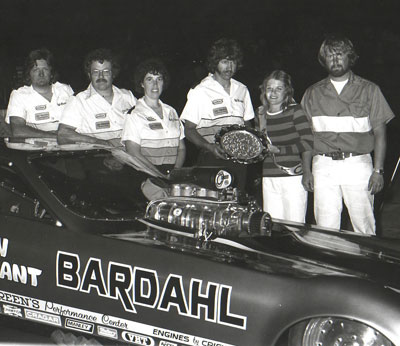

The Green Elephant team accepted a Best Appearing Crew award. That's Rob Bruins, third from right, next to the Greens and crewmember Dennis Taylor.

|

Just prior to the 1977 Winternationals, the Greens asked Bruins to drive their new car, so he quit his job at the shipyard and went full-time racing (“just like my heroes,” he noted), but success was not quick in coming.

“We won a Division 6 points meet (thanks to a ‘240 Gordie’ [Bonin] red-light) but other than that had very little success at major races but put on a good show at match-race-type stuff,” Bruins remembered. “Anyway, we were actually sneaking up on a raceable combination when we went to Columbus; prior to that, we were mostly just contenders for Best Appearing Car or Crew.

“At Columbus, the car came to life, and on our first qualifying run, I was side by side at half-track with the Hawaiian when the transmission blew up, spitting the reverser off the back. I remember thinking everything was feeling good when ‘Boom,’ I remember something was whacking me on my legs, and everything was red inside the car. It turns out the reverser lever was beating up my legs as it had detached itself from the two-speed case, and the red all over my goggles was the transmission oil. Of course, it also popped the blower off, broke the windshield, etc.

“The clutch and engine combo that was finally starting to work was using a 38 percent transmission. During the repair process, we put in a 30 percent transmission (because that's what we had), and that really screwed up our combination. The next two runs resulted in wheelstands where I shut the car off when I lost the horizon. Jim told me I had to learn to drive through those wheelstands, and there was some tension building. The next qualifying run (remember that back in 1977, you could make as many qualifying runs as you wanted) was side by side with Tom Hoover.

|

“Luckily, Tom made a long burnout because during my burnout, it felt like something locked up, and the rear tires just started skidding out past the Tree, and the car made this long lazy U-turn, putting me up against the guardrail in the opposite lane facing the starting line. As I sat there against the guardrail with the engine still running, Tom backed up by me, and when he got past me, he stopped and looked at me as if to ask ‘What are you doing?’ or something to that effect.

“We took the Elephant back to the pits and tore it completely apart looking for something that had broken. We couldn't find anything wrong other than the fiberglass damage on the front of the body. We put it all back together and got back in line for another qualifying attempt when it started to rain and washed out the rest of qualifying. The next day (race day), we set up our pit site to fulfill our sponsor commitments, and Jim asked me to take a walk with him. We walked out to the fence next to the track, and I expressed my lack of confidence and uneasiness in the car, and he said if I wasn't comfortable in the car, it was time for a change.”

Bruins agreed to stay with the team long enough to get the car repainted and engine and transmission race-ready again back in Washington and even offered to drive the car until the Greens could find a new shoe, but the Greens politely declined. (Richard Rogers became that new driver and promptly scored a runner-up finish behind Don Prudhomme at that year’s U.S. Nationals.)

1979 NHRA Top Fuel champ Bruins, left, with team owner Gaines Markley.

|

“When I got home to Bremerton, my sister had a list of people that had called to offer me various positions on other race teams,” Bruins continued. “Gaines Markley, who had always been helpful to me with my own stuff, had just had a machine-shop accident in which he had cut his hand severely and needed help with the maintenance on his car, so I immediately went to help him. A couple of days later, the Bubble-Up guys called and asked me to drive their new dragster to sort it out for Gordie. So I was wrenching Gaines' car and driving the Bubble-Up car for a couple of races until Gaines put me in his seat -- the rest, as they say, is history. [Read my column about their partnership here.] I was just glad I could keep racing and not have to go back to work at the shipyard in Bremerton.

“Driving the Funny Cars was fun from the burnout and dry-hop aspects, but back in those days, the fires were all too frequent. Just a couple of weeks ago, ‘Gentleman Hank’ Johnson and I were talking about that and how we enjoyed the showmanship involved with driving the Funny Cars but were never that excited about actually racing them. Every run in a Funny Car was like a single because you couldn't see your opponent; if you could see him, you were losing. In dragsters of that day, you had a full field of vision and could see your competition right next to you all the way down the track. There is nothing cooler than going 240 and seeing another pair of wire wheels right there next to you, hopefully just a little behind yours.”

Despite their unplanned parting 34 years ago, Bruins and the Greens remain friendly, sitting together at autograph-signing sessions in the Northwest (some of the Greens’ handout cards still include Bruins) and wheeling the Assassin Cacklefest dragster at a number of the push-start events in the Northwest and in Bakersfield.

So that’s the story of how the Elephant crushed the guardrail in Columbus. Thanks to Rob for sharing one of the probably less than memorable events of his career I’m off to Dallas on Thursday for the AAA Texas NHRA Fall Nationals at Texas Motorplex, so there won’t be a column Friday and perhaps not next Tuesday, depending on how everything goes with the week’s issue. Enjoy your weekend, and I’ll see you sometime next week.