Superman lives!

|

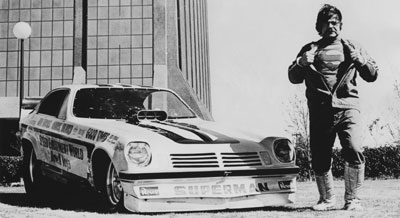

Long before John Force ever saddled up in his first Funny Car, drag racing had another gregarious character that we all called “Superman,” a tough-as-nails nitro jockey who piloted fuel dragsters and Funny Cars in a 20-plus-year career.

His name is Jim Nicoll, and it’s a name familiar to any hard-core drag racing fan and a name that surfaces every time the Mac Tools U.S. Nationals rolls around on the racing calendar because he was involved in one of the hallowed event’s most spectacular moments, a scary clutch explosion and crash alongside Don Prudhomme in the Top Fuel final in 1970.

I recently had a chance to catch up with Nicoll to talk about his racing career in general and, of course, that unforgettable final in particular.

Nicoll has long since retired from the cockpit and today manages a Mexican resort, the Desert Oasis, in Puerto Penasco (Rocky Point) on the

Contrary to popular lore, Nicoll did not earn his "Superman" sobriquet for walking away unhurt from nasty crashes (though it's certainly supported in an ex-post-facto kind of way). Instead, the nickname was hung on him by former NHRA Vice President

“Ronnie Martin and I were up in Irwindale for the races, and we were off shooting pool, and I got into a fight with two or three guys and whipped ‘em,” Nicoll recalled nonchalantly. “The next day, Gibbs started calling me ‘Superman.’ “

“That’s basically the story,” attested Gibbs. “He was one tough little son of a bitch and did not avoid trouble.”

Before he burst onto the racing scene and long before he made grown men blanch and women cover their eyes in horror when his Indy wreck was broadcast to the nation on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, Nicoll raced jalopies as a teenager and, at 17, had a flathead-powered '32 Ford coupe before graduating to a Jr. Fueler and then a blown gas dragster.

Born in San Antonio, Nicoll moved to Southern California in the 1950s to be near the hotbed of racing action and was a regular at all of the famous SoCal tracks as well as places like Holtville, Colton, and Riverside. As his reputation as a fearless wheelman grew, so did the list of those seeking his skills, which in 1962 also included Top Fuel.

“I drove for Pat Atkins, Ronnie Martin, Marv Rifchin, the Syndicate of Jack Raitt, Red Mendocino, Leonard Abbott, Ray Schultz … a bunch of them,” he recalled. “Leonard Abbott, who founded Lenco transmissions, had a speed shop in

“I ran a lot of test stuff in my career for clutch and tire companies,” he continued. “When Mickey Thompson was trying to build aluminum heads for the 392 when I was driving for Pat Atkins, I used to get my hair burned off every weekend. When they’d get hot, the guides would swell up and hang open the intake valve and blow the blower off.”

|

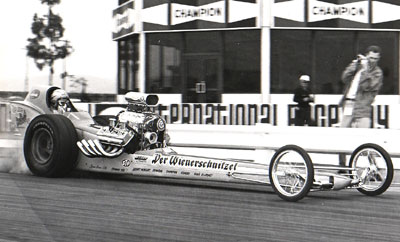

Nicoll probably received his first national attention in 1967, when he obtained one of drag racing’s first non-automotive sponsorships, the backing of fast-food giant Der Wienerschnitzel, and went on tour. The next two years, he fielded a pair of Der Wienerschnitzel Top Fuelers, one driven by him and the other by Leroy Goldstein.

“I actually had first tried to get a deal with Jack in the Box because my shop in

“We’d crank it up at the stores and take hot dogs with us to the races,” he recalled. “I ate more damn hot dogs than you could believe. The deal lasted for a couple of years, but they were having some financial problems, so [the corporation] gave me a Fryer Fish sponsorship instead, but it didn’t last long.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nicoll still was a highly respected independent by the time the 1970 U.S. Nationals rolled around and his date with destiny loomed. It had already been a frustrating season for Nicoll, who had reached the final at the Springnationals in

Prudhomme had worked his way to the final with a close but nonetheless gratifying 6.62 to 6.66 first-round conquest of rival "TV Tommy" Ivo, then followed with a strong 6.43 victory over Danny Ongais’ game 6.49. “The Snake” followed with an early-shutoff 6.45 to demolish Robinson's 6.64, then advanced easily to the final on a red-light by the surprise No. 1 qualifier, class rookie Brian Budd, who had piloted John Dearmore's machine to a 6.49 for the No. 1 spot.

Nicoll, meanwhile, had ripped his way past Jim Walther, Gerry Glenn, and Marshall Love with runs of 6.57, 6.60, and 6.59, then took a soft run into the final after Indy giant Don Garlits inexplicably fouled away a strong 6.58.

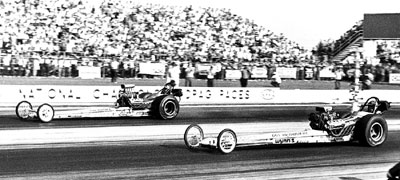

Prudhomme’s 426-powered Wynn’s Winder saddled up in the left lane and Nicoll’s 392-motivated digger in the right. They launched together, and it was obvious that Nicoll had found the tune-up as they stayed locked together the length of the quarter-mile. Prudhomme’s yellow rail tripped the win light for a narrow 6.45, 230.76 to 6.48, 225.56 victory.

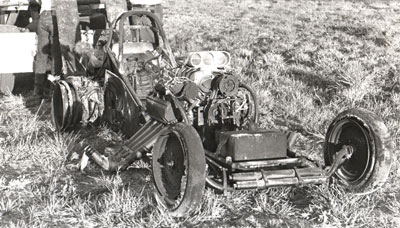

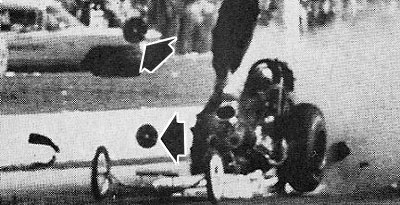

But just as they hit the win stripe, the clutch in Nicoll’s car let loose and cut the car in two right at his feet. The front half of the dragster, including the engine, slid in front of Prudhomme, who safely had the laundry out, and lazily and eerily scraped along minus its driver in front of a horrified “Snake,” who, thinking Nicoll had been killed, famously was captured by the Wide World of Sports microphones saying he was ready to quit.

Fortunately for Nicoll, his parachute had already begun to blossom when the clutch blew and helped slow the intact cockpit as it bounced over the guardrail and into the soft

“I remember everything but the actual crash,” recalled Nicoll. “I remember doing the burnout, and it seemed like the clutch wasn’t acting right. When I left the starting line, everything was cool, and we were side by side, and about 1,000 foot, I felt the clutch start to slip. The last thing I remember was reaching over and putting my hand on the parachute handle just in case, but that probably saved my bacon.

“I remember waking up in the ambulance and then went out again and woke up in the hospital. I had a concussion, and my right foot was swelled up. They’d cut my firesuit off me, so I just left in one of those damn gowns with my ass hanging out. I went to the hotel and then to the banquet that night. When I saw the footage, I was surprised how bad it had been; I had no clue.”

(Here’s a link to some YouTube footage from Diamond P’s Decade of Thrills tape, with Steve Evans and “the Snake” talking about the incredible footage.)

Nicoll also suffered a black eye, and within a week, he had Lester Guillory build him a new car in

Nicoll still was voted Drag News Top Fuel Driver of the Year and moved to Dallas right after the crash in Indy. He had a rear-engine car built (driven first by Billy Tidwell, then by Nicoll), but he already really had his eyes set on the increasingly popular Funny Car class.

At the end of the 1972 season, he switched to Funny Cars, partnering with Chuck Tanko, owner of Texas-based Speed Equipment World. Their first car was the Barry Setzer Vega formerly driven by Pat Foster. After the company went bankrupt, Nicoll ran under his own name, culminating in 1976 with the Good Times Monza.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Though Nicoll found some success on the NHRA circuit, he never reached another NHRA final and lived up to the "Superman" nickname with a series of nasty outings.

“I crashed a lot of cars at a lot of places,” he said. “I had worse crashes than the Indy one; they just weren’t caught on TV. I crashed at Cordova in my Funny Car one time when I blew a tire and did some endos in the lights; that was pretty horrible.”

One of Nicoll’s misfortunes led directly to a major safety improvement in Funny Car racing that is still used today: double-wall headers.

“I burned the Speed Equipment World car to the ground in

“We went to

The racing end came rather ingloriously for "Superman," as it has for many, and his kryptonite was financing, not to mention a healthy dose of additional bad luck.

“By 1976, I was beat up and couldn’t find a big-dollar sponsor,” he said. "I had everything going, but then Tanko bellyed up and my rig got stolen, and I didn’t have insurance. We were getting ready to go to E-town and had the car all loaded up, and we all went home to clean up, got back at 3 in the morning, and it was gone. We never found a thing.

“I loved racing, and I loved Funny Car and Top Fuel, both the front-motored cars and the back-motored cars, but I’d probably have to say I enjoyed the dragsters more because they went the fastest. I consider myself one of the pioneers of the sport because I was involved in a lot of the early things, and now I’m just taking it easy.”

According to Nicoll, he first went south of the border to help organize sand and off-road races near the resort “and ended up running the damn place. I came to visit a friend for a weekend and have been here for three years.

“It’s a beautiful resort,” he said. “We’ve got some beautiful condos and beach rentals, and I’m staying busy trying to write a book, and I like to keep up with the racing, but the computer system down here leaves a little to be desired.”

Nicoll has been to the California Hot Rod Reunion, back in his element among loud-talking friends and good company from the past, where his name can be joyfully placed with those of legendary hell-raisers of past years, guys like Goldstein, “Jungle Jim” Liberman, Richard Tharp, John “Tarzan” Austin, Dale Funk, Chip Woodall, Dave Settles, “Diamond Jim” Annin, and others.

"Superman" may have hung up his cape 30 years ago, but his superhero legend lives on.