Leonard Harris, drag racing's shooting star

|

|

|

|

A shooting star blazes its way across the sky in a spectacular but short-lived burst of glory, and that's an apt metaphor for the all-too-short drag racing career of Leonard Harris. He may well be the best driver you've never really heard of.

In a short six-month span, Harris, a filling-station owner from Playa del Rey, on the shores of the Pacific west of Los Angeles, went from a relatively unknown racer to being an NHRA Nationals champ and earning a still-standing regard as one of the best race car drivers in the sport's history.

In researching this article and interviewing the many principals, I was amazed at their genuine admiration for a man whose time on the NHRA stage was so brief but, like that shooting star, so intense.

From the time he partnered with engine wiz Gene Adams and chassis builder Ronnie Scrima in April 1960 until his tragic death at Lions Drag Strip, just six months had been stripped from the calendar, but they'd all fallen directly into the history books.

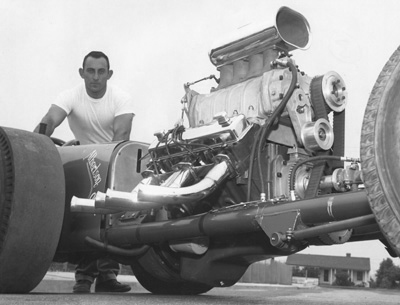

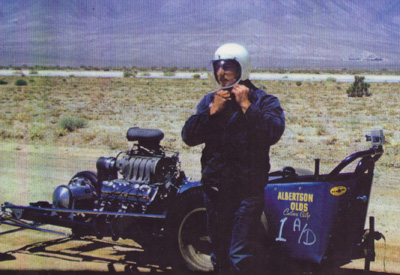

At the wheel of the team's famed Albertson Olds dragster, the group was all but unbeatable, a testament in part to the power that

There was never any question that the old master Adams, initially an aircraft mechanic by trade who started out by hot rodding his dad's '50 Olds 88 at the Santa Ana Drags in 1952, could make power. His trademark Oldsmobile engines were widely acknowledged as the best in the business, and after just a handful of years in the sport, he'd enjoyed success with Olds entries that dominated the coupe and sedan classes at SoCal tracks such as Santa Ana and Saugus – and even set a B/Gas national record of 111.24 at the 1957 Nationals in Oklahoma City -- in the years before meeting Harris and certainly in the years after Harris' passing, but there's also little doubt that Harris brought his own magic to the combination.

The partnership that developed between Harris, Adams, and Scrima was a combination of coincidence and a harmonic convergence of hot rodding forces in Culver City, home to the burgeoning hot rod industry with shops such as Isky and Edelbrock and a dedicated and savvy group of hot rodders that included the likes of future Freight Train engineers John Peters and Nye Frank, Mike Sorokin, "Jazzy Jim" Nelson, Craig Breedlove, Hank Bender, Ron Hier, Bill Adair, Walt Stevens, Frank "Root Beer" Hedges, Mickey Brown, Ed Weddle, and more.

While Adams was serving a two-year stint in the Army in the late 1950s, Scrima partnered with Mort Smith – with whom he worked at Engle Cams --- and Adams' brother, Gary, using one of Adams' Olds engines in a dragster, initially one that Scrima had built but more notably in one of Scotty Fenn's iconic TE-440 chassis. Scrima had worked with Adams before, most notably on a trip to the 1957 Nationals, and although

"Ronnie was a dragster guy, and he was interested in the Olds engine, so when I got drafted, I told him he could use my engine Olds in his dragster," recalled

As was sometimes the case in those early years, the going wasn't always easy and the cost not always cheap. Brown substituted for Smith on a fateful Sept. 12 night in 1959 at Lions and was killed in the car when it overturned.

|

|

|

When Adams got out of the Army in January 1960, he returned to his old haunts, which in

"Everybody had Oldsmobiles, and Albertson was the place everyone went to get their parts; that's where I met Leonard one day while getting parts for my engines," said

And he also knew Harris, who owned a

Adams and Scrima had purchased a K-88 chassis from Fenn, and while Scrima was modifying its design – much to the displeasure of Fenn – Adams, at Farr's suggestion, agreed to drop his 407-cid Olds engine into Harris' Fiat. The car, dubbed Lil Red Rocket, ran well, in the high-nine-second range, and Harris' skills behind the wheel impressed

"Leonard did such a good job of driving the Fiat that we decided to go with Leonard for our dragster," recalled

As a student of the

"At school, Leonard wasn't really known as a drag racer or a car guy," he recalled. "He was an all-city gymnast, and everyone in the school knew who he was because of that. My first recollection of him driving was at

The skill, strength, and concentration it took to reach that elite level of gymnastics obviously paid off behind the wheel.

"He had tremendous concentration and a lot of muscle coordination," recalled

|

|

|

The 28-year-old Harris made his unofficial debut in the team's dragster – now sponsored by Albertson Olds, which gave the teams parts, including heads, blocks, and cranks -- at Lions April 23, 1960, with a few test passes (the team arrived too late to qualify for the day's racing), and the next day at San Fernando Raceway, the Albertson Olds broke Tommy Ivo's track record with a 9.30, set top speed of the meet at 163.33 mph, and won the event, then did the same thing a week later at Lions.

Two weeks later, after anoither Lions win, Harris set the national record on May 15 at the NHRA Record Meet at Inyokern in

Recalled Adams, "At that point in time, Long Beach was pretty slick when the dew would come in, and if you had a lot of power, you really had to ease into it before you could get after it, kind of like needing a clutch-management system, except the driver had to do it. Later when they learned how to keep it real clean, it ended up as one of the best tracks in the world, but from '59 to about '62 or '63, it was pretty slick. We had a pretty light car for the time and a big-cubic-inch Olds; I had been running Oldsmobile for years, so I knew my way around them pretty good, and Engle was a tremendous amount of help."

Former Top Fuel driver Carl Olson, who counts Harris among his first hot rodding heroes, said, “I've watched a lot of drivers pass down the quarter-mile in my life, but none that ever impressed me more than Leonard Harris. Even before the advent of such technology as reaction timers or, for that matter, even the Christmas Tree starting system, Harris was always the first to leave. I never saw him make a mistake on a run."

Tom Jobe, who in a few years would become part of the successful triumvirate that formed the popular Surfers Top Fuel team, recalled, "I was younger than the Leonard Harris/Gene Adams group, so I was hanging on the fence at

"You could see the way he walked and carried himself that he was a great athlete," recalled Ron Miller, race coordinator for the nostalgia-themed Standard 1320 group. "He was one of those universally well-liked and respected drivers who could drive anything."

|

|

|

Harris' cousin, Lou Senter, who founded Ansen Automotive in 1948 in

"His coordination was so perfect, you couldn’t ask for more," opined Senter. "He would have made a good oval-track driver. He probably was one of the best drivers out there. He had a very good name; everyone told me he was the best there was. He used to come down to Ansen and tell me that he would never watch the flagman; he would watch the lights only. He was always first off the line. He was a very sharp mechanic, too, a very athletic guy, and well-liked. I don’t think there was a mean streak in him. He had a personality that you had to like."

Remembered Greg Sharp, drag racing historian and the Wally Parks

In addition to its Lions skein — during which the team also ran its first eight, an 8.98 July 9 — the team scored Top Eliminator wins at

"Everyone wanted us to go back there," said

Although the fields at Lions were incredibly tough, all of the sport's top names from across the country were in

"

The Albertson Olds team won the A/Dragster class, topping 35 other entries with a 9.65 best, and later ran 9.49 and was selected to run for Top Eliminator against Dode Martin and his and Jim Nelson's twin-Chevy-powered Two-Thing AA/D, which had run 9.49, and James "Red" Dyer, whose '56 Chrysler-powered '27-T Tennessee Bo-Weevil A/Modified Roadster had run 9.89.

|

|

Harris beat Martin in a close battle, then took on Dyer for national bragging rights and a new '60 Ford station wagon that was part of the winner's bounty and finished it off with a sterling 9.25, which also was low e.t. of the meet.

"We figured we had as good a chance as anyone, but there were a lot of twin-engine cars that were hard to beat," said

Before heading home, the team -- which also included Harris' good friends, Davis and Vern Tomlinson -- headed to Minnesota Dragways for a match race with the Bruce "Stormin'" Norman-driven Big Wheel dragster, caravanning with fellow Olds racer Don Ratican and the Ratican-Jackson-Stearns team, towing the Ford station wagon at the Nationals with the eight trophies won between the two cars laid out in the back of the wagon.

Ratican remembers the odd sight he encountered exiting his motel room one day. There was Harris, hanging onto the roof overhang, legs sticking out horizontal to the ground in a show of his former gymnastic skills.

"Leonard was a tremendous driver," recalled Ratican. "He jumped in my Fiat one time and drove it as quick and fast as Ronnie [Stearns] ever did. He could drive anything."

|

|

Harris and Adams again took advantage of t

The match race, however, never happened and set into motion the tragic chain of events that would lead to Harris' death.

"By the time we got there, the Howard's car was already on the trailer," recalled

"We went up in the stands and started watching, and Leonard got an offer to help these guys out who were having a handling problem. He made a pass and then came over and told us it was pulling to the left in the lights but decided to give it another try."

There seems to be some confusion about the name of the entry as time has blurred many memories, but the car into which Harris hopped was either the Firestone Realty or Firestone Auto Wrecking entry, and its regular driver may have been former Adams-Scrima shoe Smith, and a solid handler named Norm Taylor may have also tried unsuccessfully to tame the beast earlier in the day. Again, memories are fuzzy.

Dan "Buzz" Broussard, a longtime pal of

"There was a muffler shop down the street from Keith Black's shop in

|

Broussard, whose own car was runner-up at the 1963 March Meet with McEwen at the wheel, remembers Harris as "a terrific guy, calm, not hyper, mild-mannered; he could adapt to anything." That may have been Harris' undoing; he lost his life on the next pass in the car, in the first round of eliminations.

Some say that the front axle broke, others that a steering arm came off; though the cause of the crash will never be known, it was clear that somehow the car got away from Harris, and as a stunned Lions crowd watched in disbelief, it made a left turn into the catch fence alongside the track and got upside down. Harris succumbed to injuries suffered in the accident.

"Everything was all crunched up, and you couldn't tell what happened," recalled

"I guess I could say, in all honesty, that the only mistake I ever saw Leonard Harris make at a dragstrip was getting into that car that night to do a fellow racer a favor," said a reflective Olson. “I'll never forget that fateful night. I was at the finish line sitting on top of a small concession stand located there, which was not in use at the time. On this run, Harris was matched up against the Quincy Automotive twin Chevy, which was well ahead at the finish line. As a result, I was concentrating on the

The stunning accident cut the heart and a bit of the spirit right out of the team.

"It shook up Scrima so bad he didn’t want to race anymore," said

|

|

Adams and McEwen continued with the now-Albertson-less Olds car for about four months before trading it in for their high-back car and later the Kent Fuller-built Shark car.

"We did real well, but nothing like we did with Leonard," recalled

"The '60s were an amazing time," he added wistfully. "Every week at

Adams, of course, went on to have a successful run with a number of drivers, including Don Enriquez, Jimmy Scott, John Mulligan, Steve Carbone (briefly, after Mulligan broke his jaw in an auto accident), Mike Snively, Billy Scott, Ed Vickroy, and Chess Bushey, and, today, Kin Bates' A/Fuel car in NHRA's Hot Rod Heritage Racing Series.

Still, it's Harris and that amazing summer and early fall of 1960 for which many people most remember Adams, for his amazing yet short partnership with one of drag racing history's best drivers whose life and career were cut tragically short. In 30 races together, they won 22 times at six dragstrips.

Recalled McEwen, "That Albertson Olds car was a stout piece -- one of the only single-engined cars that could beat the duals -- and Leonard was like a computer when he drove it. I remember that Gene would get mad at me because I couldn’t drive it as good as Leonard. He was unbelievably talented. He would have been one of the all-time greats, no doubt about it."