Top Fuel blowovers, Part 2

At first blush, the twin blowovers in June 1986 and August 1987 by Don Garlits’ similarly enclosed front-end Swamp Rat XXX and 31 dragsters may have seemed to be a plague upon his streamliner design, but within a few years, it became clear that although its design no doubt contributed somewhat to the spectacular backflips, the conventional car was not immune to the rotational forces of a rapidly accelerating, fully engaged, fuel missile just itching for takeoff under the perfect storm.

Reader Dan Bogurske, of Orlando, Fla., was the first to ask about a chronology of the phenomenon and even gave me his quick from-memory list that, while impressive, missed at least a half-dozen, but here’s the shout-out to him for the idea, which dovetailed nicely with the recently completed streamliner history.

I’ve been able to compile a list of 18 modern-day (1986-present) blowovers, including the mini epidemic of six from late 1988 through early 1991, so here goes.

|

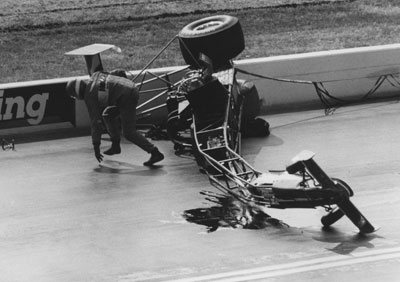

The first to follow Garlits head over heels was Richard Holcomb, at the post-1988-season Snowbird Nationals in Florida. During Saturday qualifying, Holcomb, at the wheel of his new and still-unpainted Woody Mays-built car, flipped ’er overbackward. Although the car initially landed right-side up on the nose, it tumbled down the track after complete touchdown. Holcomb, whose car was tuned by fuel-racing veteran Clayton Harris, suffered only slight burns on his legs and a dislocated left index finger, but the car was pretty much a write-off. I’ve never seen any footage of it, and Insider pal Wade Nunnelly is the only one (to my knowledge) who captured it on still film in the photo at right, part of a six-frame sequence he shot.

Realizing that the blowovers seemed to happen before a driver could react to stop them, Harris designed an adjustable air sensor that could detect an air-pressure change beneath the body panels, indicating that the car was in a wheelstand. When triggered, the sensor activated an air cylinder under the throttle pedal to push it to full-off faster than a driver could lift, and he had plans to add a second sensor that would automatically apply the rear brakes. I’m not sure that was ever implemented, and both are no longer with us to ask, but it was interesting to see the outside-the-box thinking by the former Top Fuel driving great.

The Holcomb sensor debuted at the 1989 Supernationals in Houston in March, just a few weeks after Eddie Hill joined the Unfortunate Flyer Club at that year’s Winternationals. During Friday qualifying, Hill’s first-in-the-fours Super Shops dragster took flight at high speed at the finish line after a front-wing failure at about 1,000 feet. The car was vertical at the finish line – tripping the timers on a 5.210, 236.15 pass -- then sailed several hundred feet through the shutdown area before touching down on the side of its right-rear wheel – which cushioned the blow – then landed upright. The fact that Hill had gotten the chutes deployed didn’t hurt either.

The Holcomb sensor debuted at the 1989 Supernationals in Houston in March, just a few weeks after Eddie Hill joined the Unfortunate Flyer Club at that year’s Winternationals. During Friday qualifying, Hill’s first-in-the-fours Super Shops dragster took flight at high speed at the finish line after a front-wing failure at about 1,000 feet. The car was vertical at the finish line – tripping the timers on a 5.210, 236.15 pass -- then sailed several hundred feet through the shutdown area before touching down on the side of its right-rear wheel – which cushioned the blow – then landed upright. The fact that Hill had gotten the chutes deployed didn’t hurt either.

"It happened so suddenly, it was out of my hands,” said Hill, a veteran of seven previous crashes in fuel boats and dragsters. “Once I started crashing, I covered up my pretty parts [face] with my hands and closed my eyes.”

Another of the sport’s greats, Don Prudhomme, was next to feel the sting of the blowover. Preparing for his return to Top Fuel in the 1990 season, “the Snake” was testing his Skoal Bandit dragster in Bakersfield Dec. 17, 1989. After two days of test launches, “Snake” made a full pass, and, as with Hill’s crash, a front-wing support gave way at three-quarter-track.

Another of the sport’s greats, Don Prudhomme, was next to feel the sting of the blowover. Preparing for his return to Top Fuel in the 1990 season, “the Snake” was testing his Skoal Bandit dragster in Bakersfield Dec. 17, 1989. After two days of test launches, “Snake” made a full pass, and, as with Hill’s crash, a front-wing support gave way at three-quarter-track.

"Everything was fine," Prudhomme recalled, "but when that flap drops, it's like you're in an airplane – you're already going fast enough to take off. It's like throwing a paper cup out of a car going 100 mph. I tried to grab the parachute, but it happened too fast. There was no warning; it just went up and over."

Prudhomme's brand-new Dave Uyehara-built dragster suffered surprisingly little damage; save for a bruise on his knee, "the Snake’s" feelings were hurt worse than anything. "I was bouncing around down there thinking what a shame it was, about what had happened to my brand-new car. I'm still upset about it," he said two weeks later. "I'll be thinking about this one for the rest of my life."

Incredibly, Prudhomme didn’t have long to obsess over that crash because just eight months later, during qualifying at Le Grandnational in Quebec, he joined “Big Daddy” in the Frequent Flyer Club. Prudhomme’s car picked up the front tires early, set them down, then yanked them up again, all before half-track. The car quickly flipped and, unlike in the previous blowovers, landed upside down, cushioned, fortunately, by the rear wing. The car slid on its side for a long time, then backed into and over the guardwall in the shutdown area.

“I grabbed the brake and tried to stop it, but it was just too late. It went overcenter. It was over,” he said sadly.

|

Between Prudhomme’s two flights, yet another veteran fuel pilot, Jimmy Nix – who also would rack up more air miles quickly enough -- went up and over at the Supernationals in Houston in March 1990. Nix’s car, like so many, landed on its nose first before flopping onto its side. Like Garlits before him, Nix kept the throttle planted to try to slow his backward motion, but the engine exploded under pressure, causing a fire. “The Smiling Okie” escaped serious injury.

Interestingly, the next two blowovers occurred – like Hill’s – at the Winternationals: Russ Collins in 1991 and Nix in 1992.

Collins, at the wheel of Bill Miller’s Don Long-built car, started getting up at 300 feet and was straight up at 800 feet. It flew through the air, touched down briefly on its nose, then went through three dizzying barrel rolls before it landed on its wheels right on the finish line.

Collins, a former fuel motorcycle racer and no stranger to wild rides, said, “I always thought – watching [Gary] Ormsby and Hill and the rest of them – ‘I’ll stop it,’ but trust me, there is no way to stop this guy. As fast as I think I am, boy, there’s no way. It is instant.”

Nix’s second blowover, at the 1992 season opener, was another high-speed flight with a hard landing. The car smacked down in the shutdown area, then slid all the way to the sand trap at the end of the track; Nix received burns in the fire that engulfed the car as it slid downtrack.

|

(In the midst of all of this Top Fuel craziness, Jay Payne flipped his Top Alcohol Dragster upside down at the Chief Nationals in Dallas in late 1990. As you can see from my amazing photo at right – I love how the car seems to be suspended solely on the rear wing – there weren’t a whole lot of folks in the Texas Motorplex grandstands at the time for a mid-Friday alky session, but I just happened to have my camera up – which I wouldn’t normally do – between bites of a Drag Dog. There’s no footage of this one, but going from memory, it seems that it was more of a powerstand than a blowover. It happened so quickly off the line that I’m not sure how much effect the air had on it..)

Interestingly (to me, anyway), Dallas was the scene of the next Top Fuel blowover, which occurred in round one at the 1992 event. Doug Herbert had the front wheels up high on the launch, and they just never came down. The car landed upside down and backward before half-track and slid on its side almost all the way to the finish line. I emailed Doug for his remembrances, and he obliged in detail.

Ted Kuburich won third prize in National DRAGSTER's 1992 Photo Contest with this wild shot of an upside-down Herbert at Dallas.

|

As I saw through my camera's viewfinder, Doug Herbert set a new world record for race car evacuation after his 1992 Dallas blowover.

|

“That car ran good, and the front end always danced pretty good,” he remembered. “The day before the blowover [crew chief Jim] Brissette and I tried a few things on [Joe] Amato’s car, and he made one of the first 4.7-second runs. So we gave our car a little bit of a tune-up with what we learned on Joe’s car, trying to run a 4.7 in that first round. We were racing Rance McDaniel and did our normal deal, but I think Rance’s crew had some issues that held them up a little, and that burned some extra fuel and weight off the front of our car.

“When I hit the gas, the front end came up like it always did … and then it came up a little bit more! I should have shut it off (you learn these things with experience), but instead, I just grabbed the brake, and the front end seemed like it was not going to come up any more, until I let off the brake! When I let off the brake, it came up and over pretty quick.

“As I was sliding along on my head, I pulled the fuel shutoffs to get the engine shut down; I also put my hand on the seat-belt lever. I was in the lane next to Jimmy Nix at Pomona when he had a blowover and got burned pretty bad, so that was going through my head. When the car stopped, I pulled off the steering wheel and pulled the belt lever to get out as fast as I could because the fuel line had broken, and nitro was dumping all over the ground, so I wanted to get away from the car and possible fire as fast as I could. We turned that nice Al Swindahl car into a swing set. I hate when that happens. I had bad luck in Texas in '92. At the Houston race, we blew a tire in the lights and bent up that car, and then in Dallas, we had the blowover.”

If you’re keeping score at home, of the 10 blowovers to date, four (Hill, Prudhomme No. 1, Collins, Nix No. 2) happened in California and two in Texas (three if you count Payne). On a personal note, I witnessed (and photographed) more than half of them, including the first Garlits flip, the three Pomona blowovers, Nix’s Houston aerobatics, and Herbert’s wild ride in Dallas, and each truly was a breathtaking moment, that horrifying instance when you realize that something has gone terribly wrong and that the driver is now a mere passenger with his fate in the hands of the strict safety rules and chassis builder’s skill.

Also, all but Garlits’ Spokane, Wash., flip were at NHRA tracks, but that would soon change as it became an equal-opportunity occurrence.

The first blowover at an IHRA event came next as Texan Doug Foxworth flipped his dragster during the first round at the 1993 Spring Nationals at Bristol Dragway, levering his appropriately named Havoc entry up past half-track before flipping it and landing hard in the shutdown area. The actual blowover footage is at about the 1:45 mark in the video at right, but you’ll want to watch what precedes it because it might have set the stage for the blowover. On a qualifying pass, it looks as if qualifying mate John Carey loses an engine and then (perhaps) a rear tire and is seen sliding into Foxworth’s lane in the shutdown area and clipping his front end, which makes me wonder if the front wing somehow was compromised and led to the blowover, a la Hill and Prudhomme. I have an email out to Bobby Rex, Foxworth’s longtime crew chief, to confirm this.

For whatever reason, there was a three-year respite of blowovers, but the one that broke the dry spell was a doozy. It occurred in, of all settings, the final round at the 1996 Gatornationals between Scott Kalitta and Blaine Johnson. I was there for this one, too, stationed by the finish line, and it was the last thing you’d think of happening in a final round.

As you can see in the video at right, Kalitta, in the near lane, gets the front tires up early – they flew over the 60-foot clocks – as evidenced by his 1.002-second clocking – and because it’s night, you can see exactly when he lifts because the fire disappears from the headers, yet as early as he lifted, there was just no saving it. It goes straight up, then lazily falls down on all fours and onto its side, turning lazy circles and eventually backing over the finish line. Johnson, who had smoked the tires early and lifted, moved as far over to his wall as he could to stay clear of the car and got the surprising win with a 10.80-second run. Kalitta, disqualified for banging the wall, stopped the timers with a 14.72.

“As the front end came up, I remember thinking, ‘Aw man, here we go,’ ” Kalitta told National DRAGSTER. He said he stayed with it as long as he could, but before he knew it, “I was looking at the sky. It was that fast. I remember thinking ‘Oh [shoot],’ then it pirouetted and slammed down hard. When it came back around, I was thinking to myself, ‘Did it hit the wall?’ because I was hoping I could still skid there ahead of him. I never saw him.”

The victory was Johnson’s second of the year and third in four races dating back to his breakthrough win at the 1995 Finals. The race had seemed Kalitta’s to win, especially after he made the fastest run in history, 314.90 mph, in round two, and Johnson even allowed that they “turned some screws we probably shouldn't have … when we race Scott, sometimes we do things we wouldn’t normally do because we know what they’re capable of.”

Just a few months later, in Brainerd, Shelly Anderson became the first woman to take flight when her Parts America dragster soared skyward at half-track during Friday qualifying. As in so many other blowovers, the torque rotated the car so that it landed right-side up, nose first, then slid on its side for a long way. Anderson admitted to pedaling the throttle to get through tire shake but that the car hooked up hard and took off, a chronic problem with the lockup clutches of the day. She, too, emerged unhurt, save for a sore back.

OK, we're two-thirds through the master list. I'll be back Friday with the final five, as well as some of the email generated by the first two parts. Thanks for reading.