'Capt. Jack' and the amazing rocket go-kart, part 2

|

|

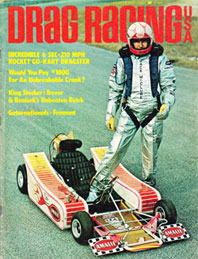

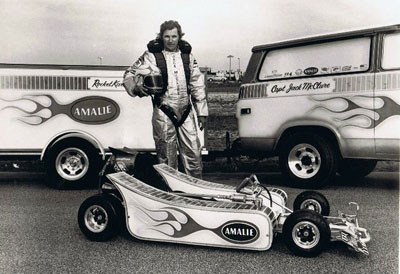

| Jack McClure went from successful fishing-boat captain to the cover of Drag Racing USA thanks to his unique rocket-powered go-kart. | |

Of all the exhibition acts to grace the quarter-mile in the sport’s history, few can match the antics of “Capt. Jack” McClure, whose rocket-powered go-kart made five-second runs at 240 mph, matching the performances of contemporary Top Fuelers with their custom, space-age frames and long wheelbases.

When we left off Part 1 on Friday, our hero, a commercial and charter-fishing-boat captain by day, daring go-kart rider by night, had already established himself as the premier thrust-powered go-kart racer – hell, the ONLY thrust-powered go-kart racer – but those early karts, powered by the sometimes troublesome Turbonique engines, were just the beginning.

McClure’s road to glory had taken some turns, including a five-year stint as a stunt driver for Joie Chitwood, and his attention had turned briefly from the dragstrip back to more conventional karting endeavors. Little did he know that those efforts would soon propel him back to the dragstrip and to unheard-of performances.

While seeking help to manufacture an expansion-chamber muffler for a street-course go-kart race, McClure was introduced to local fabricator Glen Blakely, who knew of his dragstrip exploits and tried to encourage him to return to the quarter-mile. McClure had had enough of the Turbonique engine – the company had pretty much been sued out of business by its customers, according to McClure – but had become interested in the hydrogen-peroxide rocket engine. In a nutshell, hydrogen-peroxide engines made their incredible power very simply: Nearly pure hydrogen peroxide was fed through a nickel-silver catalyst screen that caused the fuel mix to expand approximately 600 times and was expelled through a 2-inch nozzle on the back of the kart, providing thrust much like air being let out of a balloon.

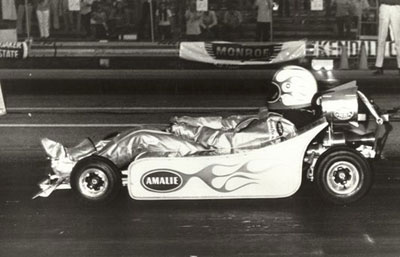

An early outing with the rocket kart

|

“Glen told me if I got the motor, he'd build the kart for me,” remembered McClure. “I thought about it a day and went back and decided to do it. I was standing out on the starting line at Tampa Dragway, and the announcer was telling everyone what I had planned with the rocket engine, and the next thing I know, this guy almost does a flying tackle on me, yelling, 'I got the motor; I got the motor,' and that was Arvil Porter. Arvil built the engine, Glen built the kart, and the rest is history.

“Glen asked me, ‘How do you want to lay in this thing?’ so I got up on the table, got in a position, and he blocked me up with blocks and started bending the chrome moly tubing right there. I was up on that table for 45 minutes to an hour, and when I got down, the pattern of the frame was already tacked together.”

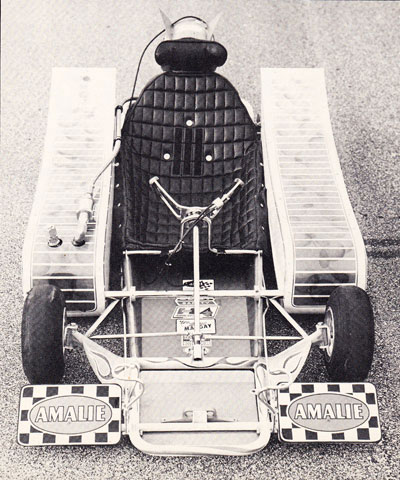

The new kart had a wheelbase of just 52 inches, but it was a full-laydown design, a stark contrast to the near-upright position he’d driven in before. The new position made the kart more aerodynamic and stable, and side fairings that hid the nitrogen and fuel tanks also aided the aero package.

“The amazing thing about that go-kart was that Blakely hit it right on the head,” added a still-in-awe McClure. “It was stable as hell, inch and half off the ground."

Not that he didn’t have his moments.

Steve Reyes photos

|

|

|

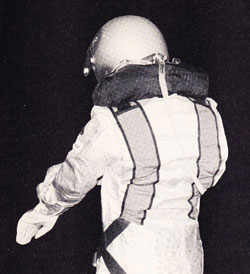

(Above) Three strips of Velcro on the seat kept McClure glued to the kart. (Left) In the event he did exit the kart, a neck-mounted parachute presumably would slow him to safe stop.

|

|

|

|

A more conventional stopping method was used. Twin rear disc brakes also aided deceleration.

|

|

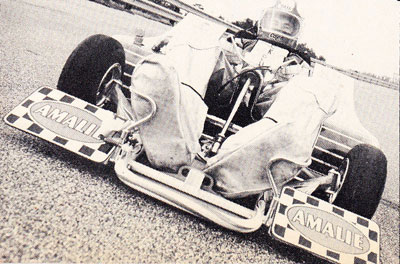

Between-the-legs driver vantage point wasn't for everyone ...

|

|

“The first time we ran it at Sunshine Dragstrip in St. Pete [Fla.], we didn’t have the fairings on, and at 150, we thought it would take off and fly. I ran on some rough tracks; at Tulsa, there was a bump right in the lights, and the Top Fuel cars would bottom out there. They said I was a foot and a half in the air, but it came right back down.”

According to McClure, driving the kart was a pretty straightforward proposition – at least in his mind: “It was easy to drive if you had the nerve to hold it down.”

For a typical quarter-mile pass, McClure would load it up with four gallons of fuel and run it wide open; at about 1,000 feet, it would run out of fuel. Getting going was no problem; stopping was another story.

“Fred Sibley brought us a big ol’ ribbon chute to try -- 10 foot with short shroud lines – and the first time I used it was at Rockingham. I ran 178 mph, and it took the whole back end off. We went to a 5-foot ribbon chute that Jim Deist had made for 200-mph motorcycles at Bonneville.”

The open nature of the kart also had its other perils. “If your head got up an inch too high, it would try to suck your helmet right off,” he said. To help ensure that he himself wasn’t sucked off the kart, he had three Velcro strips on the suit and his seat.

Through John Paxton, who drove the Courage of Australia rocket dragster, McClure also worked with Deist on the driving suit with an attached parachute, a last-ditch safety measure should McClure ever became separated from the kart.

“They told me, ‘We need to test this thing.' They wanted to go on a grassy patch and slide me off the back of a truck at 100 mph and let the chute open so I could get the feel for what was going to happen.’ Lucky for me, it rained three or four days and was too wet to test; that was good news to me. I never did test it.”

With McClure almost flat on his back, he had to look through his legs to drive, making the whole thing a bit unnerving for some.

“We were running out in Tulsa at the [AHRA] Springnationals, and Don Prudhomme asked me if he could sit in it. He's all legs – he looks like a damn grasshopper -- so he sits down in it, and I get him to slide forward in the seat right up against what I called the jewel pad. Every time he'd slide down an inch, his legs would go up 3 inches. I had him lean back in the seat and told him, 'Look through your knees; now you’re ready to go.' He looked up at me and said, 'F--- you.' The racers were more amazed than anyone else that I’d drive that thing.”

Listening to McClure spin his tales, it sometimes seemed as if his greatest concern was the track operator.

“With my old kart, it got to where if I went 122 here, they wanted me to go 125,” he said. “Later, some of them got to boosting the time up. I told them, ‘If I run 190, that's what you announce; if I run 220, that's what you announce. Don't add nothing to it. They always wanted more and more.

|

“One time in New Hampshire, I almost hit this light pole,” he remembered. “It was eighth-mile, and they told me, ‘Last week, Don Garlits was here and ran 186 to 187 mph; you gotta beat that.’ I said, ‘This place doesn't have any shutdown area. They said, ‘Well, we have a sand trap.’ I said, ‘I'm not running this thing off into a sand trap.’ I went down and looked at it, got out the Sibley chute, which I still had, and said I’d do my best. I made the run and stood on it all the way. I held it all the way through the lights, and the chute picked the back end up. I only had brakes on the rear axle, which was a live axle, and just out of habit, I had my foot on the brake. When it came down, it slid sideways right by one of the poles. I went back and measured and missed it by about 10 inches. I wasn’t scared.

“I also ran 189 mph on the run,” he added proudly.

"Another time, in Muncie, Ind., it rained, and the race was called. I was talking to media, and [IHRA President] Larry Carrier says, ‘ "Capt. Jack," suit up. There's a lot of people out there; we have to give them a show.’ The track’s wet, and there are puddles everywhere. ‘We'll run some cars down there and splatter it around for you,’ he said. I ran down there, looked like a hydroplane running, and still ran 190-something.

“Anther time, I was running a brand-new smooth track. I could throttle the engine – it had a ball valve throttle – so I backed out just a little to have something at the end and still ran 215, but Carrier chewed me out for doing it because he wanted to go all year long building me up to 200. He said, 'Now you have to go 200 mph every time you run.'

|

“I ran once at Charlotte Motor Speedway using pit road. They asked me, ‘How you going to stop?’ I just said I’d go around the track, which I did three or four times. A motorsports writer for the Charlotte Observer told me I was so popular there I could run for mayor and win. I ran for IHRA and AHRA – NHRA never did approve it – but IHRA and AHRA were so happy they told me, ‘We hope NHRA don’t ever approve you.’ "

It didn’t take long for McClure to become a popular draw from coast to coast, and he was happy to take every booking; his per-run profit margin had him living high on the hog.

“I’d run two shows a week at $250 per run, but it only cost me $40 per run. Some guys would pay me $1,000 to run a show. We were checking into Holiday Inn with two king-size beds for $8 a day; Motel 6 was only $6 a day. Gasoline was 29 cents a gallon. Between my go-kart and fishing, I had a house down on the water on the Isles of Capri, beachfront Florida property."

McClure originally started with a 1,000-pound thrust motor but later upped it to 1,500, which pushed him from low-six-second passes into the fives. He recalled his first five-second pass coming at the Manufacturers Meet at Orange County Int’l Raceway in 1973.

“[Noted rocket-car racer] Ky Michaelson showed up and asked, ‘What kind of pressure you running?’ I said 350. He said, ‘Let’s crank this thing up.' He went up 50 pounds, and it ran in the fives. I think the best I ever ran was 5.90 at Union Grove [Wis., Great Lakes Dragaway].

“Everywhere I went, it was just unreal, but I didn’t think a whole lot about it at the time. Now, 35 years later, people are still amazed. I came up from 40-mph go-karts; I wasn't any stranger to running fast in a go-kart. It was something else, but even I didn’t realize what I was doing was as big as it is.”

Rocket-car racers Ramon Alvarez and Russell Mendez bought the kart from McClure and rebranded it Free Country but didn't run it much.

|

McClure made his last run in the car in November 1973 and sold the car to Russell Mendez and Ramon Alvarez.

“I had come to Florida to get into fishing and had done everything I could with the kart, set all of the records, and there wasn’t anything else to do. My wife at the time said, 'Every time you drive that car, you’re putting another nail in your coffin,' so I quit.

“[Mendez and Alvarez] wanted to buy it and offered me cash money, so I sold them the kart with the guarantee that I would get first option to get it back. They changed the color, the paint scheme – it had mountains and stuff on it; they were into this hippie stuff -- and called it Free Country. Ramon drove it, but he was big, and it was built for me. He was shorter in the legs than me and was uncomfortable. He told me it scared the hell out of him.”

The plans of the ambitious Mendez and Alvarez, who also at one time bought Don Garlits’ Jocko Johnson-built Wynn's-Liner with the intent to turn it into a rocket car, were derailed by Mendez’s death at the 1975 Gatornationals in the Blakely-built Free Spirit rocket dragster.

“I heard Ramon died a few years ago. Glen Blakely also has died, and Arvil died, too. I'm the lone survivor. I'm an old man, 85. I'm a young 85. I’ve been blessed with good health and a long life, still have my tonsils, my appendix, and my hair." [Update 2/9.2012: Contrary to McClure's belief, Glen Blakely has not passed away.]

(Above) Among his occupations since he left racing, McClure, center, was part of a Western-themed stunt show that played at fairs across the country. (Below left) McClure and friends at the Bacardi international boat show in Miami in 2010, where one of his boats was chosen for a photo shoot.

|

|

|

|

And the location of the famed kart?

“I heard Ramon got into some legal trouble before he died, and it's stashed somewhere after the government took it away from him,” he said. “I had a friend in law enforcement look for it, but there's no record of it being confiscated. I also heard that [late jet-car driver] Lynn Redeman bought it. Steve Reyes told me that Ramon sold the kart to Lynn Redeman and had it tied to the back of his trailer, and it came loose, fell on the highway, and caused a six-car pileup, demolished the kart. I don't think that happened. If that had happened, someone would have known for sure. To be honest, I don’t know what ever became of it.”

There’s no doubt that McClure’s place in the annals of drag racing is well secure, thanks to his bravery and a tenacity of which he remains proud.

“I always had an inferiority complex,” he said. “I looked at people and thought, ‘That guy's above me,’ and when I was racing, I always tried to beat that guy. The design of the kart, the performance, it all just came together. I guess I had a little to do with it.”

And even though Drag Racing USA’s cover story on McClure asked the question “Crazy or courageous?” McClure also is most proud of the comments posted online by his peer Michaelson.

“Everyone said this guy was either crazy or he had a death wish,” he wrote. “Jack was neither of them. Jack was an entertainer; he also had the best halftime act in drag racing for a number of years.”

Amen to that.