The Duntov Letter

It’s almost impossible to imagine American performance — or drag racing itself — without Chevrolet. The small and big-block V-8s, factory-backed performance parts, and its deep investment in racing are now woven into the sport’s DNA. But that wasn’t always the case.

In the early 1950s, hot rodding belonged almost entirely to Ford. The flathead V-8 powered hot rods, dry lakes racers, and roadsters across America, and the aftermarket — and the culture — revolved around the Blue Oval. But Chevrolet began to close that divide in December 1953, when a recently hired engineer put his hot-rod thoughts on paper and, in doing so, helped redirect the future of the American performance industry.

A Letter That Marked a Turning Point

The letter was addressed to Maurice Olley, director of research and development for the Chevrolet Motor Division. Its author was Zora Arkus-Duntov, a Belgian-born Russian, German-educated, and deeply fluent in the language of racers. Duntov was not the first Detroit insider to understand hot rodders. Others before him had recognized the movement’s momentum and cultural gravity. But few had Duntov’s combination of engineering credibility, racing experience, and access to the factory levers that could actually create change. By the time he wrote the memo now known simply as "The Duntov Letter," he had already earned respect outside the corporation.

Before joining GM, Duntov co-developed the Ardun overhead-valve conversion for the Ford flathead V-8, one of the most significant performance innovations of the era. He understood how hot rodders thought, how they spent money, and why they were cautious about new platforms. More importantly, he understood that performance credibility wasn’t created through advertising — it was earned through parts, reliability, and competition.

Understanding the hot rodder In his three-page memo dated Dec. 16, 1953, Duntov laid out a clear-eyed assessment of the performance landscape. Hot rodding was growing rapidly. Publications devoted to speed and hop-up culture had exploded in circulation. And nearly all of that attention was focused on Ford. Hot rodders, Duntov noted, didn’t just favor Ford, they knew Ford. They had years invested in development, parts compatibility, and hard-earned experience. That loyalty wasn’t emotional (yet); it was practical.

Chevrolet, meanwhile, faced several disadvantages: late entry into the overhead-valve V-8 market, an aftermarket almost entirely geared toward Ford, and a racer population already deeply entrenched in existing platforms. Duntov’s insight wasn’t simply that Chevrolet needed to catch up, but that it needed to remove friction. Hot rodders were conservative not because they lacked imagination, but because new development was expensive and time-consuming. If Chevrolet wanted their attention, it had to make performance accessible.

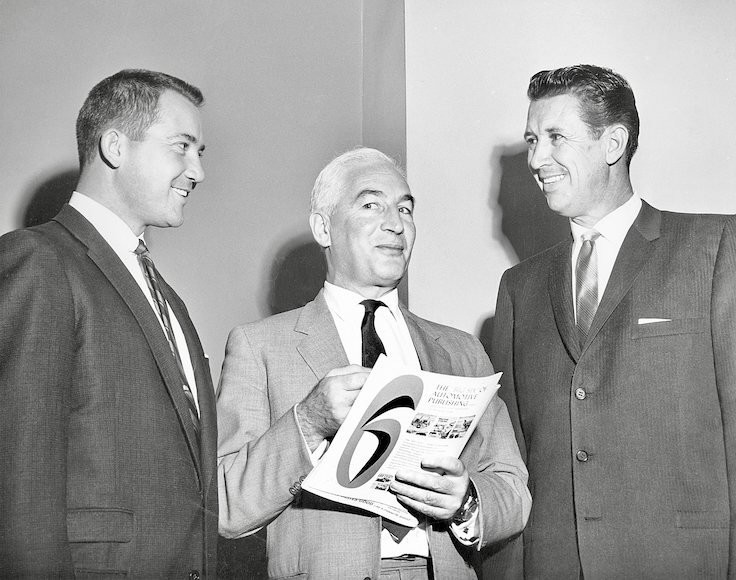

(Seen from left to right: Hot Rod magazine's Robert E. Petersen, Chevrolet's Zora Arkus-Duntov, and NHRA's Wally Parks)

A Strategy Rooted in Racing

The solution Duntov proposed was both bold and pragmatic: Offer engineered performance parts directly from the factory. Camshafts, manifolds, valves, pistons — components that hot rodders needed, trusted, and were willing to pay for — should be developed, validated, and made available. Not as aftermarket experiments, but as factory-backed solutions. Public association with hot rodding, Duntov acknowledged, might be uncomfortable for a conservative corporation. But the Corvette offered a path forward. By positioning performance parts as Corvette options, Chevrolet could engage racers without overtly aligning itself with street hot rodding. And racing, Duntov argued, was inevitable. Whether Chevrolet approved or not, Corvettes were going to be raced. If the factory didn’t help, racers would turn elsewhere — often with mixed results. Supporting competition, even in small numbers, offered publicity far beyond the scale of participation. If racing couldn’t be stopped, it should be done safely and done well.

The Industry Changes Course

The Duntov Letter did not singlehandedly invent factory performance, nor did it instantly convert Chevrolet and Detroit into a racer-first industry. But it marked a clear inflection point. What followed was a gradual but decisive shift: factory-backed performance parts, increasing engagement with drag racing, and a recognition that enthusiasts were not a fringe audience, they were influencers, early adopters, and long-term customers. From Chevrolet’s regular production options (RPO) performance offerings to the rise of the small and big-block V-8s as the engines of choice in drag racing, the blueprint outlined in Duntov’s memo became reality. More broadly, it helped legitimize racing as a proving ground for engineering and hot rodders as partners in innovation. The performance industry changed when Detroit stopped talking at racers and started listening to them.

Legacy

Today, it’s easy to take that relationship for granted. Factory support, contingency programs, performance catalogs, and deep OEM involvement in drag racing are now standard practice. But that relationship had to be earned. Reflecting on the impact years later, NHRA founder Wally Parks captured the significance succinctly: That letter changed the relationship between Detroit and the hot rodder. The Duntov Letter wasn’t just a memo. It was a signal, one that helped align Detroit engineering with grassroots performance culture and ensured that drag racing would become a proving ground not just for racers, but for manufacturers as well.

Read it For Yourself

To: Mr. Maurice Olley

From: Mr. Z. Arkus-Duntov

Subject: Thoughts Pertaining to Youth, Hot Rodders, and Chevrolet

Date: December 16, 1953

The hot rod movement and interest in things connected with hop-up and speed is still growing. As an indication: the publications devoted to hot rodding and hop-upping, of which some half-dozen have a very large circulation and are distributed nationally, did not exist some 6 years ago. From cover to cover, they are full of Fords. This is not surprising then that the majority of hot-rodders are eating, sleeping, and dreaming modified Fords. They know Ford parts from stem to stern better than the Ford people themselves.

A young man buying a magazine for the first time immediately becomes introduced to Ford. It is reasonable to assume that when hot-rodders or hot-rod influenced persons buy transportation, they buy Fords. As they progress in age and income, they graduate from jalopies to second hand Fords, then to new Fords.

Should we consider that it would be desirable to make these youths Chevrolet-minded? I think that we are in a position to carry out a successful attempt. However, there are many factors against us:

1. Loyalty and experience with Ford.

2. Hop-up industry is geared to Ford.

3. Law of numbers thousands are and will be working on Fords for active competition.

4. Appearance of Ford's overhead V-8, now one year ahead of us.

When a superior line of G.M. V-8s appeared, there where remarkably few attempts to develop these and none too successful. Also, the appearance of the V-8 Chrysler was met with reluctance even though the success of Ardun-Fords conditioned them to the acceptance of Firepower.

This year is the first one in which isolated Chrysler developments met with success. The Bonneville records are divided between Ardun-Fords and Chryslers.

In the non acceptance of G.M. V-8's and very slow beginning of Chrysler, cost must have played a part.

Like all people, hot-rodders are attracted by novelty. However, bitter experience taught them that new development is costly and long and therefore are extremely conservative. From my observation, it takes an advanced hot-rodder some three years to stumble toward the successful development of a new design. Overhead Fords will be in this state in 1956-1957.

The slide rule potential of our RPO V-8 engine is extremely high but to let things run their natural course will put us one year behind and then not too many will pick Chevrolet for development.

It seems that unless by some action the odds and the time factor are not overcome, Ford will continue to dominate the thinking of this group. One factor which can largely overcome this handicap would be the availability of ready engineered parts for higher output.

If the use of the Chevrolet engine would be made easy and the very first attempts would be crowned with success, the appeal of the new will take hold and not have the stigma of expensiveness like the Cadillac or Chrysler, a swing to Chevrolet may be anticipated. This means the development of a range of special parts camshafts, valves, springs, manifolds, pistons and such which will be made available to the public.

The association of Chevrolet with hot rods, speeds and such is probably inadmissible. But possibly the existence of the Corvette provides the loop hole. If the special parts are carried as RPO items for the Corvette, they undoubtedly will be recognized by the hot rodders as the very parts they were looking for to hop up the Chevy.

If it is desirable or not to associate the Corvette with the speed, I am not qualified to say, but I do know that the in 1954, sports car enthusiasts will get hold of Corvettes and whether we like it or not, will race it. Most frequent statement from this group is "we will put a Cadillac in it". They are going to, and I think this is not good! Most likely they will meet with Allard trouble that is breaking sooner or later, mostly sooner, everything between the flywheel and road wheels.

In 1955, with V-8 engine, if I needed to they will be still outclassed. The market-wise negligible number of cars purchased for competition attracts public attention and publicity out of proportion to their number. Since we cannot prevent the people from racing Corvettes maybe it is better to help them to do a good job at it.

To make good in this field, the RPO parts must pertain not only to the engine but to the chassis components as well. Engineering-wise,Development of these RPO items, as far as the chassis concerned, does not fall out of line with some of the planned activity of our group.Use of light alloys, and brake development composite drums, disc and such are already on the agenda of the Research and Development group already.

As I stated above, V-8 RPO engine has a high power potential it is hard to beat inches, but having only 80% of cubic inches it has 96% of square inches of Pittston area of the Cadillac. In my estimation, the power output comparable to the Cadillac can be obtained not exceeding 270 ft.lb. of torque at any point. (323 ft.lb. of Cadillac)*. The task of making powertrain reliable is therefore easier.

These thoughts are offered for what they are worth: one man's thinking aloud on the subject.

Z. Arkus-Duntov December 16, 1953

* The comparison pertains to a special type of Cadillac