When Garlits calls ...

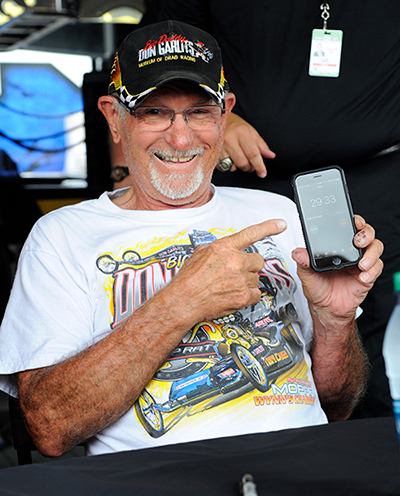

I was lying in bed Wednesday morning, checking email on my phone in preparation for another busy day, when an incoming call took over the screen. It was Don Garlits, and when Don Garlits calls, you answer.

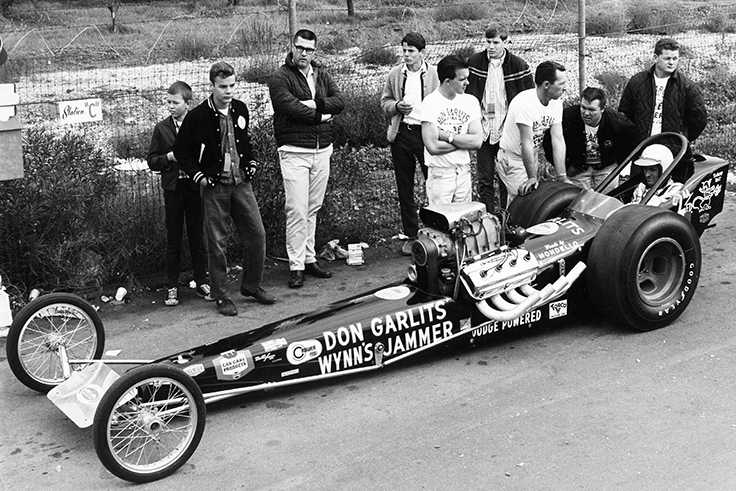

“Big Daddy” is a legend in the drag racing world and even though he long ago hung up his famous black racing helmet, the 92-year-old icon always has plenty to talk about. And for a drag racing history nut like me, another chance to talk to the legend is not something you turn down. Ever.

“Hello, Phil. It’s Don Garlits. Sorry about calling you so early, but I need your help.”

Me? Don Garlits needs my help? The hapless pit rat who somehow turned a teenage obsession with drag racing into a lifelong writing career? The grown man who still gets goosebumps when a famous name lights up his phone?

Well, because I was fairly certain he wasn’t calling to ask me how many grams of weight to put on his clutch or which size capacitor to use in one of his electric motors, I was thrilled to offer my assistance.

“Do you remember when I drove Shirley’s dragster back in 1989?” he asked, as if anyone could ever forget the weekend when two of the sport’s fiercest rivals shared a car and made magic at Texas Motorplex.

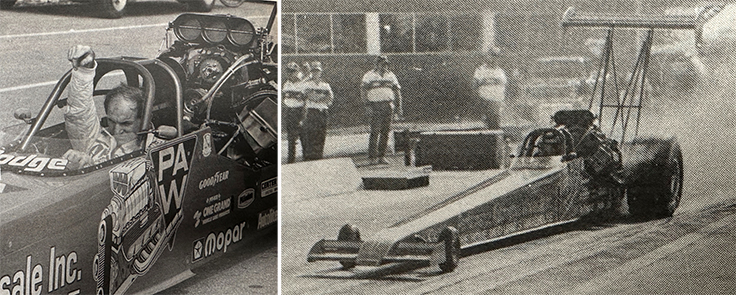

Turns out that Garlits still has Shirley Muldowney's bright-pink Performance Automotive Wholesale dragster that she donated to his museum years ago, and it was about to be loaned to the new Motorsports Hall of Fame of America museum in Daytona Beach, Fla., and he wanted to check on the numbers they both ran that weekend to provide the museum with information for the display.

Allow me to backtrack a bit and set the Wayback Machine to 35 years ago to give you a little backstory.

It was 1989, a year or so after Garlits had retired from driving (again) following his spectacular blowover wheelstand in Spokane, Wash., in the summer of 1987. "Big" was doing color commentary with Steve Evans and Dave McClelland for Diamond P Sports’ NHRA television coverage.

Muldowney, on the other hand, was entering her fourth year of competition after coming back from her near-career-ending crash in Montreal in June 1984 and was struggling. She had reached just three semifinals in the previous three seasons and was having a particularly hard time against a quartet of racers — Darrell Gwynn, Joe Amato, Gary Ormsby, and Eddie Hill — who had zoomed into the spotlight and the winner’s circle during her absence, and although she logged several top-half qualifying spots, she had DNQ’d twice in 1988, including at, of all places, the U.S. Nationals.

So, she did the unthinkable, and asked Garlits, her one-time arch nemesis, to be a consultant for the team in 1989. It’s something that anyone who watched them go at it hammer and tong since the mid-1970s would never have expected, akin to Magic Johnson asking Larry Bird to help him with his jump shot.

But age and circumstances had melted the ice between the two Top Fuel icons.

“We were blood enemies at one point,” Garlits admitted, “but after she had the wreck in Montreal, I never said another harsh word to her. I felt so bad about it because I thought she was probably gonna die. It was such a terrible wreck. All of a sudden I realized that all those races didn't mean nothing. A friendship was what was important.”

Garlits joined the team in Atlanta, and I’m not going to say that Garlits’ addition to the team was the sole reason that 1989 was a major improvement — that would be an insult to her and her team — and they did DNQ three times early in the season before catching fire around the time of the Western Swing. Muldowney set top speed of the meet at 287.72 mph in Seattle and then, at the next event, reached the final round in Brainerd – her first final since winning the 1983 World Finals – and even though she lost there to Amato after smoking the tires, clearly the car was becoming a killer. Muldowney had left on everyone that day except for Amato and clearly was the driver to match the car.

Muldowney had run a string of 5.0s but not yet her first four-second pass that would gain her entry into the Cragar 4-Second Club launched more than a year earlier. Spots were filling up, and she wanted one.

Inexplicably, the team faltered at Indy and failed to qualify, finishing 20th though only three-hundredths shy of making the field.

Redemption came two weeks later in Reading where Muldowney booted her dragster to a 4.974 to secure her coveted spot in the club and earned her first No. 1 qualifying position since the 1982 Montreal event. More importantly for Garlits, it opened the window for him to try to also gain access to the club.

“When I went to work for her, she promised me a ride if I got her in the fours and I'd forgotten all about it,” he told me. “When she made that four-second run in Reading, she said, 'Where do you want to take your ride?' And I said, 'What?' and she says, 'Don't you remember you wanted to take a ride in the car?' I said 'I'll take that ride in Dallas.' "

By the time Garlits stepped into the trademark pink dragster during Thursday qualifying for the Chief Auto Parts Nationals Oct. 5 at Texas Motorplex, the car had also qualified No. 1 again in Topeka, so hopes were high that "Big" could, well, go big and add a 4-Second Club card to his original 5-Second Club membership. Because the event at that time featured five qualifying sessions, the team had at least one to give up to Garlits.

As Garlits saddled up for his first run – back then, a new driver/car combo got a free half-track checkout pass before qualifying -- he knew exactly how long it had been since he’d planted the loud pedal in Spokane: "Two years, one month, 14 days,” he told us. (You can read the text of my original National Dragster story here.)

Shirley urged Garlits to drive the car like it was his own but, much to everyone’s dismay, Garlits smoked the tires at the hit. The car was detuned for the first official qualifying shot which, serendipitously, afforded Garlits a solo pass, so all eyes were on him. That he would run better than his previous career bests of 5.26 and 275.65 mph seemed almost a given – but could he run in the fours?

Twas not to be, though he came close, clocking a 5.072 at 287.71 mph — as fast as the car had ever gone. The 4-Second Club would fill up in February 1991 — Don Prudhomme and Kenny Bernstein were its final two members — and it would be 12 more years before Garlits got his first four-second pass, behind the wheel of Gary Clapshaw’s dragster at the 2001 U.S. Nationals.

After Garlits’ pass in Dallas, Shirley took back the cockpit and made the then-fastest run of her career, 289.66 mph, in qualifying. A week after the Dallas event, the PAW dragster carried Muldowney to her 18th and final Top Fuel win at the Fallnationals in Phoenix, enjoying a satisfying Sunday that featured a first-round win over her other nemesis, Connie Kalitta, and revenge on Amato and Gwynn in the final two rounds. [Read the original race report here]

Ironically, much as Garlits had to wait years for his first four, Muldowney had to wait 11 years to exceed 290 mph, which actually happened on her first 300-mph pass at the 2000 U.S. Nationals. Muldowney had sat out most of the 1990s, hence the big gap, but they both finally got there.

After I’d given Garlits the stats he was looking for on the 1989 car, I wasn’t about to let him go, and he clearly didn’t have a lunch date either, so we talked for another half hour on a variety of topics that I absorbed like the speed-smitten sponge I am.

As I mentioned earlier, Garlits is 92 now, but his mind remains a steel trap on dates and facts. Every time we talk, he’s not guessing or generalizing about anything. We’re so blessed that not only is he still around and sharing stories of his amazing career, but that he’s still really here in every way.

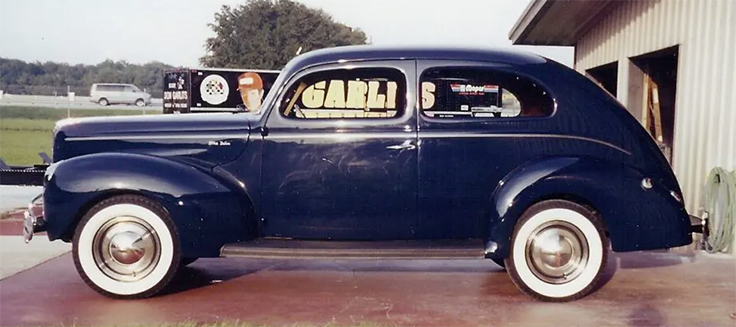

"My first drag race was in September 1949," he told me, and I bet he'd have told me the exact date if I had pressed him. "I had just bought my first car, a '40 Ford that I had bought for 350 bucks. I was on the way home on Florida Avenue and I stopped at the Buffalo Avenue light. This kid pulled up beside me; he was my buddy and was in the 12th grade, too. His dad was a rich construction contractor and he just bought him a new '49 Chevy coupe. We had the windows rolled down because no one had air conditioning back then, and he hollered over at me, 'When the light turns green, let's race.' I didn't know what he meant; I had never done that before. But when the light turned green we stepped on it. That Chevy shot way out in front of the little Ford because it was worn out, but it was so thrilling. We probably only went out 50 feet but it was such a thrill. I knew that's what I loved. I can remember it like yesterday."

A restoration of that Ford is in his Florida museum, which opened in Ocala, Fla., in 1984, and, as we talked about the place, it took us down a few interesting paths.

“We found this property by praying for it,” he said. “We’d never had any visitors in Tampa for six years and we sold 11,000 tickets [in Ocala] the first year. I tell people this is sacred ground. God has played a big role in my life, and I don't mind telling anybody about it. I tell people 'I don't believe in God, I know about him; there's a difference.’ “

Garlits reverent religious beliefs — best embodied by the “God is love” message in a white cross that rode on his cowl — actually cost him some sponsorship money years ago.

“I've had a cross on my cars since 1978, and that was the year I lost the Navy sponsorship. I had been a volunteer Navy recruiter since 1976 and in 1978 they wanted to give me money, and I needed it. The Navy was giving [Funny Car racer Tom] McEwen money and they had a few extra bucks they wanted to give me. I painted the car blue and white and put the cross on it, but when they came to Pomona with a check, they saw the cross and said, 'We can't do this because that would offend atheists' they thought would want to join the Navy. I said, 'My God, you’ve got a chapel on every ship,' and they said, 'We don't make them go in there. If you don't take that cross off, we're not gonna give you the money.’ I said, 'Look, I didn't ask for the money in the first place. I'm a volunteer naval recruiter,' so that deal ended, but I remained a volunteer naval recruiter for 30 years and that car won $600,000 over a two-year period, so it wasn't all bad. It's one of my favorite cars.”

I reminded him that, religious beliefs or not, his museum was sacred ground to all drag racing fans, and how thrilled we are that he’s still so active.

“I’m sitting here in 65,000 square feet of buildings, housing all the history of drag racing and almost every one of my own cars,” he said. “Only God could allow that to happen. No one man could have done all this. And I still love to come to the museum and meet the fans, every chance I get.”

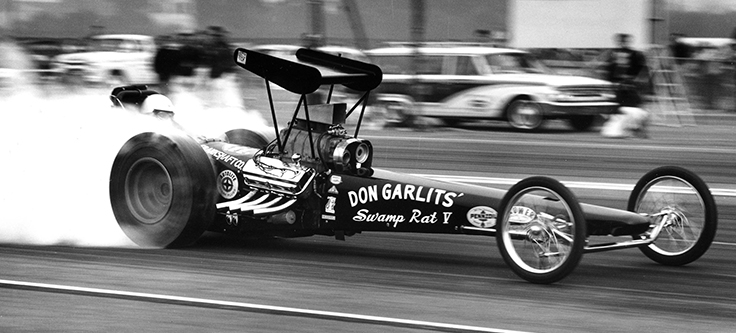

I seized on his “almost every one of my own cars” nugget and asked which ones were missing, and there are only two, one of them being the famed winged Swamp Rat V that won Top Fuel at the 1963 Winternationals.

“We put a wedge motor in it for Chrysler and loaned it to them and it went on a tour of the Dodge dealerships,” he recalled. “In the meantime, my boss at Chrysler retired, so when it came time for the car to come back, they didn’t know where it went, and I've never been able to find it.

“I know it's out there somewhere because nobody would have torn it up or destroyed it. It's in someone’s garage somewhere. I've put ads in the papers, and I've sent detectives all around the country running down leads; never found it. There is another slight possibility: At Chrysler, there was a time when they borrowed all that money and the government made them destroy a lot of stuff — molds for the big block motors and a lot of their race cars and stuff that they had — and it's possible that the car got destroyed in that clean up.

“It’s incredible. I’ve brought my cars back from Holland, from Australia, from Canada, and from all over the United States. Swamp Rat VII-A, which was built for [Connie] Swingle with the swoopy tail section and the car that he won the Drag News race with, he crashed that car at U.S. 30. It wasn't a bad crash. He just kind of ran over the edge of the strip and dumped it over and it bent the frame a little bit. He pulled all the good parts off of it and left the frame by a dumpster and came home. I really chewed him out. Years later, in the 1990s, I was at one of Roger Gustin’s Super Chevy shows in Indianapolis and this fan walks up to me and he says, ‘How would you like to have one of your old car frames back?’ He didn’t know which one it was but said he found it by a dumpster at U.S. 30 and took it home. Oh my god, it brought tears to my eyes. That was an easy one.

“I sold Swamp Rat VI-A to Spencer Krumholtz [in 1964] and I found it at a swap meet in New Jersey, but I was never able to find VII-B. We sold it to Richie Bandell but he retired down in Florida and doesn't remember what he did with it, but that was really one of the minor ones compared to the winged car, which we made a re-creation of because it was so important.”

(Don't know your Swamp Rats? Check out my Swamp Rat Spotters Guides: SR-1 to SR-10 | SR-XI to SR 20 | SR-21 to SR-34)

As our time wound down, I again expressed my admiration for him and how good it was to still be able to talk to him when so many of our other heroes have left us. Behind me on the wall, as it has been for years, was Jeff Caudle's intimate portrait of Garlits in the cockpit. I feel him looking over my shoulder all the time, and he's there watching everyone on my many weekly video calls.

“Phil …” he said in a tone that I knew was about to be followed by some wisdom, and I leaned in to absorb it. “If you want to live to be old age, don't stop working, but that’s only if you love what you do. If you're doing something you don't love, you won't live long. I'll never forget my stepfather telling me I shouldn't be a bookkeeper because I didn't like it. I should work on cars and I'd be successful. You never realize that living a long time has everything to do with doing something that you love.”

Damn. I guess I’m going to live into my 90s, too, then. Thanks, ‘Big.” We love you.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator