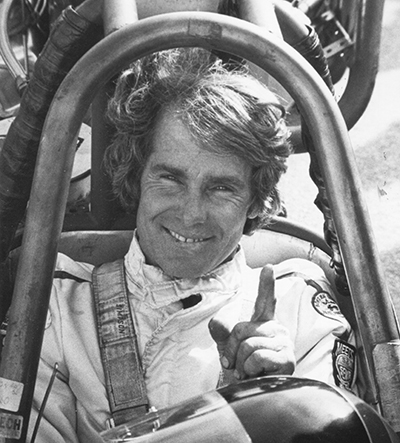

Remembering Bill Mullins

Over the course of 40-plus years on the job, you meet a lot of racers. The overwhelming majority of them are nice, friendly, and open and accommodating of our probing and sometimes difficult questions. And then there was Bill Mullins, Southern Gentleman Personified.

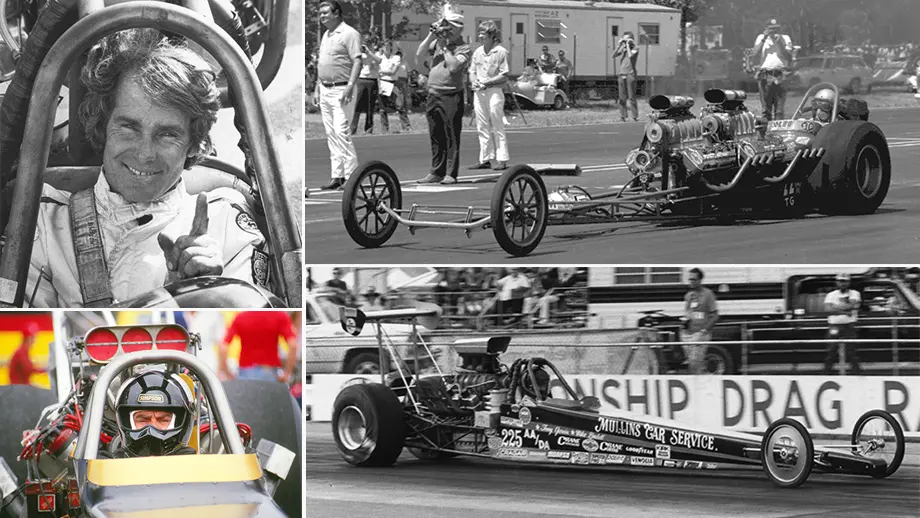

Mullins, of Pelham, Ala., was already in his 50s and well-established in the sport when I first met him in the mid-1980s in what was the final act of a career as a versatile dragster pilot. He was driving one of a trio of Top Fuel cars owned by Delaware diesel mechanic John Carey — Carey and Hank Endres drove the other two — and his legend as a former Top Gas and Top Alcohol Dragster driver was well known to all.

He'd end up a national event winner in all three dragster classes — three different kinds of fuel gas, methanol, and nitro — the only driver in NHRA history to pull off that hat trick. We lost Bill Mullins April 10 at age 88, but his memory lives on with his family, friends, and fellow former racers.

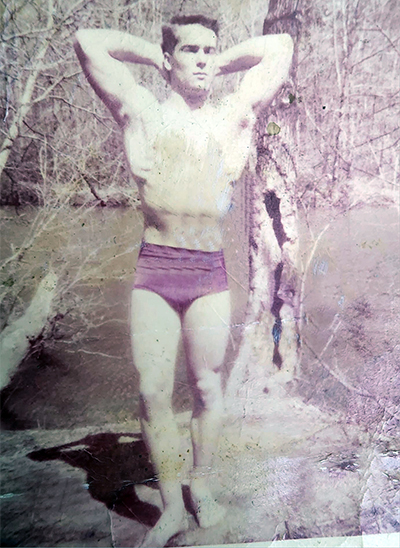

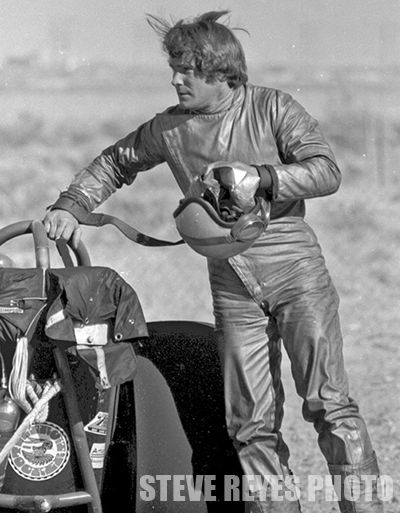

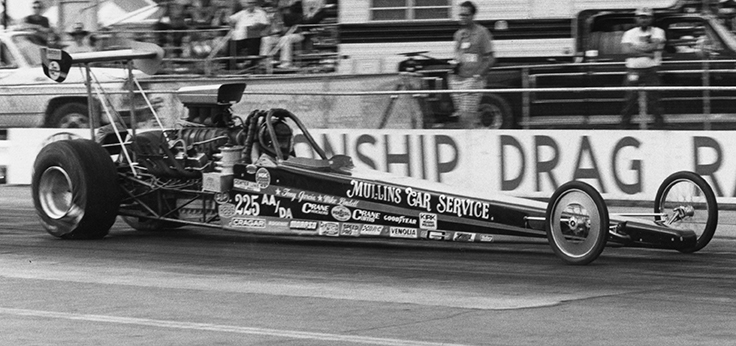

Mullins, a star offensive guard on the football team at Shades Valley High School in the Birmingham area, also had a fondness for weightlifting — which would carry him to a Mr. Alabama bodybuilding title in 1957 over 42 other contestants and to a 292-pound overhead press record that still stands — but he excelled in auto mechanics. He opened Mullins Car Service in 1956 and worked there for more than a half-century, but before that, his first project was his mom’s flathead-powered ’52 Ford.

High school buddy Gale Tuggle remembers Mullins’ mom, Mildred, being puzzled as to why the area’s teens were always revving their engines at her when they pulled up to a stop light.

Tuggle, a frequent guest at the Mullins house, remembers, “Mildred said, 'I don't know what it is about the younger generation. Every time I stop at a stoplight, all these young guys next to me are revving their engine, and the moment the light changes, they just burn right off.’

“Bill had put a three-quarter cam in the car, and it had that lope in the idle. Anybody that knows anything about engines knows that it's been hopped up and they think Mom is gonna peel off as soon as the light goes green.”

Mullins had already lost his father, a local police chief, in a household accident while Bill was in high school, which led him to make those kinds of decisions without correction from a male parental figure who would have known what mischief car-hungry teens can get into.

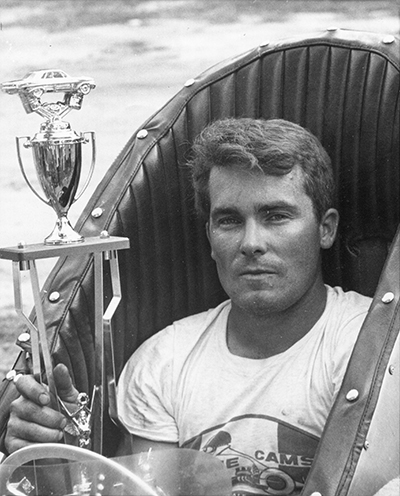

Mullins raced his mom’s Ford for a number of years — and even a twin-engined Triumph motorcycle that landed him in the hospital after a trip off the top end — before taking the knowledge he’d accumulated, he and his brother Bob dived into the Top Gas class in 1959 with a carbureted Oldsmobile motor and a high-gear-only combination that quickly worked his way into the nine-second zone.

“They wouldn't let me run against the dragsters that started popping up in the area, so I started to think about a dragster myself,” said Mullins in a 1981 NHRA National Dragster profile. “I'd seen pictures of the cars out in California and got interested."

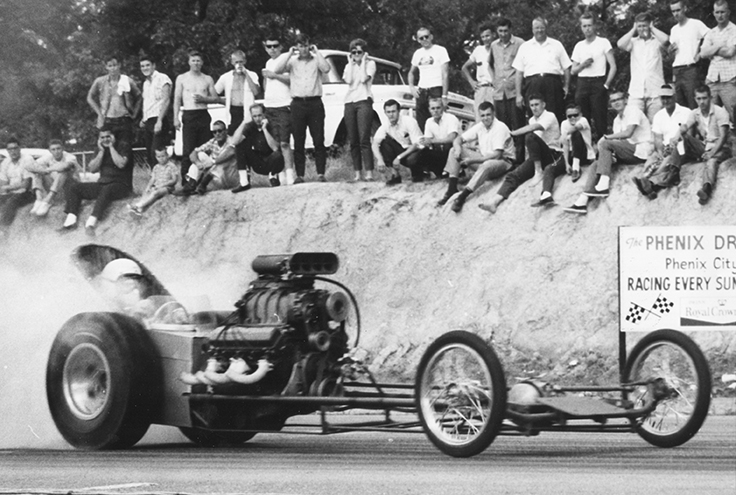

A new machine built by Chassis Research helped him to low-nine-second clockings until he crashed the car in 1961. Mullins built another car, but it took him four years to regain his form and start winning regularly in 1965 and 1966 at local southern races.

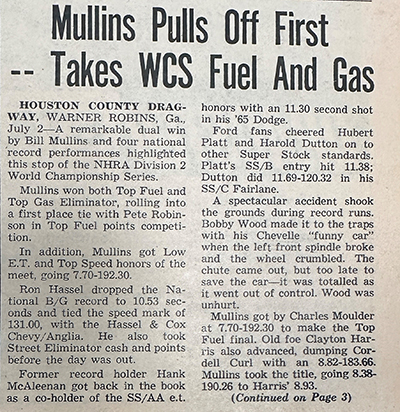

About this time, Mullins also began dabbling in Top Fuel with a Chevy-powered dragster and pulled off a rare double win in Top Fuel and Top Gas at the summer 1967 Division 2 World Championship Series race at Houston County Dragway in Warner Robins, Ga., which later became better known as Warner Robins Dragway (and this “Houston,” by the way, was pronounced not like the Texas city but as ‘House-ton,” in case it comes up in your casual dinner conversation sometime).

In winning the four-car Top Fuel field, Mullins beat Charlie Moulder in round one and fellow Alabaman Clayton Harris in the final, 8.38 to 8.93, in a race in which neither hit their stride (Mullins had earlier set low e.t. at 7.70). Mullins then went on to defeat Don Powell in the Top Gas final, 8.46 to 854.

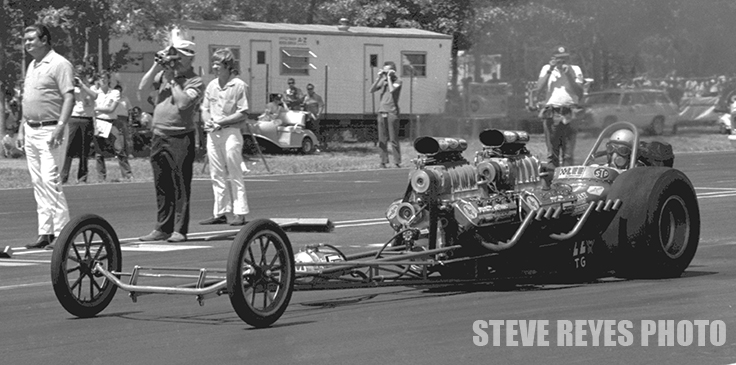

In late 1967, impressed by the success of John Peters’ twin-engined Freight Train Top Gasser, Mullins built his own twice-motored machine, using Chrysler power instead of the Chevys campaigned by Peters.

“I figured if one Chrysler could almost beat one Chevy, why couldn’t two Chryslers beat two Chevys,” he reasoned.

The new twin was promising, but a flat tire caused the new car to flip and encounter severe damage on only its fourth weekend out.

When questioned about his enthusiasm for the sport despite his numerous setbacks, the good-natured Mullins told NHRA National Dragster in 1971, "It's just the competition and the fact that I can always look forward to next week. No matter what [happened] on the weekend before, there's always the next time.”

While working on rebuilding his twin, Mullins jumped into John Reed's BB/Gas dragster that he had raced in Comp eliminator in 1966 and won class at the NHRA Springnationals two years straight.

The twin finally returned to the track at the 1970 Gatornationals, but the powerful combination had a nasty habit of breaking rear ends, and it wasn’t until the following year that Mullins hit his stride and won his first national events, the 1971 Springnationals at Dallas International Motor Speedway, where he defeated Walt Rhoades in the final round.

(Discounting the large number of drivers who have won in Top Fuel and Top Alcohol Dragster, Rhoades, who also recently passed, was the other driver to win in both Top Gas and Top Alcohol Dragster, and Jimmy Nix and Bob Noice were the only other ones to win in Top Gas and Top Fuel. As mentioned previously, no one other than Mullins ever won in all three dragster classes.)

Later in 1971, Mullins was credited with the first-ever six-second run on gasoline at a major NHRA event at the National Open at National Trail Raceway.

But Mullins and his dwindling amount of peers soon found themselves without a class after NHRA dropped the Top Gas class beginning in 1972 as NHRA took note of low car counts and shifted the Top Gas cars into Comp eliminator. Many, like Mullins, had no desire to go back to index racing and either quit or went into Top Fuel.

"I think the twins really killed the class,” Mullins admitted. “They took the incentive away from the single-engine cars, and they stopped being built. It broke my heart because [I] knew at the time I had the fastest car in the country on gasoline, but it was probably for the best that they eliminated it because riding behind one engine was dangerous, but riding behind two was really dangerous. You got oil on your goggles sitting back there, and the car was heavy. We didn't have ballistic blankets on the blowers then, or puke tanks, or engine diapers."

Mullins was out of racing until a trip to the 1978 U.S. Nationals with friends Mickey Cox and Bob Amos. By then, the Top Alcohol Dragster class had become well-established.

“It was like taking an alcoholic to a bar,” he said. “I saw how nice the rear-engine cars looked and how safe they were. I had to go racing again.”

Mullins’ weapon of choice for Top Alcohol Dragster — a small-block Chevrolet — surprised everyone.

"I wanted to go with the Chrysler — I had a garage full of them, but they weren't the aluminum type that everyone runs — so to avoid following the crowd, we decided to run a Chevy small-block,” he said.

“I was always impressed with the way Dale Hall could get his small-block to run and wanted to be able to meet the challenge, but we found out that you can't lean on a Chevy like you can a Chrysler. You’ll burn a piston in the Chrysler, but you'll blow the bottom out of the Chevy.”

In 1981, a decade after his first national event win, Mullins won the NHRA Cajun Nationals, where he defeated future Top Fuel champion Joe Amato in the final. Amato had qualified No. 1 with a 6.67, but Mullins set low e.t. in eliminations with a 6.62 and beat Amato in the final, 6.67 to 6.70. The engine with which he won was a 340-inch small-block Chevy with a new prototype injector set up by another former Chevy veteran Tony Garcia. The car ran a two-speed that was slow off the line but really came on in high gear.

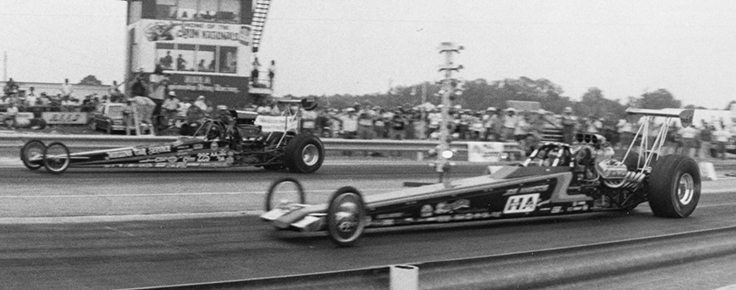

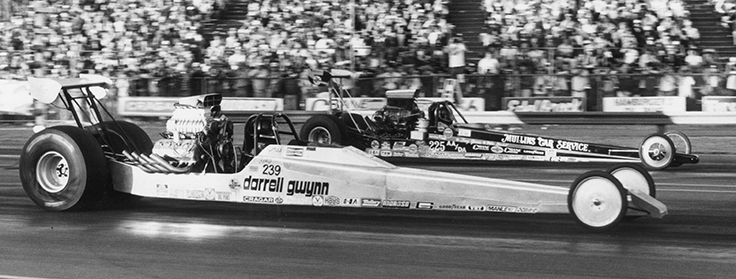

Southwest NHRA legend Darrell Gwynn remembers Mullins and his screaming small block well as he cut his teeth racing against Mullins in the early 1980s in Top Alcohol Dragster.

"He ran all the Division 2 races back in the late ‘60s and ‘70s with my dad, and I always got to be around that twin-engine car, which was just iconic in the south,” remembered Gwynn.

“When I started racing, we chased each other all over the country, but one of my proudest moments was with Bill at the 1981 Golden Gate Nationals in Fremont [Calif.]. The West Coast guys, they would always talk [crap] back in the days about me and Mullins running 6.60s back here in 95-degree weather when they were all running 6.50, and they're like, 'Wait till they get out here; we're gonna whip their asses,’ then me and Mullins went to Fremont — it was my first-ever trip to California — and we qualified No. 1 and 2, were both in the final, and ran the quickest side-by-side race in history."

Gwynn won that tussle – handing Mullins one of his seven career runner-ups to go with his three wins – leaving slightly on Mullins and racing to a tight 6.41 to 6.43 victory.

“That small block, it weighed a million pounds less than my car did at the time, and he's got a two-speed with a small block, and I had a three-speed with a late model [Hemi], but we didn't vary two feet from each other from the time we left the starting line to the time we got to the finish line,” said Gwynn, still sounding awed more than 40 years later. “It just was so weird to me that with two different combinations, they were so equal. We were both pretty proud of that moment.

“He was so tough with that small-block Chevrolet; he had that combination winning long before [five-time world champ Rick] Santos did. I always said that car was held together with hose clamps, tie wraps, and silicone, but he did whatever it took to make that thing go. He'd work on it all night long at those Division 2 races. He was a simple man. He had a little mechanic shop called Mullins Car Service, and he'd work on everybody else's car during the day and work on his car at night, and his car was badass fast. He was true grit. That guy was tough as nails and a workaholic.”

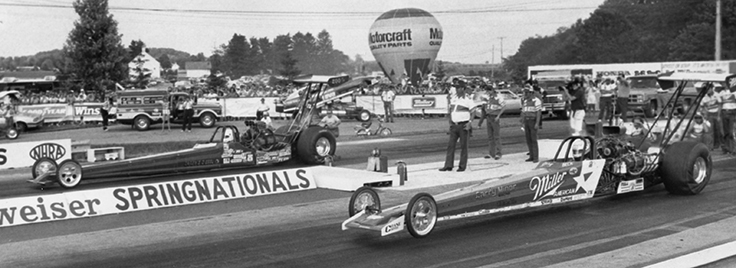

Mullins’ final national event win came in Top Fuel, at the 1985 Springnationals in Columbus, Ohio, where he beat four tough drivers — Dan Pastorini, Don Garlits, Dick LaHaie, and Gary Beck, at the wheel of Larry Minor's Miller American entry — to put Carey’s dragster in the winner’s circle.

Mullins, who people forget was the third driver in history to exceed 260 mph — behind only Amato and Garlits — and also was among the first Top Fuel drivers to go back to direct-drive in the late 1980s, even though Gene Snow usually gets the credit.

"I started running like that at the end of 1986 and ran almost all of 1987 without a transmission," Mullins told me for a NHRA National Dragster story on direct-drive in 1996. "The problem was I was doing it on my own. I didn't have any help; didn't have any money. I was using a two-disc clutch with six fingers — no lock-up — and I couldn't afford anything else. I had to run used tires, and I felt that high-gear-only would help me get traction with those tires.

"I tried to talk several people — Tim Richards, Lee Beard, and guys like that — into doing it in 1986 and '87, but they all had good two-speed combinations, and I wasn't running that well because I didn't have a fuel system worked out and had no money to buy one, so I couldn't convince them."

As Head did later, Mullins tried to disguise his doings by running the input shalt through a hollowed-out transmission case, which didn't help him earn his due credit.

"If you ask enough people, they tell you that I was the first," said Mullins. "It's interesting that 'dumb ol' me' could contribute something to what's still going on."

Mullins was inducted into the Division 2 Hall of Fame in 1995.

Grandson Kevin Lindell remembered him on Facebook: “The man, the myth, the legend. From hearing how he would carry an engine block on his shoulder around the garage to racing twin-engine, alcohol, and Top Fuel dragsters. He was a man who would challenge anyone to an arm wrestling or Indian wrestling match. … The stories I’d hear growing up made him sound superhuman, maybe that’s why some people called him Superman, but I called him Pa. I feel like if you knew him, you had a crazy story to tell about him.

“His love for racing and being healthy influenced me for much of my life. Without him, I probably never would have had the desire to have a Mustang, and I certainly never would have started lifting weights. He’d always check on my progress with staying in shape, and I’d always remind him that I was still trying to get on his level. He’d chuckle and tell me I passed him long ago, but let’s face it, he’ll always be the man!”

(For more great remembrances from his family, including children and grandchildren, click here.)

After losing contact with his old high school buddy when he went off to college to play baseball and later to Canada to play pro ball and coach, Tuggle reconnected with Mullins years later and remained in close contact with his old friend until Mullins' passing.

“I went to a couple of races with him when it was local because that was easy, but once we graduated, I went to junior college to play baseball and football and then got a scholarship to play baseball at Florida State and Bill got heavy into drag racing and just kept building him higher and higher in the drag races. When I was at East Central Junior College in Mississippi, I got into automotive engineering, and we felt like we could continue scratching each other's back on what he was doing, but Florida State didn’t have automotive engineering, so I just concentrated on sports.

“My career took me so far away that I didn't get the joy of some of the really great times that Bill had and the reputation he got with automotive building and his racing. Our two careers were happening basically at the same time and about all we did was keep in contact with each other by phone or letters. In the mid-‘90s I left Canada and moved to Pagosa [Colo.], I begin to touch base with Bill again. We kept in touch almost every month or every other month with phone calls back and forth. Anytime I could, I jumped on my [motorcycle], and in 24 hours I could be sitting there at my mom and dad's supper table in Alabama. Bill and I would meet at his shop or at Barber [Vintage] Motorcycle Museum, and we’d just sit and [BS] for a while.

“He was as close to being what I and other friends would have called a Southern Gentleman. He was very soft-spoken, but if it came to something where he had to flex muscles or in any way to defend his honor or anybody else's honor, there was no doubt in anybody's mind that you might have stirred up a hornet’s nest. He was just a great, great person.”

Gwynn couldn’t agree more.

“He was true grit,” he said. “I always really, really liked him, and I never wanted to make him mad because that guy was built like a Mack truck. Bill Mullins is a guy I'll never forget. He really was a good guy. He would give us a shirt off his back. He would do anything for you. And I got to spend a lot of time with him back in the day, and he was a guy I always looked up to.”

Current Top Fuel racer Will Smith, whose career path from Top Alcohol Dragster to Top Fuel followed the trajectory of fellow Alabaman Mullins, was close to the man, too, and even chose Mullins’ permanent number, 200, as his own.

“Me and Mr. Bill had a special bond,” he shared on Facebook. “The stories he shared and the knowledge he shared with me over the years have been so awesome. One of my greatest times at the dragstrip was when he came to Atlanta Dragway for the final NHRA event of the track to be a part of our team for the weekend when I was driving for Hirata Motorsports. He told me that was one of his best times he ever had at the racetrack. Man, did that mean the world to me. We spent hours and hours on the phone talking. If I didn’t call him, he was calling me to ask how racing was going. There wasn’t a call we had or a time spent together that we didn’t depart without telling each other we loved each other.

“Mr. Bill, thank you for all you did for out great sport over the years. You were always a great guy and a fierce competitor on the track. You were a real racer and put everything you had into racing. Thank you for always being in my corner from the time we first met. Thank you for being Bill Mullins and for being one of my best friends. It’s a true honor to carry the number 200 in Top Fuel for you and for keeping it in the state of Alabama.”

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator