Frank Mancuso: Some good trips and some bad ones for the 'Travel Agent' driver

When it comes to 1970s and ‘80s Funny Cars, especially the privateers and “low-buck” cars, I know I have a “West Coast bias.” Guilty as charged. I grew up at Irwindale Raceway and OCIR, so you can’t blame me, but I know that for every Jeff Courtie, every Mike Halloran, every Rodney Flournoy, there’s an East Coast equivalent, a guy that was a fan favorite who mostly ran match races but also was known to run some national events, guys like Joe Jacono, Les Cassidy, Tim Kushi, and today’s subject, Frank Mancuso.

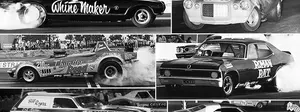

Fans may remember him as the driver of Ron Leaf’s Vega and, after that, the Travel Agent Funny Car, which got a lot of press for two unfortunate accidents but nonetheless was an East Coast standout and past Division 1 champion.

I first “met” Frank back in 2007, in the first year of this column when he emailed me, and had emailed back and forth numerous times throughout the years. After he read my column on drag racing books, he messaged me recently to talk about his book, and, with everything I know — and everything I wanted to know — about him, I thought he’d make an interesting topic.

We all know that back in those early days, it wasn’t uncommon for a driver to leap right into a nitro Funny Car with little or no experience. The cost to compete was so low that Funny Cars quickly proliferated, but Mancuso actually worked his way up from the doorcar ranks before he started to burn a little nitro.

“I grew up loving cars,” he remembered. “When I was about 12 years old, I traded a guy some silver dollars for a flathead motor. I had no tools, so I took it all apart with hammers and chisels, and a screwdriver. I wanted to have a piston. I had never felt a piston in my hands. My hands got ripped open and were black from grease, but I finally got a piston out of it. I washed my hands with Tide, but, oh my God, my mother. I ruined her house with grease and oil on her towels. They got filthy. Yeah, I was possessed by cars and motors and all of it. I probably bought every magazine about cars. I read Jim McFarland religiously.

“The day I graduated high school I opened up a speed shop to modify cars. I was doing rear ends, cams, and heads for people. I bought a ’68 Z28 brand new for $3,000. I drove it home, and that was the only time I ever drove it on the street. I took it apart and raced it the next weekend.

“I ran Stock and then Super Stock and then Pro Stock. It was just local stuff. I think I raced on Long Island and Dover [Dragstrip] mostly and did pretty well and actually got a lot of trophies. NHRA wouldn't let me run Pro Stock [at national events] because my roll cage wasn't big enough — I made all my own stuff — but I raced against guys like Bobby Lagana, who had a Pro Stocker, too. The funny thing about Bobby was that he would put a bunch of batteries in the trunk so he could do giant wheelies. He was always a showman.

“Later I owned a speed shop, First Performance, in Eastchester, N.Y., which was a pure drag racer’s town,” he remembered. “Most of us raced on the streets or at Dover. Into my shop came people like Bobby Lagana, Vic Ferris, Brian Dowling, Dick Moroso, and Ron Leaf. Leaf and I became best friends.

“The funny thing is they all liked Funny Cars. We learned what we could out of National Dragster, but that was about it, but Funny Cars were the topic of the day in the speed shop every night. Ronnie Leaf was crazy about Funny Car racing. He had an inheritance from his father, [who] died, and cashed it in for next to nothing to get the money to go Funny Car racing. Then he went out and bought a brand-new Ford Thunderbird that he financed through Ford. He then drove it across the street to a used car lot and sold that $3,000 car for $1,500 cash, because back in those days there were no titles or pink slips or anything. It was insane.

“Ronnie bought the ex-Stampede Funny Car, and Brian Dowling attempted to make a pass at Dover in it. After a half pass, the car was parked in Ron’s yard, and then he sold it and bought a new Logghe [-chassised car]. He also parked it n his yard and attempted to mount the body and do the tin work. Every night in my shop we would tell stories. We got in dribs and drabs, and Funny Cars always were the subject, and Ron always asked me to help him with his.

“Brian, Vic, and Bobby all wanted Funny Cars, and eventually, Bobby and Vic got them. (Twilight Zone and The New Yorker, respectively.) Ron and I would take his car to a public beach parking lot and try to start it. We were clueless. We watched other cars at the races and were sure we could figure it out. First, we ran it on gas, then we tried a bit of nitro, and, little by little, it would run. Ron started it and set it on the ground, and I drove it around the parking lot until the cops kicked us out.”

Mancuso was still running Pro Stock, but Leaf kept asking him to get involved with the Funny Car. Eventually, they rented Westhampton Dragway, and Mancuso, who didn’t even own a firesuit, made a successful run wearing a T-shirt. Leaf was gung-ho after that success and struck a deal with Woody Gilmore for a new '72 Vega Funny Car.

“We somehow managed to get it together and went to Raceway Park for my fuel license, which Vinny Napp signed for me. (He needed cars for his shows),” recalled Mancuso. “We went to the [1973] Summernationals, and unfortunately, on my first qualifying run, I did a wheelie at half-track, so we went home and put on wheelie bars, which were not popular in the day — racers called them ‘training wheels’ — and we match-raced once or twice, then went to Sanair.

At Le Grandnational, Mancuso and Leaf qualified an impressive third on the Sanair Dragstrip with a 6.730, behind only Paul Radici (6.627) and Dale Emery (6.714) and ahead of guys like Leroy Goldstein, Tom Prock, Harlan Thompson, and Paul Smith.

Mancuso got a bye run in round one when Smith broke then ran a steady 6.77 to upset Radici in the semi’s before squaring off with Emery, who was at the wheel of Jeg Coughlin Sr.’s Camaro. Emery eked out the win, 6.70 to 6.80, after Mancuso blew the rear end, but the world changed for Mancuso.

“All of a sudden I was getting products in the mail and mentioned in National Dragster,” he recalled. “The NHRA guys called me ‘Frank who?’ “

The team also ran a series of successful match races, but, despite that success, Mancuso temporarily lost his ride in the Leaf car to Lagana, but the duo later reconciled in 1977 and qualified for the Summernationals but lost to Tom Hoover in round one.

“Ronnie approached me about driving his car again, but it was a mess,” he recalled. “The body was cracked and broken and must have weighed 500 pounds, but, you know, I was desperate to do it. I didn't want to do it. I was just so mad at him still, but yeah, I did it.

“After that, he won some match races before I burned it to the ground. I was a bit behind the [tuning] curve after missing those few years, and that was pretty much it for me and Ronnie.”

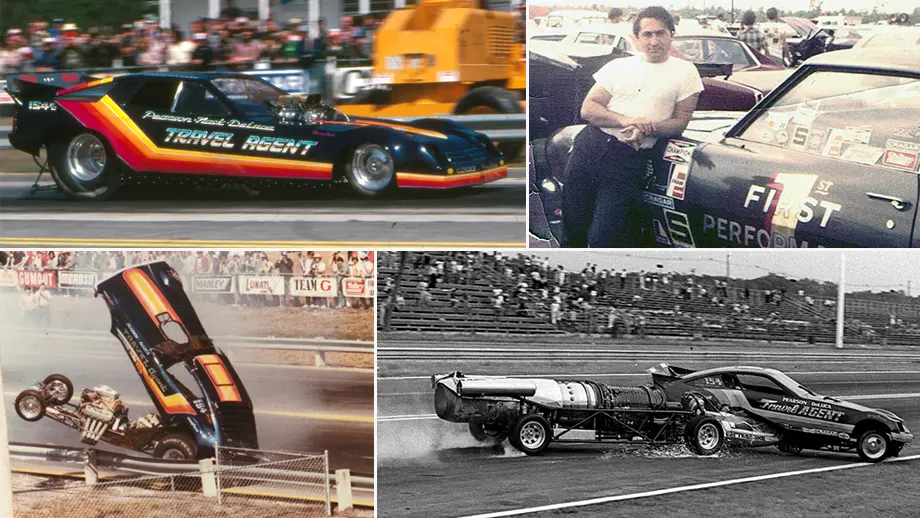

The following year, Bobby Nask and Pete Pearson bought Bob Barry’s “Rolling Thunder” Monza, rechristened it as “Travel Agent,” and hired Mancuso as their driver, and thus began a very star-crossed 1978 season with a spectacular incident at the Gatornationals.

On his first qualifying pass, Mancuso got loose, crossed the centerline, and went backwards over the guardrail into the photographers’ area. Fortunately — as can be the case at Gainesville Raceway — heavy rains had flooded a portion of the area so it was unoccupied when the Travel Agent made an unexpected landing.

“It was a mad thrash to get it to Gainesville, and I had it on kill because I think we had one shot to get it [qualified],” he remembered. “I tried too hard, the headers dug in, and I flipped it over the guardrail. [TV announcer] Steve Evans got mud all over his suit interviewing me. He was about a foot in the mud with his suit on and his good shoes, and he's trying to interview me standing in the freaking mud. I felt so bad for him.”

The team went home and rebuilt, and was back in action at the Summernationals, where their 6.41 was good only for 20th (but were joined on the DNQ list by next year’s world champion, Raymond Beadle) but then went on a tear, winning three straight Division 1 races and the Division 1 championship.

His victory at the Maple Grove Raceway event was truly bittersweet as it came after the passing of good friend Dodger Glenn, who was fatally injured after defeating Bruce Larson in the semifinals. Mancuso, who had bested Tom Prock and George Johnson to make the final, made a sad 13-second solo for the win.

“I was at the end of Maple Grove when a ball of fire just missed hitting my car as it went flying into the woods,” he recalled. “He went into the woods, and it was so dark no one could find him. We were sorry when we finally did. Poor frickin’ Dodger. We loaded up to go home, and [Division 1 Director] Darwin Doll came over and said, ‘Frank, you’ve got to really make another run because it won't count unless you do.' We had to take the car off the trailer and get it to the line, but I just putted it down [the] track. That was a bad deal.”

But Glenn had left him with some good advice that would pay off not long after when Mancuso was pitted against the Earthquake jet dragster of Mike Evegens for a match race at Englishtown.

“Before his unfortunate run, Dodger and I were talking in staging, and I told him about my upcoming match race with the jet,” Mancuso said. “I wasn't very happy about it, but I needed the money and was doing it as a favor for Vinny Napp. Dodger told me, 'Whatever happens, don't let the jet get in front; the kerosene [fuel exhaust] will detonate your blower,' ” Mancuso remembered. “I took those words very seriously.”

Against Evegens’ jet, Mancuso made sure he left first but got loose. Not wanting to get behind the jet and risk engine damage, he pedaled it but lost the handle and crossed right into Evegens’ path, as you can see in Norman Blake’s epic sequence below.

“I remembered Dodger's words and stayed in the [throttle] too long, and it veered right just as it did in Gainesville,” he said. “I was hoping [Evegens] would pass behind me, but he hit me in the side, he pushed it right into the guardrail.

“I broke both feet, and my right leg was nearly severed. I remember waking up on an operating table and the doctor was trying to put my leg back on. Dr. Ang had worked on all these guys in Vietnam and knew how to connect all the nerves. I had two operations, and before the second one, he told me I'd be better off without the leg. I said, ‘No way. I want to keep my leg,’ so he worked on it and worked on it, [and] he got enough of it back together that I was able to keep it.

“After I recovered, I looked at the bits and pieces of that car and found that one inner tire was about three inches larger than the other.”

Mancuso was back in action in 1980 in a new Travel Agent Omni, one of the last Funny Cars built by legendary Pat Foster. The car was named “Best Appearing Car” at the Summernationals and qualified for the field but lost in round one of Ed McCulloch.

“NHRA was the greatest,” he said of his reception. “I met Wally Parks, and he shook my hand and welcomed me back. What a great feeling. What a great guy. Wow, it almost brings tears to my eyes even now.”

The rest of the early 1980s followed form, with a string of either DNQs or first-round losses plaguing them in the face of better-funded teams.

“Bobby Nask, Spence Thomson, Fred Ludwig, and I all had regular jobs and did our best to race, building a tractor-trailer and qualifying now and then, but the sport was getting beyond our limited ability to keep up,” he admitted. “All those long lapses, you lose information, you have no clue what's going on.

"We were actually one of the first to experiment with a high volume of fuel setup. Sid Waterman kind of took me under his wing, and he gave me a big high-volume fuel pump. We got special valves that I would have to work as [I] staged the car to dump a lot of fuel in the motor, but never had two mags to light it, let alone computers or lock-up clutches. It was pretty far advanced, but we were not quite there.

“My last pass was at the 1984 Summernationals. We burnt some pistons and had no replacements. I was lost. We had two pistons. I was clueless at that point. It had all passed me by. I only wish I never had those long lapses from competing. I made relatively few runs, but it was a hell of a trip.

“Somehow I outlived many of my friends, but the lessons I learned from drag racing and the great people taught me lifelong lessons about not-so-nice people and being willing to take them on, which leads me to the story in a book I wrote about how those people destroy our lives and pollute our world with their toxins."

The autobiographical book, Evolution of Pollution, chronicles both Mancuso’s racing career and his post-racing life, including his purchase of the Echo Bay marina in New Rochelle, N.Y., that turned into a nightmare and a 20-year legal battle after Mancuso discovered it to be a Superfund dumping ground for carcinogenic PCBs. Mancuso had bought the property hoping to turn it into a successful business to fuel a return to racing but instead ended up losing everything in the legal battle, including two houses.

“My parents got cancer, my dogs got tumors, so I sued. I spent every penny I have in the world trying to get them to court, but it never went to trial. I lost everything. That's what made me write the book.”

But there is a happier ending. Mancuso was that dad who actually bought his 9-year-old daughter, Deanna, a pony she asked for, which led to an amazing thing and a legacy that will live on beyond Mancuso’s racing career.

“My family was devastated after the lawsuit, but my daughter liked horses,” he said. “I had to scrape every penny I could get together and bought her a horse. And from that horse, ultimately, I started a horse rescue, Lucky Orphans, which today is probably one of the biggest horse rescues in the country, and she runs it now. She has 60 horses and works with [soldiers] and cops who have mental issues and handicapped kids and puts them together with horses that can help people with their problems.

“Drag racing was the best days of my life,” he concluded. “I mentioned NHRA in the book and what great people they are and how they always bent over backward to accommodate me. I never met such nice people. I mean, even you calling me after all these years. I was truly blessed.”

I thanked Frank for the time and the opportunity to tell his wonderful story and to continue my mission to share stories of racers from all levels of the sport.

Even if they’re not from the West Coast.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator