Book review: Drag Racing's Warren "the Professor" Johnson

A lot of people love Pro Stock. Kelly Wade LOVES Pro Stock. The former NHRA National Dragster staffer turned drag racing public-relations pro began her passionate affair with the class early in her two-plus-year stint on my staff and only grew as she befriended everyone from the elite of the class to the part-timers, beguiling them with a combination of unfettered passion, unerring positivity, and an uncontainable joy that flowed from her like the sweet notes of a 500-cid engine. She also loves people and getting to know what makes them tick.

All of this made her the perfect person to tackle the daunting task of chronicling the life and times of “the Professor,” Warren Johnson, one of Pro Stock’s best -– and probably least understood –- racers. W.J. still holds the record for most Pro Stock wins (97) and has a string of performance diplomas for things like being the first to break the 200-mph barrier and (as crew chief for son Kurt) the first six-second Pro Stock pass.

Early on in the book, Drag Racing's Warren "The Professor" Johnson: The Cars, People & Wins Behind His Pro Stock Success, Wade makes the astute observation (later echoed by Johnson) that, for W.J., “conversation without purpose is just as invaluable as making a pass down the quarter-mile with no intention of winning,” yet based on his candor in the book, he clearly thought of sharing his life story as a winning project.

Wade conducted the interviews both in-person in Sugar Hill, Ga., and over the phone from her southern California base, and the Johnsons certainly were accommodating.

“I made several trips to see them, to sit with them and go to dinner with them and even stayed at their house; they were so gracious," she said. "And I really misconstrued how funny he is. Early in my journalism career, I didn’t wrap my brain around it, mostly out of reverence and fear, because he was so big and so important in our sport that I couldn’t really relax enough to get his humor, which is very dry.

“It was also very neat to see him just being him. He and Arlene eat at the same restaurant, a little bar and grill type of place, six days a week. [On the seventh day, they go to a Mexican restaurant.] Seeing him interacting with people who don’t know drag racing, who do not want to question him about how an engine works, he’s just so jovial. All of the girls that work there, the bartender, everyone, greets them. It’s like they live there, and everyone loves them. They’re funny and bantering, and it’s this whole other side of him that no one knows.”

“Back home, I’d call him whenever it fit my schedule because he’s literally in the shop every day from 7 in the morning until 7 at night,” she said. “They pretty much gave me an open-door policy to call him when I needed to.”

The book recounts in-depth Johnson’s rise through the Pro Stock ranks, a tough course in learning how to race with, against, and eventually beat heavyweights like Bob Glidden, Lee Shepherd, Wayne Gapp, and Bill Jenkins. From humble beginnings with a ’57 Chevy through his first foray into Pro Stock with a Camaro he bought new off a dealership lot and quickly gutted through the tough sledding on the mid-1970s and his twin IHRA championships in Jerome Bradford’s Monte Carlo (W.J. grew tired of NHRA’s ever-shifting engine “weight breaks” and took his efforts elsewhere). It chronicles the glory years of the 1990s, the breaking of the 200-mph barrier, all of the championships, and stats, and so much more.

While Johnson experienced great success in his first decade in the class, he didn’t win an NHRA event until 1982, in his first year of a career-changing move to Oldsmobile, and the struggle was real and recounted in true-to-form honest recounts by W.J.

Of beginning his long journey and the hurdles he knew lay ahead, Johnson said, “I guess I looked at it from the perspective of an investor: they know they aren’t going to make a million the first day; they had to learn to invest. It’s the same thing with racing.”

Johnson has never been short on opinion, and although his full nickname is “the Professor of Pro Stock,” W.J. can intelligently and informedly speak on just about any topic, and proof of that comes out in the book, especially in the 33 “The Professor’s Way” lesson sidebars generously sprinkled throughout the book, where Johnson shares pearls of wisdom that on the face are about running a race car but also run true for most things in life. While he can come across as gruff and surly in public interviews, the W.J. we see here is funny, introspective, and, above all else, professorly in his approach to everything.

Here’s one of them: “I don’t really believe in destiny. God designed us all with equal intelligence and opportunity. He also gave us two ears and one mouth, which means you should be listening twice as much as you’re talking —and sometimes, that’s how you find opportunity. My attitude has always been, do whatever it takes using whatever you have, and if you’re only going to do something halfway, there’s no sense in doing it at all. How much desire you have and how you cultivate your opportunities determine what the end result will be. How much sacrifice are you willing to endure to achieve your goals?”

The book is packed with little gems. Here are a few of my favorites.

Asked if he was nervous when he made his NHRA Pro Stock debut on the grandest of all stages, the U.S. Nationals, in 1971, Johnson dismissed the absurd notion the way someone might bat away a fly.

“Nervousness is usually the result of a lack of preparation, and being nervous is a waste of time and energy,” he professed.

Johnson says he never had a favorite of his many race cars, explaining it as only he can: “A Pro Stock car was nothing but a 9/16 wrench, the most common in the toolbox. It was a weapon that I used to make a living. There was never a car I fell in love with.”

While it’s easy to dismiss these types of comments as cocky, Johnson was certainly someone who could walk the walk as he talked. The book also has a great section discussing Johnson’s numerous rivalries over the years with the likes of Shepherd, Glidden, and “the Dodge Boys,” Darrell Alderman and Scott Geoffrion, and, of course, talks about W.J.’s battles with his former crewmember and protege, Greg Anderson.

“When Greg came to work for us, he didn’t know a piston from a petunia,” Johnson pointedly remembers, as well as the week he sent Kurt and Anderson to Roy Hill’s Pro Stock school to get a better understanding of the class. “They were there damn near a week," he remembers, still quite perturbed. “It was a week of two people out of the shop not doing anything, but we had to all get on the same page if we were going to move forward.” That’s a Greg Genie that W.J. may regret letting out of the bottle if/when 95-time winner Anderson is able to surpass his 97 wins.

The book is a delight as it also sheds light on the vast contributions made by Johnson’s wife, Arlene, and son, Kurt, neither of which can be overstated, and Arlene’s contribution to this book beyond her explanation of life on the road with her never-rest husband.

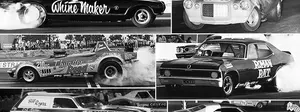

In addition to Wade’s poetic and probing prose, the book's greatest selling point may well be the vast treasure trove of photos taken by Arlene during those early years. It seems that any time that her husband did anything, the camera was up and ready. We get to see a young W.J. celebrating wins, working on his cars, and the cars and engines themselves in varying degrees of preparation. There’s also plenty of pro photography from the likes of Steve Reyes, Auto Imagery, and more, showing some of Johnson’s great machines in action over the decades.

“When W.J. was working, I’d go to their archives and sort through boxes and boxes and boxes of photos. It was unreal how many photos there are,” Wade said, still in awe. “Arlene not only liked to take photos, but she always seemed to have a sense of wanting to catalog not just his process but drag racing as well. She was soaking up the entire scene.”

There’s enough tech talk in the 178-page book to keep any gearhead happy, enough stats to make Bob Frey smile, and W.J. fans will certainly enjoy following the rise of the $1.39-an-hour welder to Pro Stock giant.

Wade generously mentions me in her forward to the book and says she hopes the book makes me proud. It does. Good job, KW!

You can buy the books just about everywhere online, including Amazon.com and the CarTech website. Enjoy the free chapter preview below.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

![]()

Chapter excerpt:

FROM MATCH RACING TO A MAJOR SPONSOR

Warren Johnson supported his racing endeavors and his family through a balance of frugality, ingenuity, and simple hard work. For a gentleman who enjoyed racing and understood the formula for making money while doing it, opportunities were plentiful in the early years.

“I never considered it particularly difficult,” admitted WJ. “Heck, if you can come out of northern Minnesota, you can survive racing. We went match racing, pro racing, all the UDRA stuff. Then, whatever it paid, you put it in the bank and were that much further away from poverty. I looked at match racing as an avocation, not a vocation. This was my hunting, fishing, gardening, and bowling all wrapped up in something with four tires on it.”

Between the UDRA circuit in the Midwest, in which Johnson competed in 20 events and was named the Rookie of the Year in 1972, and the plentiful amount of racetracks scattered around the local area, WJ and his brood participated in a tremendous amount of match racing.

He brought home a tidy sum each week. Although they didn’t spend much time at home, and WJ was never left with any spare time, as he worked tirelessly to make what he had better. The circuit evolved along with the popularity of Pro Stock. In 1972 and 1973, it was on full blast with events scheduled throughout the week by racetracks with highly effective promoters who repeatedly packed the house with folks who fiercely appreciated Pro Stock.

“They got 19,000 people in Minnesota Dragways one Sunday, and we raced John Hagen in his factory-backed Mopar,” said WJ. “When those two cars were on the starting line, you could hear a pin drop.”

John Foster Jr. was just a teenager when WJ was a regular at Minnesota Dragways. He recalls getting a read on the future legend relatively quickly as someone who didn’t mince words when something was on his mind.

“He was a very spirited competitor,” Foster said. “As best I remember, he spoke his piece, and you always knew where he stood. He was very professional, even then, and he wanted everyone else to be very professional too. He was a good racer and didn’t appreciate people who didn’t take it as seriously as he did.” WJ enjoyed competing at the facility, whether it was for a match race or a UDRA event. Minnesota Dragways was unique in that it had oversized safety zones, including a 3/4-mile shutdown that extended the length of the surface to an entire mile from the starting line to the end of the track. The track was wide with no guardrails or cement retaining walls, and it was one of the first to put on a four-wide show. The facility did this out of necessity because with 600 or 700 cars entered, racing four across was the only way to expedite the process enough to get everyone through eliminations. The stands sat well back from the racetrack, but they would be filled for races that WJ ran, and cars would be parked well into the surrounding woods.

The racetrack was managed by Foster’s parents, John Sr. and Marjorie Foster, and he worked his way into being something of an official track photographer. He drafted a catalog of images from the likes of WJ, John Hagen, Bill “Grumpy” Jenkins, the Sox & Martin team, Dave Strickler, Gapp & Roush, and many others who raced at the family’s drag strip.

The match races between WJ and John Hagen, though, were among the most raucous. The fans in the stands backed their preferred brand: Johnson in the Chevrolet and Hagen in the Mopar. The announcer would rile the crowd, eliciting cheers from the Chevy loyalists that would be answered just as enthusiastically by the throngs of Mopar fans.

“It was a fun rivalry,” said Foster. “There were never any staging issues or any of that kind of stuff that goes on today—they just respected each other as professional racers. It was good, clean racing, and everybody loved it.” WJ was careful with his winnings from Minnesota Dragways and every event he attended. He padded his financial stability with a healthy dose of resourcefulness. He only purchased the parts that he needed and fabricated anything and everything that he could. The Johnson family didn’t take vacations or spend lavishly on household items. They recognized that their fiscal well-being was in their own hands; sponsorships weren’t common, and large sponsors were unheard of at that time.

“You’d have a few guys [who] gave a little bit of money here or there, but it didn’t really amount to anything other than helping to pay the bills,” WJ recalled. “But I just said, ‘This is what I’m going to do, and dammit, I’m going to figure out a way.’”

MID-1970S MARCH

When WJ committed to full-time racing in 1976 without a backup plan, he began filling in races wherever he could, match racing, running the AHRA circuit, and entering all eight of the NHRA events. Midway through 1975, driving the 1974 Camaro that came to be known as The Incredible Hulk, WJ had already begun to garner attention in respected circles.

His success and efforts gave fresh life to the Chevrolet Camaro in Pro Stock, and a large part of the strides that he made early on was his eagerness to ask questions, listen, and learn. He continued to develop relationships with entities that catered their products to high performance, such as Weiand, Lenco, Hooker, Crane, and Amalie, and assisted with testing and development. Through those collaborations, his knowledge of the capabilities of the big-block Chevrolet compounded rapidly.

WJ had a background in product development that reached back into the 1960s, when he worked on the first successful tunnel ram manifold for a 427 of the time. His work with the rat engine design provided credibility that would open doors down the road and serve well in helping to cement his position as “the Professor.”

The rumblings in the early 1970s on the AHRA circuit were that WJ had the fastest big-block Camaro in the country. In 1974, he had a big-block Vega built for match racing and continued to steadily build his case, as he would throughout his career, in almost any car he drove.

WJ claimed top speed on the circuit at six races in 1974, running just one engine the entire season and recording a best time of 8.73 at 159 mph. He made an abundance of runs that year, and the following season, performance picked up even more. In Tulsa, WJ was No. 3 behind the more experienced racers Bill Jenkins and Larry Huff.

THE 1976 BULLET

WJ’s 1974 Camaro was powered by a 427 Chevrolet with a special crankshaft that reduced displacement to 397 ci. WJ would leave the starting line at approximately 8,000 rpm and use 9,600-rpm shift points.

At the 1976 AHRA Springnationals, he was in his Camaro and raced to low ET, just missing top speed of the meet on an 8.830 with a 153-mph pass that was 0.04 second off the world record. It was the fastest run ever for a fully legal big-block Chevy. He fell in the final to Ford pilot “Dyno” Don Nicholson.

Then at the next race, WJ knocked out the Gapp & Roush Ford in the first round before he was ousted by Bill Jenkins and his Vega in the final. The already-fast Camaro was picking up speed — and notoriety.

The 1976 AHRA race at Tulsa’s Okie Nationals stoked a rivalry between WJ and defending series champion Ken Dondero, who was piloting Jenkins’s Chevy Monza. This was one of two cars owned by Jenkins that raced in NHRA competition as well; Larry Lombardo raced the other.

WJ challenged Dondero to a one-round grudge race on Saturday night and lost by a handful of inches. Then on Sunday, the two were paired in the final round with grandstands packed. Johnson left first and never looked back, crossing the finish line with an 8.80 at 155.17 mph to his opponent’s 8.87 at 154.70 mph.

Dondero locked down the AHRA championship that season, but WJ made him work for it. WJ would claim an IHRA crown for himself in 1981 with Jerome Bradford. WJ was contending for the NHRA championship in 1976 while also chasing AHRA trophies and match racing.

The man who came to be known as “the Professor” finished second in the world in the NHRA. At the time, NHRA Pro Stock ran division races, known as the World Championship Series (WCS), as well as national events. Racers could claim events within their division, but they could also travel to other divisions in an attempt to block their adversaries from going rounds. WJ was counting points early, and by midseason he was strategizing to make appearances in Jenkins’s neck of the woods to try and gain a little leverage.

Heading into the NHRA Finals, WJ was facing a 596 points deficit and knew the championship would take everything he had and then some. It was possible, but WJ would have to win the race, pray that Jenkins’s driver Lombardo bowed out early, and break his own national record. The location of the event (Ontario Motor Speedway) was not prone to ideal conditions for Pro Stock records. The track had good “bite,” but the air wasn’t generally quite that favorable.

There was no record set, and Lombardo defeated WJ via a holeshot en route to the final round. When it was all said and done, WJ had put together a remarkable inaugural full-time season. It was not lost on a single soul that he was there to win, and a second-place finish for the year was disappointing, but it was also evidence of what the future would hold.

OLDSMOBILE STAKES CLAIM IN PRO STOCK

In 1979, the Oldsmobile representative involved in its motorsports program, Dale Smith, approached WJ at the Popular Hot Rodding meet in Martin, Michigan. Smith asked if WJ would be interested in running an Oldsmobile, and WJ replied, “Tell me what you’ve got and what kind of program you’re trying to put together, and we’ll talk.”

The conversation at the facility now known as US 131 Motorsports Park was the beginning of one of the longest and most notable partnerships in the history of drag racing. The first few years of WJ’s involvement with Olds were with a small-block he ran in the Starfire. He later outfitted the car with a big-block for NHRA Pro Stock competition.

In the early days, there was no cash involved in WJ’s partnership with Oldsmobile, only the provision of parts. “But because I was successful with that small-block Oldsmobile—it was one of the very first cars to run 160 mph—they took note,” stated WJ.

WHEELS WAY UP (sidebar)

Warren Johnson has always raced to win, but he also relished the opportunity to put into practice the research, development, and ideas he had away from the track. WJ viewed the Pro Stock meet at Minnesota Dragways in July 1971 as an opportunity to really dig into a few ideas he had been wanting to test—in particular, the usefulness of wheelie bars. The stunning results, captured by Minneapolis Star photographer Arthur Hager, definitively answered WJ’s query while putting on a spectacular show for everyone in attendance.

“We thought if the wheelie bars were employed inefficiently, they probably hurt performance,” said WJ. “We were playing with different styles: some axle-mounted, some chassis-mounted. As we went along, we figured that the other option was no wheelie bars at all.”

So, the Professor removed the accessories in question and headed up to the lanes for the semifinals of an exhibition race that had kicked off with 16 Pro Stockers on the property. He was the fastest on the block that day, but his drive to win didn’t do anything to squelch his deep drive to learn. As he launched, the wheels came up incredibly fast, and the rear bumper made contact with the ground, tires spinning through the entire ordeal. Despite a windshield full of sky, WJ had the knowledge and wherewithal to shift gears to keep the horsepower high and hopefully lessen the impact when the front tires finally came back down to earth. The jolt was still enough to flatten the headers and the oil pan, bend the frame, and crack some of the fiberglass along the front of the Camaro’s body.

“I was just trying to figure out how I was going to land the thing with a minimal amount of damage,” said WJ. “It really wasn’t too bad. It came down pretty straight, so it was a matter of coasting to the end of the track and bringing it back. Wheelie bars are required now, so the only option is to make them efficient. We eliminated one of the three options that day.”

After the event, WJ diagnosed that he had about 54 percent of the weight on the rear tires, and it should have been approximately 52 percent. Then 27 years of age, WJ went on to tell journalist Bob Schranck of the Minneapolis Star, “I don’t particularly like driving, just the idea of getting it to work well. But I haven’t found a driver I really trust.”