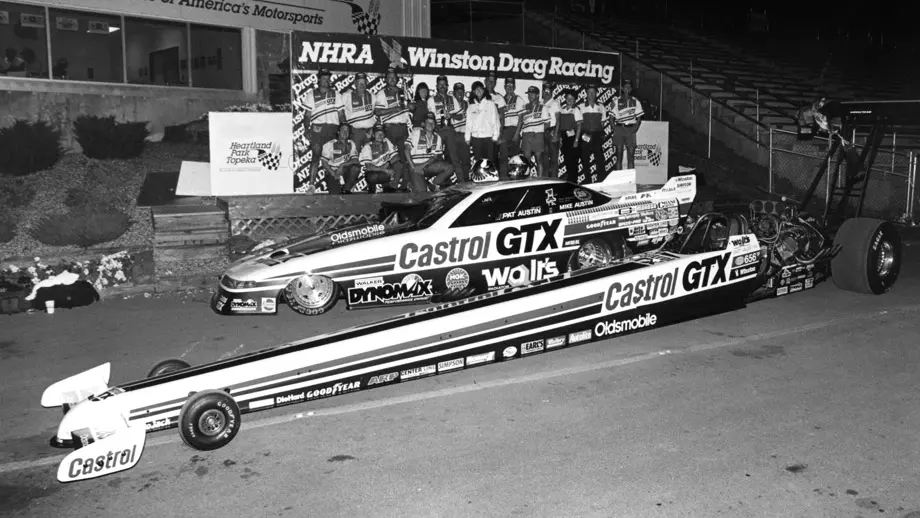

Pat Austin and "The Double"

The NHRA Mello Yello Drag Racing Series tour heads next week to Heartland Park Topeka, which has been the site of a lot of drag racing history over the last four decades, including the first four-second and 300-mph Funny Car passes way back in 1993 and, just last year Matt Hagan’s jaw-dropping 335-mph Funny Car pass, still the fastest in history.

The NHRA Mello Yello Drag Racing Series tour heads next week to Heartland Park Topeka, which has been the site of a lot of drag racing history over the last four decades, including the first four-second and 300-mph Funny Car passes way back in 1993 and, just last year Matt Hagan’s jaw-dropping 335-mph Funny Car pass, still the fastest in history.

But the Topeka track is also well known as the host of the first ever national event “double” -- one racer winning in two classes at the same race – when Pat Austin won in both Top Fuel and Alcohol Funny Car in 1991. Doubles have become increasingly more prevalent – we’ve already had two this year, and 35 in NHRA history – but when Austin pulled off the feat it was not only unprecedented but unbelievable – and all these years later it’s still pretty unbelievable.

From a purely personal standpoint, what Austin accomplished – and the backstory behind it – remains one of the highlights of my 35 years here at NHRA, which is really saying something. I’ve seen some amazing feats, incredible performances, white-knuckle suspense, and dizzying drama in those years, but I won’t ever forget the circumstances surrounding the magic of the fall of 1991.

Allow me to significantly backtrack to set the stage.

![]()

I first met Pat Austin, his father Walt, and brother Mike at Beech Bend Raceway Park in May of 1985. NHRA had just returned the SPORTSnationals to its roots at the charming Bowling Green, Ky., facility. Pat was just 20 then, about four years younger than me, and I interviewed him for a feature we were working on about young lions in the sport. We hit it off immediately and spent the next 15-plus years talking regularly on the phone as he piled up national event win after national event win. Alcohol Funny Car was my “beat” back then, and while I can’t say that I interviewed him after all 70 of his wins in the class – plus the five he won in Top Fuel – it’s safe to say that I did the majority of them.

I first met Pat Austin, his father Walt, and brother Mike at Beech Bend Raceway Park in May of 1985. NHRA had just returned the SPORTSnationals to its roots at the charming Bowling Green, Ky., facility. Pat was just 20 then, about four years younger than me, and I interviewed him for a feature we were working on about young lions in the sport. We hit it off immediately and spent the next 15-plus years talking regularly on the phone as he piled up national event win after national event win. Alcohol Funny Car was my “beat” back then, and while I can’t say that I interviewed him after all 70 of his wins in the class – plus the five he won in Top Fuel – it’s safe to say that I did the majority of them.

Austin impressed us all immediately. That SPORTSnationals marked his national event debut, and he opened by defeating Ken Veney and Lou Gasparrelli – two guys who had been part of the class since its inception more than a decade earlier – and finished in the top 10 that year.

The first of Austin’s 75 career wins came about a year after I met him, at the ’86 Cajun Nationals, and, ironically, sort of came at my expense. I had also befriended Division 4 Alcohol Funny Car racer Dal Denton earlier that year, and went on a brief tour with he and his team for a story for National Dragster, the culmination of which came at the Cajuns. I remember sweating over Denton’s sizzling Donovan powerplant between rounds in the unbelievable heat and humidity that made that such a notorious event, the sweat drops sizzling as they fell onto the valve covers while I whipped out the plugs. Austin, whose crew at the time included a very young Rob Flynn, won that event, beating “us” in the final, and never looked back.

By the start of the 1991 season, Austin – whom we at Dragster had quickly nicknamed “Pat Awesome” -- had already accumulated 34 victories (including three at Indy) and three season championships, but no one could have imagined what lay just ahead.

![]()

In seven short years since his return to fulltime Top Fuel competition in 1983, Gary Ormsby, who first began racing fuel dragsters in the early 1960s, had made an incredible impression on the class. From 1984 through the end of 1990, he’d collected 14 victories and the 1989 season championship with a crew led by Lee Beard that also included another young wrench on the rise, Mike Green. Ormsby was teammates on the Castrol GTX “superteam” with John Force (Funny Car), Larry Morgan (Pro Stock), Bill Barney (Alcohol Dragster), David Nickens (Comp), Rob Slaviniski (Super Gas), and, yes, Pat Austin.

In seven short years since his return to fulltime Top Fuel competition in 1983, Gary Ormsby, who first began racing fuel dragsters in the early 1960s, had made an incredible impression on the class. From 1984 through the end of 1990, he’d collected 14 victories and the 1989 season championship with a crew led by Lee Beard that also included another young wrench on the rise, Mike Green. Ormsby was teammates on the Castrol GTX “superteam” with John Force (Funny Car), Larry Morgan (Pro Stock), Bill Barney (Alcohol Dragster), David Nickens (Comp), Rob Slaviniski (Super Gas), and, yes, Pat Austin.

What few knew was that Ormsby had been diagnosed with cancer in mid-1989, and won the championship carrying that heavy burden on his shoulders even as he fought the dreaded disease. His last NHRA national event was in May 1991, at the Mid-South Nationals in Memphis, where he went to the semifinals before falling to Don Prudhomme.

He competed for the last time at a match race in late May at Heartland Park Topeka, where he defeated Lori Johns in three straight rounds. He missed the next couple of events, in Columbus, Montreal, and Englishtown, due to what was described publicly as an intestinal infection. (Little known fact: Don Garlits was offered the chance to drive for Ormsby in Englishtown, but Castrol GTX was a direct competitor to Garlits’ longtime benefactor, Kendall, so the plan was scotched.)

On July 16, just two weeks before the national event trail visited his Northern California neighborhood for the California Nationals in Sonoma, Ormsby checked into the University of California-Davis Medical Center where it was revealed that he had a malignant cancerous tumor in his lower abdomen and he began radiation treatments. Gordie Bonin took the wheel of the Castrol Top Fueler in Seattle, and Beard impressively tuned him to a couple of four-second runs and a semifinal finish.

Ormsby died at noon, Aug. 28, at his hometown Roseville Community Hospital, but not before setting in motion Austin's historical moment by selling his Top Fuel operation to Walt Austin.

![]()

Austin licensed quickly – and impressively – in the car in Seattle, running a competitive 5.08, and also killed the reaction timers. Few of us were surprised.

Austin licensed quickly – and impressively – in the car in Seattle, running a competitive 5.08, and also killed the reaction timers. Few of us were surprised.

The team – which also included yet another young crewmember on the rise, Dickie Venables -- made its debut on NHRA’s biggest stage, the U.S. Nationals. Austin vowed to make Ormsby proud, even in the face of unrealistic expectations. "Pressure," Austin told me that weekend, "is what makes you good. You have to rise to the occasion." Boy, did he.

He qualified No. 6 with a 5.05, then beat three of the sport's more experienced drivers -- Jimmy Nix, Eddie Hill, and Tom McEwen – with a pair of 5.0s and a 4.97, and otherworldly reaction times of .439, .415, and .419 to enter the final round of the U.S. Nationals in his debut performance.

Austin beat Tony Bartone to win the event's Alcohol Funny Car title, then turned his attention back to Top Fuel.

Waiting in the final was Kenny Bernstein, whose Budweiser King dragster had been mired in the 5.0s and had not responded to crew chief Dale Armstrong’s mechanical ministrations. The four-time Funny Car champ drove his Texas tail off just to reach the final, but was undoubtedly the underdog against Austin.

Austin fired first and burned out, but his inexperience cost him. The tires hooked early on the burnout, he tried to pedal it, the motor bogged, the engine went lean, and the blower backfired. Bernstein had won Indy again before he’d even fired the engine. To add salt to the wound, Bernstein smoked the tires on his final-round solo.

The photo below says it all, with Austin clutching his head in anguish (that's Venables walking ahead of him) as Bernstein backs up from his burnout.

I raced back to the Austin pit area, to a shocked and downtrodden crew, and described the scene this way for my article for National Dragster.

Crewman Dickie Venables remained in the cockpit of the Castrol GTX Special, staring straight ahead. Dana Kimmel sat glumly on a table in the quiet pit area, idly swinging his legs and looking at the still-tethered race car. Brian Smith fished a cold beer out of the cooler. Crew chief Lee Beard was in hushed conference with Walt Austin.

And Pat Austin, whose impossible dream of scoring an unprecedented double -- winning Indy in his Top Fuel debut and backing up his Alcohol Funny Car win of just minutes earlier -- had died with a heartbreaking blower backfire on the burnout of a final round that he undoubtedly would have won, seemed on the verge of tears.

The 26-year-old driving sensation, whose fourth straight U.S. Nationals Alcohol Funny Car title, the 41st National event win of his six-year career, had moved him into a tie for second on the career win list with quarter-mile legend Don Prudhomme, couldn't even bring himself to talk to Team Castrol patriarch John Gardella, who has been like a second father to him. He just sat on the tailgate of the tow vehicle, his chin in his hand and a faraway look in his eyes, dreaming of what might have been.

What might have been -- and what very possibly still is -- the greatest driving performance in drag-racing history ended one round short of immortality, and no one felt more to blame than Austin.

After the obligatory meeting with the media in the pressroom – where Austin took 100 percent of the blame – and a half-hearted celebration in the Alcohol Funny Car winner's circle, Austin trudged back to his pit area with me. It was there, walking through the darkened pits, that us two old pals who had come up through the sport through different paths and roles in the previous six years, chatted quietly. "I believe that everything happens for a reason," he said. "I just don't know what the reason is for us losing."

He was still mad at himself, still raw with emotion, and told me, ‘"I guarantee that I will not only win with the Top Fueler before the season is over, but I'll win with both cars at the same race."

I printed that quote as part of my coverage, much to Austin’s dismay. He had said and surely meant the words, but apparently meant them to stay just between us lest his new peers find him too cocky. I’d never printed an “off the record” quote in my life, so I, too, was aghast. At least for 27 days.

![]()

After a down-to-earth first-round exit at the next event, the Keystone Nationals in Pennsylvania, Austin and team rolled into Heartland Park Topeka for the NHRA Heartland Nationals, and any early indication that history was in the making was far from present.

After a down-to-earth first-round exit at the next event, the Keystone Nationals in Pennsylvania, Austin and team rolled into Heartland Park Topeka for the NHRA Heartland Nationals, and any early indication that history was in the making was far from present.

After three of four qualifying sessions, Austin wasn’t even in the show. It took a last-ditch 5.02 to crack what was then the quickest field in class history (5.095 bump). Austin then took out a tire-smoking Tommy Johnson Jr. in round one and Maurice DuPont in the Hammertime entry with back-to-back 5.02s, then – for the second time in three races -- beat veteran McEwen in the semifinals on a holeshot.

After dispatching Chuck Cheeseman in the Alcohol Funny Car final, Austin saddled up for another shot at history. Three-time Top Fuel champ Joe Amato – who was on his way to his fourth crown – was the heavy favorite over Austin in the Top Fuel final after a series of four-second passes, but Austin and Beard were ready for him. Austin cut a spectacular .407 light (to Amato's .464) then ran his first four, a 4.97, to beat Amato’s 5.01, and triumphantly parked both cars in the HPT winner's circle.

Austin’s dual wins not only made him the first driver to win two eliminator titles at the same race but also gave 10 victories on the season, an NHRA single-season record. Austin would add a second Top Fuel win at the World Finals that year, avenging his Indy loss by beating Bernstein in the final.

Just to prove it was no fluke, he repeated that Topeka feat at the notorious 1992 Phoenix event. It wasn't until later that year, at the '92 Atlanta event, that Edmond Richardson scored the first non-Austin double. Austin remains the only driver to double in a Pro and Sportsman category though several others -- most recently Jeg Coughlin Jr. and Erica Enders -- have tried.

Just to prove it was no fluke, he repeated that Topeka feat at the notorious 1992 Phoenix event. It wasn't until later that year, at the '92 Atlanta event, that Edmond Richardson scored the first non-Austin double. Austin remains the only driver to double in a Pro and Sportsman category though several others -- most recently Jeg Coughlin Jr. and Erica Enders -- have tried.

Austin tallied five Top Fuel wins and 70 Alcohol Funny Car Wallys to finish with a tidy 75 victories before retiring, cementing his place as one of NHRA’s all-time great drivers. He was voted No. 13 on NHRA’s list of Top 50 Racers in 2000.

![]()

It’s been a long time since Pat and I had talked, but one phone call Thursday fixed that, and we spent a great time on the phone catching up, comparing families and middle-aged life.

It’s been a long time since Pat and I had talked, but one phone call Thursday fixed that, and we spent a great time on the phone catching up, comparing families and middle-aged life.

Of course, I wanted to hear his memories, 26 years down the road from that amazing accomplishment.

“Man, it seems like it was yesterday,” he said. “When I go by my dad’s shop, we have pictures on the wall and I see a lot of happy people, good times, and great memories.

“I think back about that whole Indy thing, the debut, and the blower explosion in the final, and it was like catching a great big fish that you get to the boat and the line breaks, and you just wonder if you’re ever going to get another one.

“I was confident, but mad more than anything, when I told you that we will win. When we got to Topeka and got the car running good, I was even more confident. When we won in the alcohol car, I don’t know if I was ever more determined to win a race.”

Facing world champ Amato in the Topeka final was a huge motivation for Austin, one that went far beyond the Castrol vs. Valvoline sponsor battle.

“I had never raced Joe in eliminations, but I knew how intense the Amato-Ormsby rivalry had been, and I wanted to be able to carry that on for Gary and his guys and, of course, for the people at Castrol,” he said. “I knew that if we won that final, it would make the Indy loss not sting as bad. Once I got past the burnout, I was laser focused.”

But, really, Pat? A .407 light?

“Before a run, I used to close my eyes and visualize the yellow on the Christmas Tree. When I could do that – and I could do that the majority of the time at that period of my career – I was deadly on the line. I didn’t even have to do that for that final against Amato. I knew what I was going to do, and just hoped we didn’t smoke the tires or get out of shape.

“Obviously, Joe was at the top of his game, and if you can’t get pumped up to race someone like him, with a second chance at a double, you’re in the wrong profession.”

Austin kept on winning for another decade, but hit the wall in 2002. His last win was at the Winternationals that year – ironically, beating his uncle, Bucky, in the final – but the famous fire that he had stoked so long was diminishing after nearly 20 years of hard racing.

“It was a lot of things, really,” he said. “We were struggling a little with the fuel car and had been through a lot of crew changes. I learned how to run a nitro car from guys like Lee Beard, Dana Kimmel, Tim Richards, Jim Brissette, Dan Olson, Frank Bradley; I really paid attention to what they were doing so when we went out on our own, we made good power but I was messed up in the clutch department. I was pretty headstrong trying to do it my way, but if I could do it again, I’d do it differently.

“It was a lot of things, really,” he said. “We were struggling a little with the fuel car and had been through a lot of crew changes. I learned how to run a nitro car from guys like Lee Beard, Dana Kimmel, Tim Richards, Jim Brissette, Dan Olson, Frank Bradley; I really paid attention to what they were doing so when we went out on our own, we made good power but I was messed up in the clutch department. I was pretty headstrong trying to do it my way, but if I could do it again, I’d do it differently.

“I think everyone on the team just got burned out. The wins didn’t mean as much and the losing hurt more than ever. I had lost the fire in my belly; I just didn’t have the fight in me anymore. I thought I wanted to race, thought I loved to race, I thought I needed to race, but I was just hanging in there to be able to race with my family.

“Plus I had started a family of my own and was missing time with my wife [Keila] and kids [Drew and Allison]. After we stopped racing, I went to wrestling four nights a week with Drew and tournaments every weekend for 10 years, and did the same thing with football and baseball. I put the same energy into that that I put into racing, and I wouldn’t change that for the world.”

Anyone who has paid attention to nostalgia drag racing lately (and that’s probably the majority of our Insider Nation) knows that the Austins are once again racing, with Pat’s son, 23-year-old Drew, wheeling an A/Fuel Dragster, and doing it quite successfully.

Anyone who has paid attention to nostalgia drag racing lately (and that’s probably the majority of our Insider Nation) knows that the Austins are once again racing, with Pat’s son, 23-year-old Drew, wheeling an A/Fuel Dragster, and doing it quite successfully.

“It’s just a lot of fun without all of the pressure of the big show,” Pat said. “My wife, my daughter, my dad, and my brother are there on the starting line every race, so it’s kind of like going back in time for me. And Drew is doing a good job.”

With a dad like Pat Austin, how could he not? Surely there’s some genetics involved there, right Pat?

“It’s funny, because when we started Drew asked me, ‘What do I need to do to become a good driver?’ and I just told him, ‘I can’t help you. You either have it or you don’t. Go drive the car.’ Of course, there are tips I do share with him about not driving over his head or about staging strategies, but mostly I let him do what he thinks, and he’s doing a great job.

“And watching my kid race, that gives me back that old fire. It’s a good feeling.”