'King Richard': Damndest Thing You Ever Saw

|

Frankly, I don’t even know where to begin when writing on The Life and Times of Richard Tharp. It has been an article I’ve wanted to write for years but put off for the same reasons I’m facing now staring at a mostly blank computer screen with less than 50 words of hemming and hawing.

How do you adequately and colorfully describe a life lived more fully (and wildly) than most and a career filled with wins, championships, and unforgettable moments? How do you begin to tell the tale of a Rebel With No Cause other than a good time and a good e.t., and do it for a PG audience? After all, this is a womanzing wheelman who used to hand out business cards emblazoned with the saying “Texas & Tharp: The Damndest Thing You Ever Saw!" and a guy whose dragster’s rear wing bore the mantra “A star I are, a saint I ain’t.”

And when I mentioned to several people that I was working on this story, I could almost hear them gleefully rubbing their hands together in anticipation of Texas-sized titillating tales of the road. I mean, no pressure, right?

Although being able to begin such a tale of dragdom and debauchery is why they pay me “the big bucks,” I’m going to defer for a second to another Texas denizen who probably knows Tharp as well as the man himself, longtime Lone Star scribe Dave Densmore, who before beginning his long stint as John Force’s keeper, palled around with Texas legends like “King Richard” for years. Densmore was part of my Top 50 Drivers panel in 2001, and when Tharp made the list at No. 49, I asked Dens to write his article, which began thusly:

“In the 1960s and '70s, an era which produced some of drag racing's most colorful characters, none was more colorful than Richard Tharp. … So outrageous and memorable were Tharp's off-track antics that people tend to forget that he was one of the finest pure drivers in the sport's history.”

I read those sentences to Tharp Tuesday and asked how they suited him.

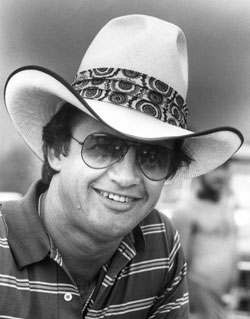

Of the scores of candid Richard Tharp photos in our library, I'd guess that well more than 75 percent of them feature him wearing a cowboy hat of some sort. He's as Texas as they come.

|

“I feel like that’s a fair assessment,” he agreed. “A lot of people remember the off-track stuff, but if you talk to the other drivers and the car owners I drove for, like Paul Candies, the Carroll brothers, and [Bob] Creitz, I think they all respected what I did on the track.”

Tharp then good-naturedly went on to talk about his famously heavy right foot and how he loved to drive a car “out the back door,” beyond the old speed trap that used to extend 66 feet past the finish line. Not only did Tharp routinely drive a car “out the back door,” but typically across the backyard, through the alley, and into the neighbor’s backyard.

“I just loved going fast,” he attested. “When Kenny Bernstein ran 300 mph, Candies would tell people, ‘Tharp was the first to run 300, but it was 200 feet past the lights.’ Densmore also wrote about me, ‘He’s one of the best there is at driving a car out of trouble, but he’s also the best there is at driving one into trouble.’ "

Tharp, like Bernstein, came up to the superstar ranks through the tough Texas-based Pro Fuel Circuit of Top Fuel cars in the 1960s.

Tharp came out of Las Cruces, N.M., driving for a guy named George Brazil but soon transplanted to Dallas, where he wheeled dragsters for Raymond Austin (Neal-Austin-Tharp), Mike Brown (Assassin), James Bush and J.L.Payne (Bush & Payne), and the famed “Texas Whips,” the Carroll brothers, "Bones" and Curt.

Densmore also wrote of Tharp, “Once, when another Dallas driver was having difficulty getting his dragster down the racetrack because of a perceived chassis problem, Tharp was asked to make a checkout run. After posting a time only a tenth off the track record, Tharp unbuckled, climbed out of the car, and in his drawl said, ‘Nothing wrong with the car. I think it's the driver.’ "

Tharp drove for the Carroll brothers -- "Bones" and Curt -- on numerous occasions, in both front- and rear-engine cars.

|

Tharp’s stint with the Carrolls was cut short by Uncle Sam in 1966, when Tharp’s name came up in the Vietnam draft, but Tharp didn’t go easily. In what has become perhaps the best-known Tharp tale, he was on the lam from the authorities for failing to report and was ultimately found hiding in the closet of good pal Jimmy Nix. I’ve heard just the classic ending of this story dozens of times from dozens of people, but Tharp wanted to give me the whole story.

“I was draft-dodging but still racing,” he began spinning his tale, already laughing at the memory. “The FBI had been coming by my mother’s house and threatening to put me in Leavenworth and everything. We were at Tulsa [Okla.] for the 1966 World Finals, and we’d won the first round, and these two guys come walking up in these suits, and they said, ‘Are you Richard Tharp?’ And I said, ‘No, I’m not,’ but they pulled out this picture and said, ‘Well, you sure look exactly like him …’ I just started laughing.

“They were pretty good guys, and they said they would let me finish racing, but then I had to go with them. Nix had gotten beat in the first round, and we got beat in the second round. As I pulled off at the other end of the track, I see Nix’s truck and trailer coming by loaded up for home, so I just jumped into his truck and left with him out the gate.”

The whole time that Tharp is telling me this story, he’s punctuating almost every sentence with laughter. He's enjoying telling it as much as I am listening.

“The next day, Nix’s mother called and told him that the FBI knew he was harboring me, and about that time, there was a knock on the door. All those old houses had a little-bitty closet right by the front door to hang your coat and your cap. So Nix told me, ‘Jump in there; I’ll tell them you’re not here.’ So I jumped in there, and I could see them through the crack in the door and could hear everything. One of them unbuttoned his coat so Jimmy could see his gun and said, ‘Listen, we know he’s here, and we don’t want to hurt anybody, and nobody else needs to go to jail, but we’re going to take Richard with us, or you’re going to go with us for harboring a fugitive. Now where’s he at?’

“And Nix says, ‘He’s right there in that closet.’ Man, that’s a funny story,” he concluded, still cracking up. The story goes on that when he was handcuffed, Tharp was wearing one of Nix’s racing jackets, and “the Smilin’ Okie” reportedly asked that the G-men unshackle him so he could get his coat back.

Tharp was packed off to join the Army, and while the majority of his basic-training unit went off to truck-driving and mechanic school, Tharp was tagged for infantry training. He actually turned out to be a good soldier, graduating from both paratrooper training and a dog-handling class, and served courageously in Vietnam as a "lurp" (LRRP, long-range reconnaissance patrol) for more than a year and even extended his tour by four months to ensure that once he got home he would be discharged from the Army and able to get back to racing.

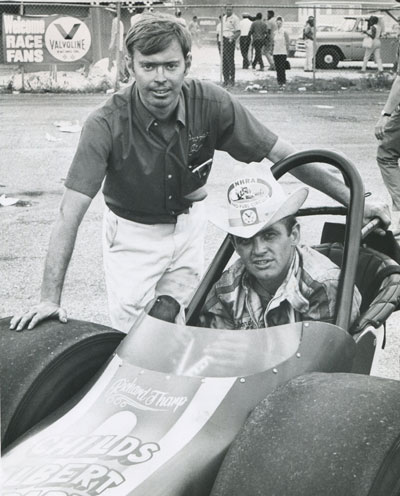

Tharp, in his ever-present cowboy hat, with Jim Albert

|

When he returned Stateside in late 1968, he drove for Rocky Childs and Jim Albert, of Childs & Albert fame, leading to another great Tharp moment, as related by Densmore.

“Traveling with Jimmy Albert, Tharp was late arriving in Oklahoma City for one Texas Pro Fuel Circuit race. It had rained the previous three days, and track officials had employed a helicopter to assist with the dry-out process. All the helicopter really had done, though, was dry out a quarter-inch of topsoil -- which is why all the early arrivals were parked on asphalt, on the track's road course. All of this was unknown to Tharp, who, late as usual, came flying into the track at the wheel of the team's crew-cab truck, Albert in the passenger's seat. Seeing all the open area, Tharp drove the rig into a clearing -- and promptly sank it up to the axles in a couple feet of mud. Undaunted, Tharp enlisted help in building a plywood ‘bridge’ to get the race car from the trailer to the nearest asphalt and then to the staging lanes. He qualified on one shot and ultimately went to the final round, but it was another in a long list of experiences that left Albert shell-shocked.”

After Albert decided to curtail his racing activities in mid-1969, Tharp went back to driving for the Carrolls and won the Division 4 championship, then hopped behind the wheel of the car run by Creitz and Ed Donovan in 1970 and became the guy in the other lane in the final at Lions Drag Strip in March when Don Garlits blew half his right foot off in one of the most legendary incidents in drag racing history.

I made the mistake of asking Tharp, “You red-lighted in that race, right?” having read many times Garlits’ side of the story, how Garlits should have won the race because Tharp had red-lighted but that the shrapnel from Garlits’ transmission explosion short-circuited the timing system and turned off Tharp’s red-light.

“No, no, no,” he stops me. “If I had red-lighted, we never would have gotten the money. Garlits tells everyone I red-lighted, and it used to drive Creitz and Donovan crazy. That’s just one of Garlits’ deals. We got the money, we got the points, and that’s the truth. But that whole Grand American tour was a lot of fun. We went all over and had a lot of fun with guys like [Jim] Nicoll and Don Cook and ‘Snake’ and ‘Goose’ and everyone. That was one of the best tours I ever went on, and me and Creitz had a lot of fun. He was quite the prankster. There was a lot of fireworks involved.”

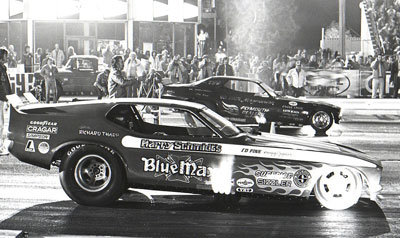

Like a lot of Top Fuel drivers, Tharp saw the handwriting on the wall that Funny Cars were becoming the new kings of match race bookings and took over the saddle of Harry Schmidt’s famed Blue Max Mustang when Jake Johnston left to drive for Gene Snow in 1971.

|

|

“I liked dragsters and Funny Cars both, but I really liked the burnouts and the dry hops in the Funny Cars, and Harry was amazing to work with,” said Tharp. “He was so smart and inventive. His [1970] Don Hardy car was the first with a dragster roll cage on it. His cars were always light, and he had the first quick-change rear end in the class. We won a lot with that car; I won two of the first three races in the car. The ’72 car was my favorite. We booked 118 dates one year with that car and probably won 85 percent of our races. That car was just a genuine badass.”

One Fourth of July week, they ran seven straight days: Napierville, Ont., on Tuesday; Toronto on Wednesday; Detroit on Thursday; Union Grove, Wis., on Friday; Martin, Mich., on Saturday; Rockford, Ill., on Sunday in the day; Humboldt, Iowa, Sunday night, and Sioux Falls, Iowa, on Monday.

“Other times, we’d run in Miami on Sunday night and Orange County [Calif.] on Wednesday night,” he remembered. “It’d take a day to get from Miami to Texas, then a day to get across Texas, and a day to get on to L.A. That was some hard driving in an old ramp truck, but back then, we didn’t think much of it.”

Tharp drove for Schmidt through 1973, then drove partial seasons for fellow Texan “Big Mike” Burkart – winning five times on the IHRA tour -- and for Don Schumacher in the aerodynamic Wonder Wagon Vega in 1974, and he also drove briefly for Larry Huff in the equally sleek Soapy Sales Dart.

|

Tharp returned to his dragster roots in 1975, reuniting with the Carroll brothers, a decision that serendipitously led to his championship-winning tenure with the Candies & Hughes team. When the Carroll car ran 5.97 at the 1975 Summernationals – the first sub-six-second pass at Raceway Park – to qualify No. 1, that performance caught the eye of Candies, the walletman for the one of the sport’s premier teams, who was looking for a driver to replace Dave Settles, who had decided to build an A/Fuel Dragster for himself.

“We raced against Leonard [Hughes] and Paul a lot when they were running Funny Cars, so they knew who I was. Curt called me and told me that Paul wanted to hire me for 1976 and gave me his blessing; he told me [Candies] was crazy if he didn’t hire me. A few days later, Paul called me, and I was hired, but Curt and I remained good friends.”

Their first season together couldn’t have gone better. They won the inaugural Cajun Nationals in Baton Rouge, La. (not a points-earning event at the time), then won the Summernationals, runner-upped at Le Grandnational, and won the big one, the U.S. Nationals, en route to the championship. They won the Cajun Nationals again the next year and would have won Indy again, according to Tharp, had Garlits not gone over to help Dennis Baca before the final, giving key engine and driveline components to the unheralded California racer prior to the final.

After losing their car in the crash in Seattle in 1979, Candies & Hughes and Tharp rented John Kimble's Southern California entry to run the World Finals and managed to hang on to their spot in the top 10 standings. In their six seasons together, they always finished in the top 10.

|

The only serious accident of Tharp’s career came in the employ of Candies & Hughes, during the second round at the 1979 Fallnationals. Tharp received a bye when Hank Johnson had to shut off his rail, but hard tire shake knocked out Tharp, and the blue charger went off the side of the Seattle track at full steam, throwing up rooster tails of dirt before impacting something and exploding into pieces. Surprisingly, other than a concussion, Tharp’s only injury came during the extrication process, and from an unlikely source.

“They couldn’t get my arm restraints unhooked, so [Seattle track owner Bill] Doner takes out his pocketknife and ends up sticking me through my firesuit; I needed four stitches in my arm! It’s a good thing I was knocked out when that happened.” (Former NHRA Top Fuel driver Carl Olson has a humorous story about this incident -- at the time, he was an NHRA official and among the first to arrive – that I’ll share next week.)

Cajun Nationals fans cheered for their home-state team, which won the event back to back, 1976-77.

|

In six NHRA seasons and 46 starts with the Candies & Hughes team, Tharp reached nine finals and five winner’s circles, qualified No. 1 seven times, always finished in the top 10, and compiled an impressive 82-46 win-loss record in the face of tough competition with Garlits, Shirley Muldowney, and Gary Beck.

Although the jovial Candies and Tharp got along well, Tharp’s after-hours antics didn’t often sit well with the sometimes cantankerous Hughes.

“Leonard was the reason we had so much success on the track, but he was so hard to get along with,” said Tharp. “We clashed big time. Paul and I always got along – still do – but Leonard didn’t like us going out and drinking at night. I figured as long as I was with Paul, that should be OK, right?”

“If you knew how to put up with Richard, he was OK,” Candies told me, “but Leonard didn’t drink and didn’t approve of anyone else drinking. Finally, I just couldn’t make him and Leonard get along anymore.”

(Candies also good-naturedly deferred from sharing any “Tharp stories” because most of what he had was “probably not publishable.”)

(Above) After leaving the Candies & Hughes team, Tharp raced midgets in 1982, then returned in 1983 with the pretty and fast Kilpatrick & Connell entry (below).

|

|

After finishing eighth in 1981, the team released Tharp and hired the more puritanical Mark Oswald, and Tharp found a new passion racing USAC midget and sprint cars. Behind the wheel, Tharp did well locally – he had equipped his car with a Top Fuel-like high-speed leanout button for quick passes, a tactic previously unheard-of in the class -- but turned over the cockpit to seasoned drivers such as Johnny Parsons Jr. and Ken Schrader at bigger midget events and even had famed Doug Wolfgang drive his sprint car.

Tharp returned to the quarter-mile in 1983 with a quality ride financed carte blanche by Mark Connell, owner of Rio Airways, in concert with Texas car dealer Mike Kilpatrick and tuner Bill Schultz. The Kilpatrick & Connell car won the IHRA championship and was a hard runner on the NHRA tour, winning the 1983 Springnationals and runner-upping at the Southern Nationals, and collected two more career low-qualifying efforts. The car was a constant threat to set low e.t. Tharp’s 5.447 at the IHRA meet in Milan, Mich., was the fifth-quickest pass of the 1983 season and the only pass to break up the stranglehold of Larry Minor’s two-car operation, which ran 17 of the year’s 18 quickest times.

The Kilpatrick & Connell operation lasted just one season, and Tharp sold the Swindahl-built car to Snow, who later sold it to Dan Pastorini, and that was the car in which the former NFL quarterback won his only Top Fuel title, at the 1986 Southern Nationals.

|

Tharp sat out of racing until an ill-advised and frustrating return to the sport in 1988, behind the wheel of a woefully unprepared resurrected Blue Max Funny Car for longtime pal Raymond Beadle.

“I never should have done that,” he lamented. “The car was way out of date, and everything was worn out, and Raymond was really concentrating more on his NASCAR team. Driving that car was the worst decision I ever made in drag racing.”

It certainly wasn’t the car in which he deserved to end his great driving career, and, honestly, the effort made such little impact that few people remember he even drove the car, which is just fine with Tharp.

As mentioned, Tharp was just as well-known for his antics at the local watering hole as in the water box. Dressed appropriately for any occasion with his trademark cowboy hat and boots, an evening on the town with “King Richard” was likely to yield a hot blonde, a hangover, or a black eye -- on a good night, all three. I asked him how he would describe himself.

“Pretty free-going, I guess,” said the lifelong bachelor after some contemplation. “It was just a different time than it is now. I wouldn’t trade one minute of it for anything, not one minute. We just had a real good time in everything we did. There were a lot of women and a lot of drinking. Someone asked me a while ago if I missed the races; I told them I didn’t miss the racing one bit, but I sure miss the women."

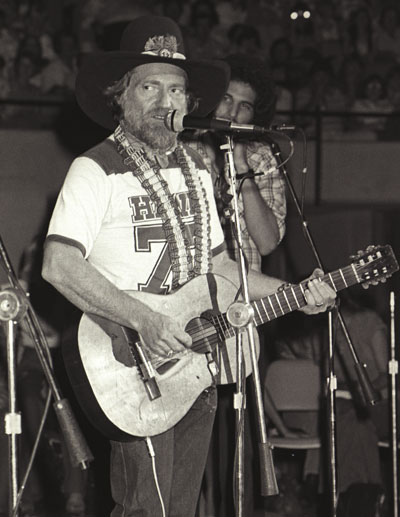

Country-western legend Willie Nelson was and remains a good friend of Tharp's. The Candies & Hughes team would routinely attend his concerts, including this one, held near the 1977 Cajun Nationals.

|

With all of his merry gallivanting, Tharp picked up a posse of pretty powerful party pals who enjoyed the nightlife as much as he did, including legendary country-western heroes Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings and Dallas Cowboys bad boy Thomas "Hollywood" Henderson, to name but a few.

“Just a bunch of good ol’ Texas boys,” he said of his famous friends. “Just hanging out around town, we’d run into them. Gary Busey, too. I’m still good friends with Willie; I don’t see him as much anymore, but we had us some good times. One of my favorite Willie stories is when he played the Hollywood Bowl and I introduced Linda [Vaughn] to him, and he sang ‘Georgia On My Mind’ for her. Linda was so thrilled that he sang the song looking at her, and I told him later about it, and he told me he wasn’t singing the song as much to her as to ‘them’ [referring to part of Vaughn’s famously well-endowed anatomy].

“One year, Willie was in concert in California about the same time as the World Finals, so everyone was coming to me for tickets, and I had like 38 people asking me for backstage passes. I had no idea how I was going to come through, but I went in there and said, ‘Willie, I need 38 backstage passes.’ He said, ‘What for?’ And I told him, ‘Well, I told all these people I’d get them in.’ He said, ‘Well, you go out there and tell them the truth: Tell them you lied.’ He’s really a funny guy, a great guy.”

“That was the great thing about hanging around with Richard,” added Candies. “You could always expect something different coming. If Willie was playing anywhere within 100 miles of a race, we’d go and get them backstage passes we needed … and other activities.”

(Tuesday's column will include more Tharp tales and other notes collected in the past few weeks.)

Although Tharp hasn’t driven for nearly 25 years – he passed up a few offers to drive cars that weren’t top-caliber – he’s still well-remembered in the community and is a regular at nostalgia affairs. His career was honored when he was inducted into the International Drag Racing Hall of Fame in 1999, the same year that Candies, Hughes, Creitz, and Snow were inducted.

It was at the induction ceremony that Tharp gave the speech he thinks best defined his career: “I was very lucky. I always had the best cars. I always had the best owners. I always had the best crew chiefs. I always did what I wanted to do. I always said what I wanted to say. I always argued with everybody else. And here I am, being inducted into the International Hall of Fame.

“It’s kind of a sign of defeat,” he deadpanned.

|

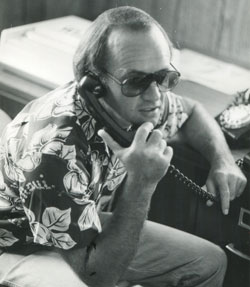

As noted earlier, Tharp was on the sidelines in 1982, which was my first year at National DRAGSTER, and I didn’t meet him until I took my first road trip on the job, to the 1983 Springnationals in Columbus, which he won in explosive fashion. He bombed the supercharger off his car on numerous runs and spent a good bit of time on the phone trying to track down more blowers, as can be seen in this photo snapped at the event by ND Photo Editor Leslie Lovett, after which Lovett introduced me to him.

(Tharp later explained to me that this was the result of a faulty hydrometer that was reading 11 percent more nitro than they had planned.)

Tharp’s presence on the national event scene after that was spotty, ending rather ingloriously with the less-than-competitive Blue Max v4.0. Throughout the years, and seemingly out of nowhere, the good-natured Texan took a liking to me and befriended me, sitting down in the media room with me at numerous events just to watch the racing and talk about the old days.

|

Recently hitting 70, Tharp is still slim and trim, just 20 pounds above his 152-pound driving weight, thanks to a regimen of running from auction to auction buying cars wholesale to feed the 750-car-a-month appetite of hungry car dealers. He lives in Carrolltown, just outside the Dallas city limits, sees Beadle two or three times a week, and still wears that cowboy hat and boots for pretty much every occasion. That's him at right last year when he and Beadle flew in from Texas to attend Don Prudhomme’s surprise 70th birthday party at the NHRA museum.

Tharp’s friendship and continuing communications – he was one of the first to let me know we’d lost former Blue Max owner Schmidt earlier this year – are what make my job amazing more than 30 years later. I’ve said it before and will say it until the day they kick me out the door (and probably even after that): For a teenage pit-rope track rat, there is no greater dream come true than to be befriended, appreciated, and respected by the legends whom you grew up watching.

Thanks to all of the heroes who allow me into their lives and into their memories. That’s when this column is at its best.