All the world was a colorful Circus when Bob Gerdes painted race cars

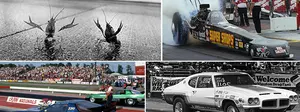

Although today's performances and packed fields might make an argument otherwise, for many (including most readers of this column, I’d surmise), the glory days of the Funny Car class were the early- to mid-1970s. It wasn't just the sheer number of cars that toured across the country to match races near and far, but the cars themselves. In the era before corporate sponsorships or even big sponsorships of any kind, the cars were painted to the owner’s whims, with colorful names and even more colorful paint schemes.

While the West Coast certainly seemed to be Ground Zero for the Funny Car craze, the East Coast certainly had more than its fair share of strong contenders and popular drivers. What the East Coast didn't seem to have, however, was a number of talented artists to apply the colorful schemes to these cars. While California had the likes of Bill Carter and Tom Stratton and the scores of cars that came out of Don Kirby's Funny Car factory, the main man on the East Coast was Bob Gerdes, who made his Circus Custom Paints business the center of the East Coast Funny Car universe beginning in the early 1970s.

We lost Gerdes on Jan. 2 at age 80 after a long series of medical issues finally silenced his airbrush, but he left behind a legacy of beautiful cars that is as indelible as the paint that covered them. The list of his clients is a Who’s Who of East Coast racers — think of any Funny Car racer from the region over the last four-plus decades and Gerdes was probably their guy. Gerdes also painted dragsters and door cars, but he was best known for his Funny Car work.

Raising the big top

Gerdes was born in New Jersey, where Circus was largely based over the years — although he did venture out to Upstate New York for a period — going from the original shop in Lyndhurst, N.J., to Hebron, N.Y., and then back to Farmingdale, N.J.

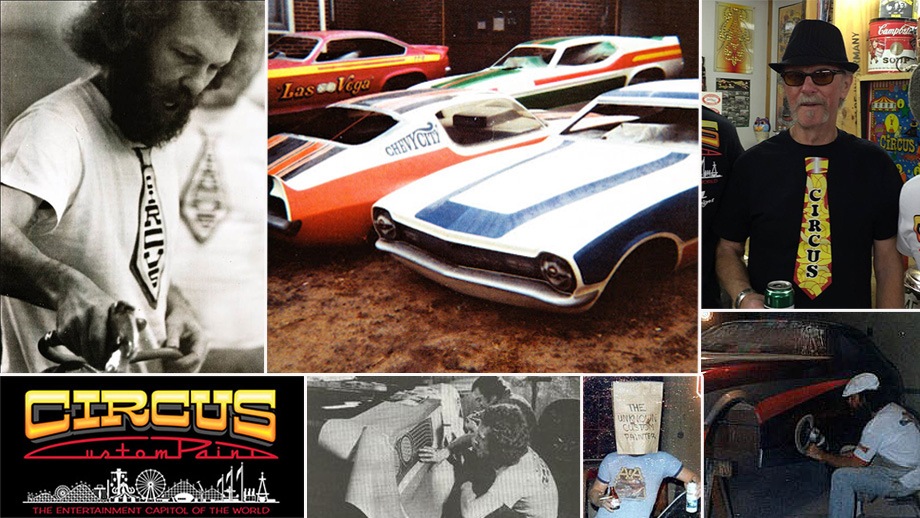

Before he founded Circus in 1971, Gerdes painted show cars before a fateful pairing with Julian “Mr. J” Braet when they collaborated to paint and letter Kenny Poffenberger’s Poff’s Super Puffer Corvair. The intricately detailed paint scheme caught the eye of his fellow racers, and before you knew it, the big tent was going up at Circus, and Gerdes and Braet became a dynamic duo: Gerdes laying down the colors and Braet doing the delicate airbrush work of pinstriping, lettering, and grille and head/taillight details.

From left, Bob Gerdes, Funny Car racer Les Cassidy, Cassidy's nephew, Jody; Don Pettigrew; and "Big Artie” Lajewski

In addition to applying original schemes, Gerdes added fiberglass fabricator Don Pettigrew (known humorously as “Don Divorce”) and “Big Artie” Lajewski (who at 6-foot-8 and 300 pounds also served as Circus’ "Sargent-At-Arms”) to become a full-service operation that could provide a respite for traveling teams to bring their damaged and road-weary cars in for a touch-up or some fresh ‘glass work.

A day in the life

Franklin Amiano, a past contributor to this column, went to work with Gerdes in 1973 on loan from the Cassidy Brothers team and had a front-row seat to the early heydays at Circus.

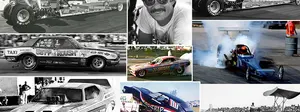

Scenes from the madhouse. That's Amiano top right with a "half-shaved" Gerdes

“It wasn't a job; it was an alternate lifestyle that I really needed after four years in the Air Force, including a tour of VietNam,” he said. “Often, Bob, Artie, and I would work all through the night to the sounds of Alison Steele, the Nightbird on WNEW-FM 102.7 out of New York City. There was always cold beer in the fridge and enough weed to roll a joint. Looking back, we turned out an amazing body of work from a shop that didn't even have a spray booth.

"We were often referred to as 'Commander Gerdes and his Lost Planet Airmen.' Richie Gerard was a biker who would come in to color sand and buff everything, and he did beautiful work. Finally, we had two world-class graphic artists who would do all the lettering, pinstriping, and airbrush work. First was Mr. J, Julian Braet, an excellent cartoonist who created the 'Jungle' image for 'Jungle Jim' Liberman, and, around 1975, Glen Weisgerber [Glen Designs] started doing some cars. We caught a window in time that will never happen again.

“For whatever reason, unlike in California, there weren’t a lot of people painting race cars on the East Coast,” he continued. “Guys would take their cars to a regular body shop or have a friend paint it, but they never looked like our cars. Later on in the ‘70s. Dickie Bell out of Massachusettes and Joe Siti out of Philadelphia came on the scene, but in those first days, it was all Gerdes.

“We were tucked away in the middle of a very Italian neighborhood in North Jersey. We would give people directions, and they would stop a block away and call and say, ‘This can't be right,’ and we’d tell them we’d go out on the street and wave them down.

“They’d come around the corner, and there's transporters parked on both sides of the street, no matter the time of year. Guys like Gene Snow and Kenny Bernstein, if their car got damaged on the road somewhere and they needed to get it fixed, they’d call Gerdes and somehow we'd get them in.”

Winter wonderland

Winter, of course, was the busiest time at Circus as teams would bring their cars in for paint before the season began, which, for many of them, was the NHRA Gatornationals in March, and this being New Jersey, it wasn't uncommon to have snow on the ground throughout all the winter months, and the line for work was sometimes long.

“At any given point in the winter, we might have 12-14 bodies outside in the snow,” said Amiano. “The shop was a decent size, and we could get five or six cars in there to work on, but we were doing just too many, and then it would be a mad rush to get everything to Gainesville.

“Basically, it was only a couple of guys in the shop, and Bob was very low-key. We knew what the pressure was, the pressure to get the work out, but he never put any on us.

Shop work

“We were a motley crew working out of a building that was basically a cave, and we didn’t have a spray booth,” he remembers. “If we had a car ready for Bob to shoot the color, we would blow the shop out real good, sweep out the best we could, and let the dust settle. Usually, we’d go to the bar for about an hour and a half and then we’d come back and Gerdes would shoot the color. But the rest of us couldn't do anything, couldn't make any dust while he was spraying, so sometimes we worked under very, very crude conditions.

“We were doing Funny Cars with three to five colors — candies, pearls, you know, whatever — for 750 bucks. Then J would come in and do the lettering and striping, airbrush the grille, headlights, taillights, and everything, which generally cost around $130 unless it was gold leaf. Glen came along in a totally different style than Mr. J, who was very freewheeling, because he's a cartoonist. Glen was a technician who copied the work of Nat Quick, who was his idol.”

The vibe

“Glen would sometimes stay in the shop by himself all night. A lot of times we worked all night. It was better for all of us – the humidity was down, static electricity was down. It was just, you know, no interruptions, except sometimes ‘Jungle’ would call on the phone at like three o'clock in the morning from California and play a harmonica and we’d play Name That Tune.

“It was fun because of the people. The work was still work — hard work — but there was a good vibe, and we had good chemistry. When Jay was there, we used to knock off for lunch at about 1 o'clock, and I would go down to the deli and get some bread and cold cuts and stuff. Jay's shop was next door. And we’d go over there and eat lunch and watch The Addams Family on television, you know, just smoke a joint, drink some wine, whatever. I remember one time we were watching The Addams Family and Jay looks at me, and he goes, ‘There's nothing wrong with those people. They're perfectly happy. It's the people around them they can't deal with it.’ We could relate.”

Circus became a popular gathering point for racers to hang out and swap stories, and Gerdes was always in the middle of it, which is why he called Circus “The Entertainment Capital of the World.”

If drivers were in a hurry for their cars, Circus had a “customer participation” allowance. Here “Slamming Sammy” Miller and “Jungle Jim” Liberman are laying out a design on the side of one of Liberman’s cars.

Funny Car driver and acknowledged mafia hitman Freddy DeName was a regular Circus customer who sometimes would leave a “recently appropriated” car on Gerdes doorstep as a thank-you, and life was never dull at Circus.

“Freddy liked us,” reflected Amiano. “I'm sure you've heard all kinds of stories about Freddy. We've never had a problem. Freddy was like a big kid. He would come over from New York with a couple of his buddies and want to know what's going on, you know, get the latest news, and they'd hang out and drink a couple of beers or whatever.

“Back then, before the internet and cell phones and all that stuff, information was very hard to get passed around,” said Amiano. “So, when guys would drop in or call, they’d tell Gerdes their plans, and he’d tell everyone else. He was like the hub, the repository."

When Gerdes moved to upstate New York, many of his clients didn’t want to slog their way through the snow, so, through a mutual introduction by drag racing bon vivant “Berzerko Bob” Doerrer, Gerdes started farming some of the work out to Farmingdale, N.J.-based Jesse Lejeune to keep the business going, and Gerdes eventually moved to Farmingdale himself to continue the Circus legacy. (Doerrer also introduced Gerdes to “Jungle Jim,” for whom Doerrer had worked and traveled in his early Funny Car days). Gerdes and Lejeune later parted company, and Gerdes moved back to New York and did very little work after that due to numerous health issues, but his clientele had grown to include even the stars of the 1980s and ‘90s, like Joe Amato and Frank Manzo, but those 1970s days were the height of the Circus show.

“We caught a window in time that if we had been off by two, three years either way, it wouldn't have happened,” said Amiano, who left in 1978 to go to California to work with Ken Cox. “I’m glad I was able to be a part of it.”

‘Blood work

As talented as Gerdes and crew were, they needed a plan, which often came from artists like famed Kenny Youngblood, whose fertile mind dreamt up the designs that the Circus team had to bring to life.

“It was Camelot!” Youngblood said of that heady era. “I was a talented young artist in love with drag racing, who [by the grace of God] was in the right place [Bellflower, Calif.], at the right time [1969]. I would become the first full-time graphic designer specialized in the realm of motorsports [specifically fuel coupes], during what I would come to know as 'The Great Funny Car Boom of the Seventies.'

“That dream became a reality with the help of five people: custom car painters Dick Olsen, Don Kirby, and Bob Gerdes, Car Craft magazine Editor Terry Cook, and marketing genius Bob Kachler. Olsen, Kirby, and Gerdes provided the arenas wherein I could flex my artistic muscles, while Cook and Kachler were the hawkers.

”I knew who the racers were, but they didn’t know who I was, so Kachler [who knew them all] got the word out via the grapevine, while Cook featured me as a 'High Riser' in Car Craft magazine, as well as showcasing my illustrations [back then, the car magazines were like the TV shows of today].

“By the early ‘70s, I was doing race car paint schemes for clients from coast to coast, as well as an equal if not greater number of sponsorship proposal renderings. This, of course, was 'B.C.' [before computers] when everything was 'analog' [hand drawn]. The only problem was that [with few exceptions] race car painters were not ‘artists’ — they could only do ‘painter tricks’ [like scallops, panels, and flames]. The Funny Cars, however, needed ‘real’ graphic designs and were a much larger canvas than the dragsters, and required professional-looking graphics.

From left, Bob Gerdes, Julian "Mr. J" Braet, Youngblood, and Glen Weisgerber, in a semi-recent photo

“This, of course, required painters capable of accurately laying out those graphics, and applying the right colors — the job would only come out as good as the painter doing it. All too often I would be contacted by a racer wanting a paint scheme [and willing to pay top dollar for its design], who when asked ‘who’s going to paint it?’ they would tell me, ‘My brother-in-law knows a guy who owns a body shop.’ Unfortunately, the results would be predictable.

“And so it was that I came to have a very short list of painters that I would recommend and that I knew could get the job done ‘as designed,’ or better! That list consisted of Don Kirby, Bill Carter, and Tom Stratton on the West Coast, and Bob Gerdes on the East Coast. Bob [with sign artists Glen Weisgerber, Julian Braeburn, and Bert Quimby] would knock it out of the park every time!

"As a designer, it was most rewarding to work with clients who really wanted their cars to be beautiful, racers who wanted to win 'Best Appearing Car' as much [or more] than they wanted to win races! Of those clients were the Castronovo Brothers out of Utica, N.Y. They [along with partners Nick Montana and Angelo Cassaro] wanted their long string of Custom Body Enterprises Funny Cars to be striking. I was honored to be called upon to design most of their Bob Gerdes paint jobs.

“Although it would be years before we would meet in person, Gerdes and I became the best of friends over the phone — he was not only a great painter but a really cool guy. The best part of racing is the people, and Bob was the best of the best!

“I spoke to him not long before he passed, and knew it would probably be our last conversation. For all of us that had the pleasure, thank you Bob, and yes, we’ll ‘see you in the movies!’ “

Thanks to all who shared their memories and photos of Gerdes so that we could give him the kind of sendoff he deserved and add another chapter to the magical history of our sport.

Thanks for all of the well-wishes sent my way via email and Facebook after sharing my tale of recent medical woes. I’m back in the office (still not quite capable of full days yet, but getting close) and, through good days and some that are more challenging, I’m well on the road to recovery and back in the business of telling “the stories behind the stories.”

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator