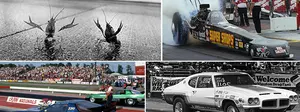

Indy 1971: 'The Great Burndown'

Two weeks ago in Topeka, Pro Stock racers Bruno Massel and Mason McGaha set the internet ablaze with the controversy surrounding their three-and-a-half-minute starting-line staging duel, a battle that neither won after they were both disqualified for refusing to stage.

As cool as that Topeka tempest was, it doesn’t hold a candle to the most famous burndown of all, the starting-line war of wills that took place 50 years ago at the U.S. Nationals between Steve Carbone and “Big Daddy” Don Garlits.

The Massel-McGaha staging skirmish lasted longer, but it was only a first-round race between the No. 8 and 9 qualifiers; the Garlits-Carbone was not just a final-round fight between the No. 1 and 2 qualifiers but also for the most coveted title of any season: Top Fuel in Indy. The stakes just don’t get much higher than that.

THE BUILDUP

As NHRA history fans know (spoiler alert!), Carbone came out the winner when Garlits’ overheated Hemi made a ton more power than the track could handle, and his famed rear-engined Swamp Rat 14 went up in smoke against Carbone’s slingshot.

By all accounts, there wasn’t a lot fueling the fire between Massel and McGaha except maybe pride and stubbornness. The Garlits-Carbone affair was a brewing brouhaha three years in the making, a simmering showdown that was stoked to a fever pitch before the event even began.

Three years earlier on the same battlefield and the same round, Garlits had delayed his staging technique in the final round of the 1968 Nationals. Carbone, at the wheel of Larry Huff's Soapy Sales, had fired and burned out first, and by the time Garlits got Swamp Rat 12-B staged, Carbone’s tires had cooled, his engine had warmed, and Garlits captured his second straight and third overall Indy crown, 6.87 to Carbone's tire-smoking 7.58. Carbone never forgot that moment.

Carbone finally got his first NHRA national event win the next year, and it was a huge one, winning the 1969 NHRA World Finals in Dallas and the world championship that went along with it, a full six years before Garlits would score the first of three NHRA championships. He also won the 1969 AHRA World Finals driving the car owned by Bob Creitz and Ed Donovan, but not the championship.

In 1970, Carbone was a big enough draw to be booked in for a successful series of match races in Australia and also confident enough to go out on his own with a new 392-powered Don Long-chassised car that was decent enough but was getting outrun by cars like Garlits, which had adopted the new 426 Hemi.

THE RIVALRY INTENSIFIES

At an AHRA event at Marion County Int’l Raceway in Marion, Ohio, the week before the 1971 U.S. Nationals, Garlits threw some more salt in Carbone’s wounds when he beat him five times at an AHRA event in Marion. FIVE TIMES? Yep.

That event’s "break rule" allowed the low e.t. loser from the previous round to come back if someone couldn't make the next round and, crazily enough, four times that was Carbone, including the final, where Don Cook broke on his burnout. Carbone was waiting in the wings, stepped in and ran, but lost to Garlits again.

Garlits’ Swamp Rat 14, his revolutionarily successful first rear-engine dragster, had been running 6.30s and even reportedly some 6.20s in testing (and even an unsubstantiated claim of a 6.18) with a new Goodyear tire, clutch, and recently-added rear wing. On the other hand, Carbone was still running the still-prevalent but doomed-to-extinction slingshot design, even after the addition of an Ed Pink-prepped 426.

ON TO INDY

Rumors of Garlits’ 6.2-second testing times quickly became reality in Indy when "Big Daddy" powered to a stunning 6.211 to pace the field, almost two-tenths ahead of Carbone’s second-ranked 6.394. Carl Olson was third with the new rear-engined Kuhl & Olson machine (voted the meet’s Best Appearing Car) with a 6.419 followed by Don Prudhomme’s 6.433 in the now-wedge-less Hot Wheels wedge.

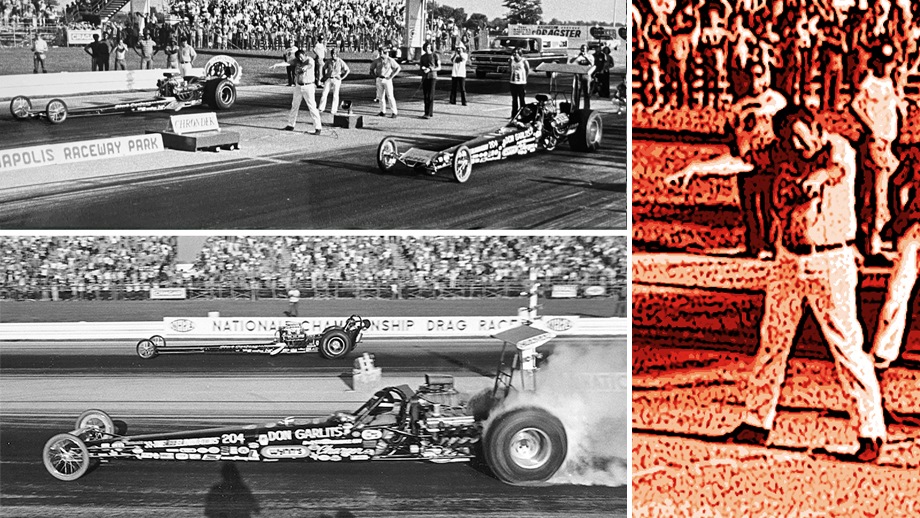

Garlits cruised through the first four rounds of the 32-car field “like a dose of croton oil through a widow woman” (whatever that means; those are Garlits’ own words from his book, Don Garlits and His Cars), beating everyone by at least a tenth (and usually more), setting down the slingshots of Al Friedman (6.28 to 6.65) and John Wiebe (6.32 to 6.46), the Summernationals-winning rear-engine car of Arnie Behling (6.25 to 6.44), and Carl Olson (6.31 to a rear-end-breaking 7.29).

By comparison, Carbone, who was fighting broken rear ends on almost every pass, defeated red-lighting Chuck Kurzawa, Tom Kaiser, Gary Cochran, and Kenny Safford with a best run of 6.39 (against Kaiser’s rear-engined car), so Garlits had him covered by at least a tenth.

SETTING THE STAGE

Carbone knew that he couldn’t outrun the Swamp Rat heads up and was cagey enough to know that while Garlits’ rear-engined machine was the new state-of-the-art, he could turn that against “Big Daddy.”

First, although Garlits was running aluminum heads, which can dissipate heat faster, Carbone’s steel heads would initially be better at absorbing the heat. Second, with the engine behind him, Garlits might not be able to see the heat cooking off the headers, a traditional method for drivers to gauge their engine's health. Third, although both drivers ran water-jacketed heads, Carbone ran a closed system while Garlits had fashioned an overflow tank from an old canteen, meaning that Carbone could monitor the heat on Garlits’ engine in a roundabout manner. And fourth, Garlits’ Swamp Rat was a very light car – just 1,225 pounds – right on the edge of the minimum weight and, according to Garlits, always on the verge of smoking the tires, but the tradeoff was worth it to him as long as he could manage his staging process.

But the biggest ace that Carbone had up his sleeve was Garlits’ ego, that the class’ most popular, successful, and talented driver wouldn’t be cowed into doing something he didn’t want to do.

In a move you’d never see today, Carbone sent word over to Garlits that he would not stage first, setting the trap. Garlits, forever confident in his machinery and the skills of T.C. Lemons, bristled at Carbone’s chutzpah.

"I won't stage first, even if I run out of fuel or the headers melt off the engine," Carbone was reported as stating.

We lost Carbone on Dec. 20, 2005, after suffering a brain aneurysm, so we’re not able to get his side, and I don’t recall seeing an interview with him on the subject, but Olson did direct me to their former crewmember, Don “Fats” Mackay, who was close to Carbone when he drove Kuhl’s car before Olson’s tenure.

“We lost in the semifinals, and Steve’s pit was just two spots over from us,” Mackay said. “I went down there to check on him, and they were replacing a broken rear end, so I helped Danny Porche do that. [Gene’ Mooneyham Jr.] was on the crew then, too.

“Steve was pretty quiet around people not in his circle, but we all knew he was still pretty steamed about what had happened in Ohio because he also felt there had also been some shenanigans going on.

“Steve also lowered the idle so much that the thing would barely run, and would be slower to build heat. You could almost hear every cylinder firing: 1-8-4-3-6-5-7-2.”

PREPARING FOR BATTLE

Garlits, having none of Carbone’s nonsense, threw down the gauntlet not only by firing first, doing his burnout first, and pre-staging first. Carbone was second to light; reports include that because he’d run a lot of water through the block between rounds to extra-cool it, the Hemi had trouble finding fire.

Carbone slowly followed suit and lit his pre-stage bulb. And there they sat for what is estimated to be two and a half minutes, a lifetime for a cackling, nitro-burning engine. As Lemons frantically tried to wave Garlits into stage, Garlits’ engine started to smoke and steam from the canteen. Chief Starter Buster Couch realized the potential peril that literally was brewing and again ordered the drivers to stage and backed the crews and starting-line staff away. Lemons threw up his hands in frustration as if he knew what was coming.

His tires growing colder and engine and clutch hotter by the second, Garlits finally relented and staged. Carbone followed suit. The Tree flashed.

The excess heat in Garlits' engine increased the horsepower by about 100 in his estimation (remember, the engines were only making about 1,500 hp at this time, so that’s a significant increase), and the heated clutch grabbed harder, and the predictable thing happened: Garlits smoked the tires.

Garlits went up in smoke and, to his credit and driving talent, still recovered enough to run 6.55, but Carbone was long gone to a 6.49 pass, with both cars running 229 mph.

Recalled Carbone, "I let the clutch out, and then I didn't see him. I kept waiting to see him, thinking, 'He'll be here any minute.' Then, 'Hmmm, that's the first light; I won this damn thing.' "

‘BIG’ REGRET

Years later, Garlits remarked, “I should have had my head examined, all I had to do was make sure my car was a little warm before going to the line, do the burnout, quickly stage, and Carbone would have had to stage with a cold engine. But I was stupid and had an ego bigger than all outdoors, I went up cold as ice to play the game!

“I don't guess Carbone would have ever staged, the heat in the aluminum head 426 had reached phenomenal temperatures, and this increased the horsepower. The Goodyears couldn't hold the power, and I spun the tires instantly. Steve took an easy ride to his first and only U.S. Nationals win. He was a great guy and deserved to win that event as he was smarter that time. It doesn't pay to play games at national events when you have the upper hand!

"I didn't make the right decision. I'm only human. I should have gone bink-bink and staged, and he wouldn't have known what happened to him. I could have had nine U.S. Nationals championships instead of eight. That's the one race I'd like to do again. But it was my own fault."

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator