Jeff Courtie: A pair of pretty sound careers

|

As a kid gawking at the pit ropes at Southern California dragstrips, all we ever wanted was to be acknowledged by our quarter-mile heroes. A “Hey kid, how ya doing?” or even a “Stop staring at me, will ya?” would have been high-octane stuff for pit rats and track tramps like us. We worshipped these guys who weekend after weekend strapped into colorful, loud, and bitchin’ Funny Cars to burn rubber and haul ass for our enjoyment. (At that young age, I don’t think we yet realized that the drivers were doing it for themselves as much as for us, but we learned.)

Although there were gods among the mere mortal men – giants like Prudhomme and McEwen and Foster with national reps – all of the drivers were heroes in our eyes. It didn’t matter that most of their names were never called out by Steve Evans in his “Be There” radio spots promising a “fiberglass forest” of cars in the pits, guys like Jeff Courtie, Mike Halloran, Jim Terry, Clarence Bailey, Steve Leach, Leon Cain, Bryan Raines, Roger Garten, and dozens more who were there week in and week out to keep “the Snake” honest and to show any out-of-town visitors just how tough SoCal Funny Cars were, and the fans loved them for that.

All of this is a roundabout way of introducing –- and in some cases, reintroducing –- you to Courtie, who dropped me a line and a CD full of images the other day. Even though he wasn’t particularly well-known outside of the West Coast, it was still a great thrill to hear from a guy I’d grown up watching race at places like OCIR and Irwindale and had now (finally!) acknowledged my existence.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

While most fans probably remember Courtie for a string of Mustang and Barracuda Funny Cars that ran on tracks up and down the West Coast from 1971 through 1978, thumping out solid numbers that belied his apparent low-buck stature at places like Lions, OCIR, the Dale, Ontario, Fremont, Seattle, Portland, Pomona, Bakersfield, and Beeline in Arizona, Courtie actually began his quarter-mile career behind the wheel of this cool-looking wood-sided ’48 Oldsmobile station wagon in 1967 at San Fernando Raceway.

"I grew up in North Hollywood, within bicycle distance of [engine builder Dave] Zeuschel’s shop, C&T Strokers, Ed Pink’s, B&M, and Exhibition Engineering ... and those cool places. I was hanging around with Tom Larkin, and Lil' John Lombardo’s dad’s flooring business was not far from where I lived. We’d bicycle up to San Fernando and sometimes sneak in, and all of this was a big influence on me.”

His dad loaned him $200 to buy the Woody, which he had spied parked at a local gas station. A member of the famed Checkers motorcycle club, Courtie initially bought the Woody to transport his motorcycle to the desert, but after seeing Mike Sorokin and the Surfers win the 1966 March Meet, he got the hot rodding bug.

He bought some slicks from Ronnie Winkle and replaced the car’s original straight-eight engine with a 394-cid Olds V-8. Courtie initially ran the car on alcohol but soon added a blower – one that had been backfired on the Top Fuel car of Larry Dixon Sr. – and ultimately the car was powered by a blown and injected nitro-burning 392 Chrysler backed by a B&M Hydro Stick tranny and ran low 10s at 150 mph.

Unfortunately, Courtie’s “Super Woody” was as heavy as it was cool, and, due to its girth and high horsepower, was prone to driveline breakage, so when Funny Cars became the new showstoppers in the early 1970s, Courtie went plastic.

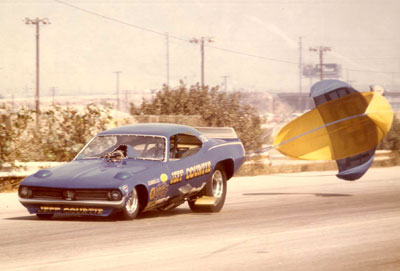

His first Funny Car was a ’70 Mustang with a Logghe-style chassis that he built in his garage and first campaigned in 1971. It, too, was 392-powered and was replaced by a new narrower chassis (in the vein of the radical Mickey Thompson chassis designed by Pat Foster) and fitted with his first Barracuda body, which exited in mid-wheelstand one day at OCIR. Courtie was a tool-and-die apprentice and bounced from machine shop to machine shop, picking up valuable experience and skills.

A newer, lower ‘Cuda body was mounted for the following year, but it, too, met a tragic end. At the 1974 World Finals at Ontario Motor Speedway, both rear axles – which, as it turned out, had been defectively heat-treated -- broke just as Courtie shifted into high gear, launching the blower and the body “into orbit,” as Courtie likes to say.

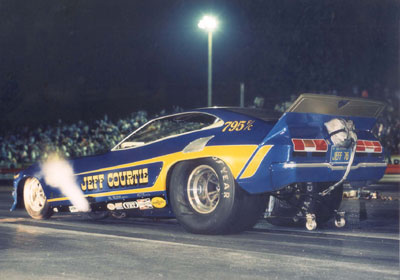

The now-426-powered hot rod went back to its Mustang roots in 1975 with one of the swoopy new Mustang II bodies, which stayed on the car until Courtie hung up his driving gloves in July 1978 and the car was sold to an Australian team. It was a wondrous time, with plentiful racetracks and race dates for gypsy-like processions on the match-race trail up and down the coast, and for many, it was brotherhood of kindred souls.

“Those were good times,” he remembers. “Everyone was kind of equal in that we all only had one of everything – one block, one crank – and it was really satisfying when we did good. There were highs and lows, but it was a lot of fun. We’d run Portland and Seattle back to back and stay at the Thunderbird Hotel right on the Columbia River, and the parking lot would look like the Orange County pits. You’d have ‘Jungle’ and ‘Brutus’ and Gene Snow and Raymond Beadle and Harry Schmidt, 30 or 40 rigs all jammed into the parking lot."

On the match-race circuit, Courtie estimates that he qualified at 90 percent of the races he attended and made it to the semifinals many times. He reached two big final rounds, at Irwindale’s first Oly Grand Premiere in 1973, where he was runner-up to Jim Dunn, and at OCIR’s Nitro Championship in July 1976 for his biggest score, the race win.

“Winning that race was huge,” he recalled. “Beadle was there, Billy Meyer, Lombardo, Snow, all the big guys were there. I don’t know if I ever got the recognition back then that I thought I should have gotten, but I was more into just racing the car and having a nice-looking car. I had a pretty good following; we’d get a lot of people who came by the trailer to wish us well against the big guys.”

Success on the national event trail, however, was much harder to come by.

“I entered almost all of the NHRA West Coast national events, but with the amount of cars back then, sometimes 60 or 70 cars at each event trying for 16 spots, I was unable to qualify at any of those events,” recalled Courtie, who also ventured back East and ran the Springnationals in Ohio in 1973. “I just missed the show at some, and the weather and mechanical gremlin problems [caused me to not qualify] at the others.”

“By the late ‘70s, Beadle and Billy Meyer and guys like that were pulling in with 18-wheelers and had two magnetos and dual fuel pumps and were really mega-dollaring it with spare parts and bigger budgets. I was running it out of my pocket and really struggling. I was getting some product help with oil and gaskets and spark plugs and stuff like that, but you still had to buy the rest of the stuff.”

As expenses increased and his all-volunteer crew grew up and began to get married, start families, and hold “real” jobs, it became harder and harder for Courtie to staff his team, and his own new career – one that took advantage of his race-car-building savvy -- began also to steal time and energy from the race car.

“In 1976, I was offered a job as a fabricator, weldor, and machinist at a company in Burbank [Calif.] that had a fleet of videotape camera trucks,” he said. “At the time, they were the leader in the field of remote videotaping on location for television. My job responsibilities escalated to the point where I became a special projects engineer involved in the design and construction of specialty vehicles. Around this time, the company began building remote trucks for outside customers. We built the first two 40-foot eight-camera trucks for ESPN when they went on the air and helped set up their studios in Bristol, Conn. We built a lot of those 40-foot trucks for different sports-related customers. Demands from that job and the escalating costs of running a Funny Car out of my own pocket forced me to make the painful decision to stop racing.”

|

In 1982, Courtie branched out yet again and became a recording engineer in the company’s television post-production studios. During the next six years, he worked on a lot of successful feature films and episodic television shows. In 1988, he was promoted to ADR/Foley mixer, learning the meticulous dual crafts necessary for today’s productions. (ADR is the process of re-recording dialogue for a film or TV show in the studio – which can amount to as much as 90 percent of the final soundtrack – and Foley is the process of using various implements to create specialized sounds to match the on-screen action, sounds that could not be recorded when the footage was shot, such as footsteps, hand pats, cooking, etc. that usually cannot be found in a sound-effects library.)

In the 20 years since, Courtie has worked on a number of major films and with great actors and actresses, including Paul Newman, Kim Bassinger, Sandra Bullock, Angelina Jolie, Kirk Douglas, Mel Gibson, Raquel Welch, Drew Barrymore, Anthony Hopkins, Dennis Hopper, Morgan Freeman, Richard Dreyfuss, Jack Palance, James Coburn, and many others, and worked, either as an ADR or Foley mixer, on memorable films such as Dead Presidents, Billy Madison, Pulp Fiction, The Cowboy Way, Ed Wood, Bull Durham, and two dozen more (which should make watching the end credits more fun for all of you).

He was nominated for a Emmy for his sound-mixing work on 1989’s The Magic of David Copperfield XI: The Explosive Encounter and has earned four coveted MPSE Golden Reel awards and 13 more Golden Reel nominations for outstanding achievement in sound in the motion-picture and television industries.

Today, he mostly works as a Foley mixer in Burbank, currently working on popular series such as Heroes, Ghost Whisperer, Lipstick Jungle, New Amsterdam, Misguided, and My Boys, as well as a host of upcoming movies.

|

Courtie, now 61, lives in Shadow Hills, Calif., not far from Burbank, with his wife, two teenage daughters, and his beloved ’37 Ford Tudor. When he’s not working or cruising the town in his new hot rod, he’s kept busy renovating his house or camping in the family motorhome. He attends all of the NHRA California Hot Rod Reunions, the March Meet, and both Pomona national events.

And, yes, even almost 30 years after he stopped driving, he still misses racing.

“That was a special time for many of us who were lucky enough to follow our dreams and race against and become friends with some of the greats of the sport,” he says.